Having just made a big move myself, I was intrigued by the thought that Jane Austen herself—not to mention several of her characters—knew what it took to move an entire household from one place to another.

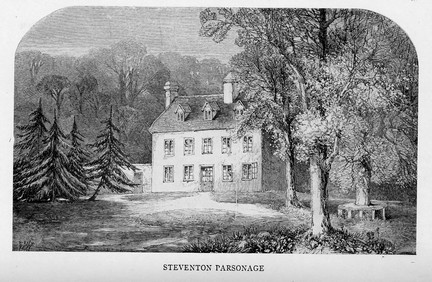

One of the best resources available to us regarding a big move is the letter Austen wrote to Cassandra on January 3, 1801, prior to their family’s move to Bath from Steventon. From it, and from the details in her novels, we learn many interesting details about what a big move entailed.

If you’ve ever wanted some Regency advice on moving house, this is for you!

Send Your Servants Ahead

In terms of logistics, members of the genteel class usually sent servants ahead of them when they went from one house to another, as we see when Mr. Bingley goes to Netherfield:

Why, my dear, you must know, Mrs. Long says that Netherfield is taken by a young man of large fortune from the north of England; that he came down on Monday in a chaise and four to see the place, and was so much delighted with it that he agreed with Mr. Morris immediately; that he is to take possession before Michaelmas, and some of his servants are to be in the house by the end of next week.

Pride and Prejudice

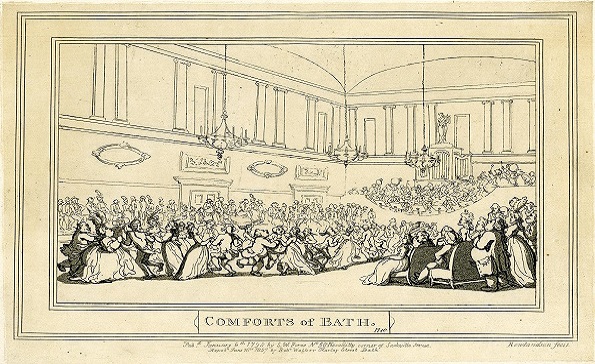

Similarly, Elinor and Marianne, when arriving in London with Mrs. Jennings after three days of travel, are greeted by “all the luxury of a good fire.” The house is “handsome, and handsomely fitted up.” Elinor writes to her mother before a dinner that will not “be ready in less than two hours from their arrival.” It’s clear that Mrs. Jennings employs servants who clean, cook, shop, and prepare the house for her visits.

Hire Good People

When preparing to move to Bath, Jane Austen’s mother wanted to keep two maids: “My mother looks forward with as much certainty as you can do to our keeping two maids; my father is the only one not in the secret.”

With her typical flair for humor, Austen hoped to engage other servants as well: “We plan having a steady cook and a young, giddy housemaid, with a sedate, middle-aged man, who is to undertake the double office of husband to the former and sweetheart to the latter. No children, of course, to be allowed on either side.”

Do Your Research

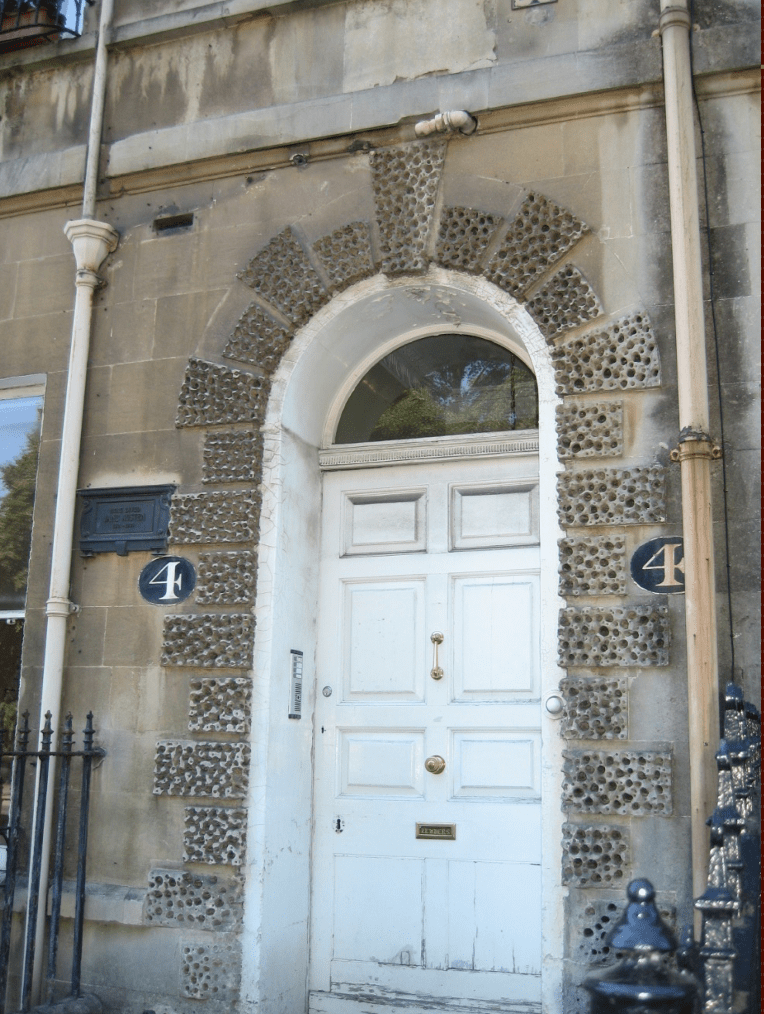

In Austen’s letter, she talks about several areas of Bath where they hoped to find a house: Westgate Buildings, Charles Street, and “some of the short streets leading from Laura Place or Pulteney Street.”

About Westgate Buildings, Austen wrote: “though quite in the lower part of the town, are not badly situated themselves. The street is broad, and has rather a good appearance.” Regarding Charles Street, she thought it “preferable”: “The buildings are new, and its nearness to Kingsmead Fields would be a pleasant circumstance.” And concerning the third area: “The houses in the streets near Laura Place I should expect to be above our price. Gay Street would be too high, except only the lower house on the left-hand side as you ascend.”

Mrs. Austen seemed to have a preference: “her wishes are at present fixed on the corner house in Chapel Row, which opens into Prince’s Street. Her knowledge of it, however, is confined only to the outside, and therefore she is equally uncertain of its being really desirable as of its being to be had.”

None of the Austens were in favor of Oxford Buildings: “we all unite in particular dislike of that part of the town, and therefore hope to escape.”

Bring Your Art

We know from Austen’s letter that they planned to take the following pictures and paintings from Steventon to Bath: “[T]he battle-piece, Mr. Nibbs, Sir William East, and all the old heterogeneous miscellany, manuscript, Scriptural pieces dispersed over the house, are to be given to James.”

Of special note, Jane tells Cassandra, “Your own drawings will not cease to be your own, and the two paintings on tin will be at your disposal.”

Good Furniture is Worth Moving

Apparently, Rev. and Mrs. Austen had a very good bed that was irreplaceable: “My father and mother, wisely aware of the difficulty of finding in all Bath such a bed as their own, have resolved on taking it with them…” Austen wrote this about the rest of the household beds: “all the beds, indeed, that we shall want are to be removed — viz., besides theirs, our own two, the best for a spare one, and two for servants; and these necessary articles will probably be the only material ones that it would answer to send down.”

When it came to their dressers, they decided it was time for an upgrade: “I do not think it will be worth while to remove any of our chests of drawers; we shall be able to get some of a much more commodious sort, made of deal, and painted to look very neat…”

As to the rest of their furniture, they decided it would be better to replace most of it in Bath: “We have thought at times of removing the sideboard, or a Pembroke table, or some other piece of furniture, but, upon the whole, it has ended in thinking that the trouble and risk of the removal would be more than the advantage of having them at a place where everything may be purchased. Pray send your opinion.”

Jane’s final comments to Cassandra are amusing as ever: “My mother bargains for having no trouble at all in furnishing our house in Bath, and I have engaged for your willingly undertaking to do it all.”

Visit People on the Way

In Austen’s letter, she explains their family travel plans: “[M]y mother and our two selves are to travel down together, and my father follow us afterwards in about a fortnight or three weeks. We have promised to spend a couple of days at Ibthorp in our way. We must all meet at Bath, you know, before we set out for the sea, and, everything considered, I think the first plan as good as any.”

Not So Different

Moving house in Jane Austen’s day was not quite so different from today. Though the modes of transportation and the methods of research and communication were somewhat different, I was delighted to find that the Austens’ moving plans were surprisingly applicable to mine! (Except for the servants.)

RACHEL DODGE teaches college English classes, gives talks at libraries, teas, and book clubs, and writes for Jane Austen’s World blog. She is the bestselling author of The Little Women Devotional, The Anne of Green Gables Devotional and Praying with Jane: 31 Days Through the Prayers of Jane Austen. Coming this fall: The Secret Garden Devotional. You can visit Rachel online at www.RachelDodge.com.