Reviewed by Brenda S. Cox

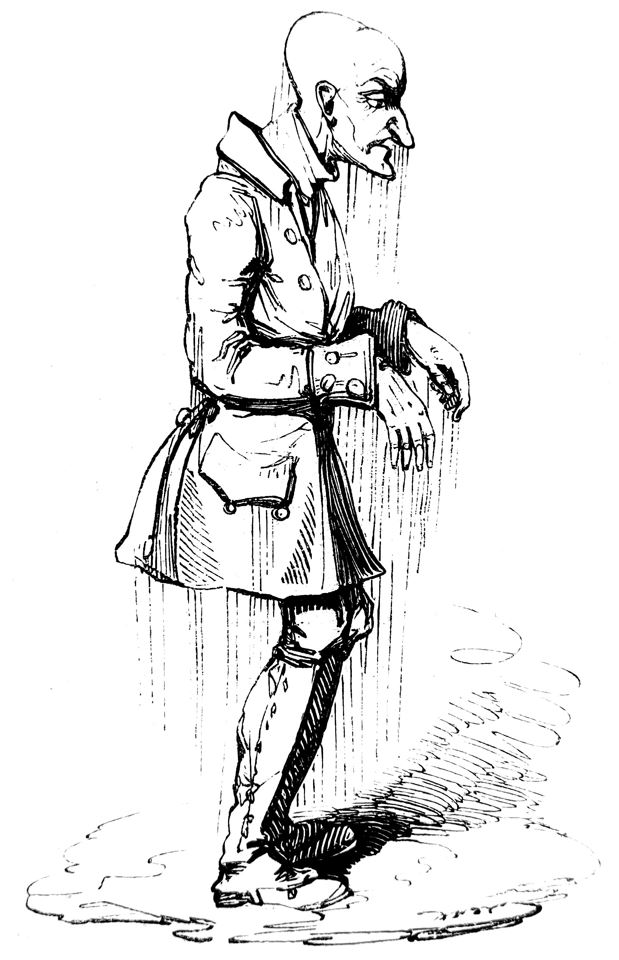

“I have seen nobody in London yet with such a long chin as Dr Syntax” (Jane Austen, March 2, 1814).

I just finished reading, cover to cover, a brand-new book which is over 200 years old. The Tour of Doctor Syntax in Search of the Picturesque, by William Combe, is a classic which Jane Austen herself enjoyed. But it’s out in a new edition, with wonderful illustrations, explanations, and comments.

The story in verse was first published from 1809-1811 as a series in Ackermann’s Poetical Magazine. Ackermann had a series of prints by the great caricaturist Thomas Rowlandson. They featured a country clergyman with a long pointed chin and a tall white wig traveling through the countryside. Ackermann gave Combe the illustrations for each issue of the magazine, and Combe wrote a section of the story to go with them. He didn’t know ahead of time what the pictures would be for the next issue, but somehow he came up with a coherent story. One interesting facet is that Rowlandson apparently intended to satirize the clergy, but Combe made Syntax into a good, learned man, a little silly, but lovable.

A book version came out in 1812. Dr. Syntax was wildly popular and stayed in print, with multiple printings and editions, well into the 1800s.

This new version of The Tour of Doctor Syntax was edited and annotated by an advanced high school class and their professor, Dr. Ben Wiebracht. Ben actually discovered Dr. Syntax through one of my posts right here at Jane Austen’s World. Recognizing its potential for his class on “Jane Austen and Her World,” he asked Vic Sanborn, owner and primary writer of this website, and myself, to share with his class. Vic owns some lovely Rowlandson prints. We both loved connecting with such bright and interested students, who asked knowledgeable questions.

The Book

They’ve done a brilliant job with the book. It starts with a biography of William Combe and the history of the book itself. Combe’s challenges as a writer in Austen’s age were fascinating to me, as a writer myself. A clear introduction explains “the picturesque,” which is mentioned in Austen’s novels. Parallel to the text are straightforward explanations of difficult terms and phrases. That makes them easy to quickly reference. A glossary in the back gives terms previously defined.

The best part, for me, are comments pointing out parallels with Jane Austen’s work. I can’t even begin to list these, but there are many great insights. Some are about the clergy in Austen’s work, since Syntax is an underpaid country curate like Charles Hayter of Persuasion. Many comments have to do with the “picturesque,” “improvement” and country estates ranging from Sotherton to Pemberley. Others relate to the class system, Gothic novels, and other topics.

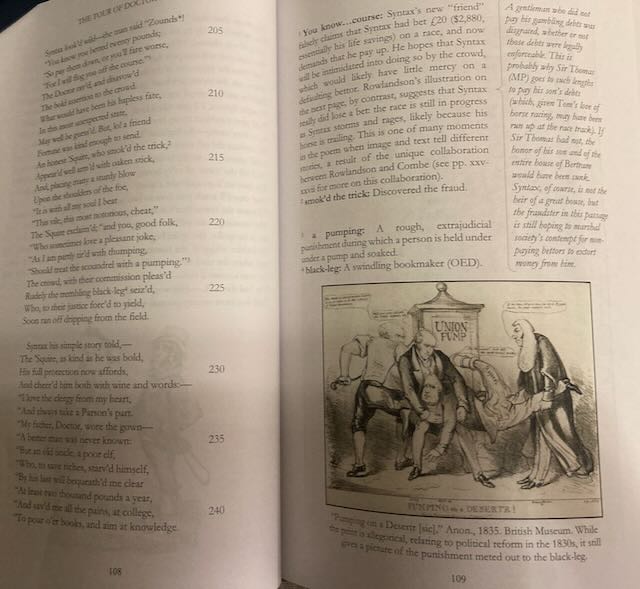

I also loved the illustrations. The editors chose the best versions they could find of each of the full-page, hand-colored pictures by Rowlandson that were the basis of the book. They added illustrations from a later Victorian version, as well as other entertaining and illuminating cartoons and pictures from the time.

Interview with the Editor

I’ll let Dr. Wiebracht himself tell you more about how this book came about.

Ben, please tell me about your class that produced this book.

The class is called “Jane Austen and Her World” and it’s designed for advanced juniors and seniors. The goal is to see Austen’s novels not as sealed-off masterpieces, floating in a historical vacuum, but as windows into her world. Most class days, our Austen reading is accompanied by shorter texts designed to create a sense of context and show how Austen was in conversation with her contemporaries. For instance:

- We pair Austen’s account of Bath in Northanger Abbey with a number of late 18th-c. satires of Bath, 18th-c. dance music, and illustrations of the city by Rowlandson and others.

- We pair Catherine’s pseudo-Gothic adventures in Vol. II with excerpts from The Monk, The Castle of Otranto, and The Mysteries of Udolpho.

- We pair the private theatricals in Mansfield Park with a viewing of a performance of Lover’s Vows, as well as specimens of anti-theatrical criticism from the period, including a satire on private theatricals by Jane’s brothers!

- We pair the discussion of landscape gardening in Mansfield Park with images from Humphry Repton’s famous “red books” showing “before and after” estate grounds.

The idea is to understand Austen in a deeper way by developing the practice of “reading outward.” And we incorporate that principle in our work for the class. Instead of the usual school essays, students work with me to create a critical edition of a neglected text from Austen’s time, with annotations and other resources that draw connections between the text and Austen’s life and work.

The class enrolled 16 students (the maximum). They hailed from all over the country and world: Japan, China, and many different U.S. states. This was my first time teaching the course, though I developed the core ideas in an Austen unit for a previous course. In the future, I will probably teach the course every three years. The book project in particular is a heavy lift, and I’m not capable of it every year!

How did you end up studying Dr. Syntax along with Jane Austen?

I have to back up a bit here. In the course of an Austen unit for a previous class, students and I had created a critical edition of a long-forgotten 1795 poem called Bath: An Adumbration in Rhyme. We used that book to launch a new series called “Forgotten Contemporaries of Jane Austen.” Its goals are:

- to recover neglected but valuable texts from Austen’s time, and

- to trace new connections between Austen and her contemporaries.

As I was preparing my Austen class, I settled on Doctor Syntax (first brought to my attention in JAW by one of your articles!) for three reasons.

- First, the poem had undeniable literary-historical importance – one of the all-out bestsellers of the Regency. A critical edition, I thought, was long overdue.

- Second, many of its themes – from the plight of poor clergy to the “picturesque” – were major concerns of Austen’s novels, too.

- Finally, the poem was simply a really good read. Combe’s verses are light, fun, and at times even touching, and Rowlandson’s accompanying illustrations are some of his best work. In every way, the poem deserved to be revived!

What do you hope readers will gain from the book?

There are a lot of things I hope people take away! One would be a deeper appreciation of just how engaged Austen was in the debates and issues of her day. Sometimes Austen is talked about as something of a provincial writer, sealed off from the wider Regency world, modestly toiling away on her “pictures of domestic life in country villages,” as she once put it. But when we keep in mind just how much of a smash hit Doctor Syntax was, and when we consider the many, many parallels between this work and Austen’s novels, which our edition lays out in detail, then we see Austen differently. She now starts looking like a very savvy writer, who understood what the major issues of the day were, what readers were interested in. To be sure, she stuck to her convictions and drew on her own experience and observations, but she did so in a way designed to appeal to a broad, national readership.

I’m also excited for people to meet this poet William Combe, who had one of the most interesting lives of any Regency writer. He was a remarkable literary talent. He doesn’t fit the mold of the “Romantic poet,” which is one reason he might be overlooked. Instead he offers a light, generous humor that shows us that Regency poetry wasn’t all about Byronic heroes and Wordsworthian dreamers. There was a sociable, comic side to the poetry of the period. Combe represents that comic side particularly well.

Finally, I would love it if this book inspired other teacher-scholars to undertake collaborative research with their students – especially at the upper-high-school level. There are so many benefits. For students, it’s a more rewarding and enjoyable approach to literary scholarship than the usual school essays. For teachers, it’s a welcome relief from the role of “judge/grader” – instead you get to teach through co-creation, as is done in most trades through the apprenticeship model. And for the reading public, there’s the benefit of the work produced! I am convinced that student involvement, with the right guidance and leadership from the teacher, leads to better scholarship. It certainly has in my experience.

By the way, while we don’t offer a Kindle edition, we do offer a free etext in the form of a downloadable PDF on our website. We decided from the beginning to be an open-access publisher, in part to make it easier for teachers with low-income students to assign our books. The best way to use the e-text is to enable the 2-page view in your pdf reader – that way the text and notes are neatly parallel, as in the physical book. The etext can also be used as a supplement to the physical book – for instance if you want to do a text search for a particular word.

How did you and the students share the work on this project?

Each student was responsible to annotate one of the poem’s 26 cantos, about ten pages of text. I did the other ten cantos myself. Students also had one or more additional responsibilities, which included:

- Researching aspects of Combe’s life

- Researching Gilpin and the picturesque

- Compiling chronologies

- Drawing maps

- Designing the cover

- Editing the text according to scholarly standards

My job was twofold. First, I offered regular feedback on work in progress, helping students learn how to navigate library databases, write good, concise annotations, etc. I also did the parts of the book that were a bit beyond the reach of high-school students, even excellent ones, which all the students who worked on this book were! For example, I wrote most of the introductory materials, as well as some of the trickier annotations. I helped with the final prose, too, to ensure continuity of voice. That doesn’t mean, though, that the best stuff is mine. Many of the best, most insightful annotations in the book are entirely by students, and every one of my students has some of their own writing, their own voice in the final book – which was a major priority for me. And just as students benefited from my feedback, I benefitted from theirs. They fully earned their editor credits in the final book.

Final Thoughts

Dr. Wiebracht and his class did an amazing job. I highly recommend this book, which is available on Amazon and from Jane Austen Books at a discount. I have not yet read the earlier book in the series, Bath: An Adumbration in Rhyme, but now I want to get hold of that and read it, too!

If you’re at the JASNA AGM this month, you can hear Ben and some of his students speak, and get them to sign your copy of the book. (Unfortunately I’m speaking in a slot opposite theirs, as well as other excellent speakers at that time, so you’ll have to choose! It’s always challenging.) Their talk is also available in the virtual version of the AGM.

The price is very reasonable for a book with color illustrations. I hope you’ll get a chance to enjoy and learn from this lovely book!