Miss Emma Woodhouse was a bright, articulate, privileged and beautiful young lady who possessed an unswerving sense of her lofty position in Highbury society. To some, Gwynneth Paltrow, an equally privileged woman in real life, was perfect for the role. For me, Kate Beckinsale (A&E Emma) and Alicia Silverstone (Clueless) are unbeatable as Jane Austen’s favorite heroine. With PBS’s recent showing of Emma 2009, many are coming to prefer Romola Garai’s more vivacious interpretation. (Read my review here.) Regardless of which actress portrays Emma, class distinctions play a pivotal role in the plot . Today I present to you (largely in Jane Austen’s own words) the reasons why so much ado was made over who could marry whom and why a very young, single woman was given the best seat at Highbury’s tables.

Mr. Elton was presumptuous in courting Emma:

Mr. Elton’s wanting to pay his addresses to her had sunk him in her opinion. His professions and his proposals did him no service. She thought nothing of his attachment, and was insulted by his hopes. He wanted to marry well, and having the arrogance to raise his eyes to her, pretended to be in love; but she was perfectly easy as to his not suffering any disappointment that need be cared for. There had been no real affection either in his language or manners. Sighs and fine words had been given in abundance; but she could hardly devise any set of expressions, or fancy any tone of voice, less allied with real love. She need not trouble herself to pity him. He only wanted to aggrandise and enrich himself; and if Miss Woodhouse of Hartfield, the heiress of thirty thousand pounds, were not quite so easily obtained as he had fancied, he would soon try for Miss Somebody else with twenty, or with ten…”

Mr Elton presumes to sit between Emma and Mrs. Weston

Perhaps it was not fair to expect him to feel how very much he was her inferior in talent, and all the elegancies of mind. The very want of such equality might prevent his perception of it; but he must know that in fortune and consequence she was greatly his superior. He must know that the Woodhouses had been settled for several generations at Hartfield, the younger branch of a very ancient family–and that the Eltons were nobody. The landed property of Hartfield certainly was inconsiderable, being but a sort of notch in the Donwell Abbey estate, to which all the rest of Highbury belonged; but their fortune, from other sources, was such as to make them scarcely secondary to Donwell Abbey itself, in every other kind of consequence; and the Woodhouses had long held a high place in the consideration of the neighbourhood which Mr. Elton had first entered not two years ago, to make his way as he could, without any alliances but in trade, or any thing to recommend him to notice but his situation and his civility. – Chapter 16

Donwell Abbey

When a woman married, she took on her husband’s status. Therefore it would have made no sense for Emma to have come down in the world and married Mr. Elton, a mere vicar. For marriage material, she (and her sister) would have naturally looked towards the Knightley brothers. Be that as it may, Emma thought of Mr Elton as “quite the gentleman himself, and without low connections; at the same time not of any family that could fairly object to the doubtful birth of Harriet. He had a comfortable home for her, and Emma imagined a very sufficient income; for though the vicarage of Highbury was not large, he was known to have some independent property;” (I, Ch.4, p.33) After Emma’s unceremonious rejection of his suit, Mr. Elton left Highbury in a dudgeon and wound up marrying well, for his bride came with £10,000.

The charming Augusta Hawkins, in addition to all the usual advantages of perfect beauty and merit, was in possession of an independent fortune, of so many thousands as would always be called ten; a point of some dignity, as well as some convenience: the story told well; he had not thrown himself away—he had gained a woman of 10,000, or thereabouts; and he had gained her with such delightful rapidity—the first hour of introduction had been so very soon followed by distinguishing notice; the history which he had to give Mrs. Cole of the rise and progress of the affair was so glorious—the steps so quick, from the accidental rencontre, to the dinner at Mr. Green’s, and the party at Mrs. Brown’s—smiles and blushes rising in importance—with consciousness and agitation richly scattered—the lady had been so easily impressed—so sweetly disposed—had in short, to use a most intelligible phrase, been so very ready to have him, that vanity and prudence were equally contented.

Blake Ritson and Christina Cole as Mr and Mrs. Elton

Mr. Elton provided his wife with a respectable home and living. Augusta’s mistake was in thinking that through her marriage, she belonged to the same echelon of society as Emma. In Emma’s estimation:

[Mrs. Elton] was good enough for Mr. Elton, no doubt; accomplished enough for Highbury—handsome enough—to look plain, probably, by Harriet’s side. As to connection, there Emma was perfectly easy; persuaded, that after all his own vaunted claims and disdain of Harriet, he had done nothing. On that article, truth seemed attainable. What she was, must be uncertain; but who she was, might be found out; and setting aside the 10,000l., it did not appear that she was at all Harriet’s superior. She brought no name, no blood, no alliance. Miss Hawkins was the youngest of the two daughters of a Bristol-merchant, of course, he must be called; but, as the whole of the profits of his mercantile life appeared so very moderate, it was not unfair to guess the dignity of his line of trade had been very moderate also. Part of every winter she had been used to spend in Bath; but Bristol was her home, the very heart of Bristol; for though the father and mother had died some years ago, an uncle remained—in the law line—nothing more distinctly honourable was hazarded of him, than that he was in the law line; and with him the daughter had lived. Emma guessed him to be the drudge of some attorney, and too stupid to rise. And all the grandeur of the connection seemed dependent on the elder sister, who was very well married, to a gentleman in a great way, near Bristol, who kept two carriages! That was the wind-up of the history; that was the glory of Miss Hawkins.

Hartfield

The Coles, who made their living from trade, did not move in the same circles as Emma, but many of the people she associated with felt comfortable visiting the Coles, including the Westons and Mr. Knightley:

The Coles had been settled some years in Highbury, and were very good sort of people–friendly, liberal, and unpretending; but, on the other hand, they were of low origin, in trade, and only moderately genteel. On their first coming into the country, they had lived in proportion to their income, quietly, keeping little company, and that little unexpensively; but the last year or two had brought them a considerable increase of means– the house in town had yielded greater profits, and fortune in general had smiled on them. With their wealth, their views increased; their want of a larger house, their inclination for more company. They added to their house, to their number of servants, to their expenses of every sort; and by this time were, in fortune and style of living, second only to the family at Hartfield. Their love of society, and their new dining-room, prepared every body for their keeping dinner-company; and a few parties, chiefly among the single men, had already taken place. The regular and best families Emma could hardly suppose they would presume to invite– neither Donwell, nor Hartfield, nor Randalls. Nothing should tempt her to go, if they did; and she regretted that her father’s known habits would be giving her refusal less meaning than she could wish. The Coles were very respectable in their way, but they ought to be taught that it was not for them to arrange the terms on which the superior families would visit them. This lesson, she very much feared, they would receive only from herself; she had little hope of Mr. Knightley, none of Mr. Weston.

But she had made up her mind how to meet this presumption so many weeks before it appeared, that when the insult came at last, it found her very differently affected. Donwell and Randalls had received their invitation, and none had come for her father and herself.

Mr. Robert Martin, yeoman farmer, made a comfortable living, but he had no social standing to speak of, at least not in Emma’s eyes:

Jefferson Hall as Robert Martin

There was no reason for Emma to associate with a young yeoman farmer and she was not expected to acknowledge him when they met in public, for they had not formally met. And he would not presume to speak to her until he received a proper introduction. This conversation between Emma and Harriet explains Emma’s attitude towards Mr. Martin:

Harriet: But, did you never see him? He is in Highbury every now and then, and he is sure to ride through every week in his way to Kingston. He has passed you very often.”

Emma: “That may be—and I may have seen him fifty times, but without having any idea of his name. A young farmer, whether on horseback or on foot, is the very last sort of person to raise my curiosity. The yeomanry are precisely the order of people with whom I feel I can have nothing to do. A degree or two lower, and a creditable appearance might interest me; I might hope to be useful to their families in some way or other. But a farmer can need none of my help, and is therefore in one sense as much above my notice as in every other he is below it.”

The success of tradesmen and farmers meant the class distinctions were beginning to blur at this time: “Mr. Martin is not, in fact, a mere tenant “farmer” but a prosperous yeoman – an excellent catch for the portionless Harriet Smith.” (- Cathleen Meyers, Emma). In fact, Harriet recalls her two months with the Martins with fondness:

… she had spent two very happy months with [the Martins], and now loved to talk of the pleasures of her visit, and describe the many comforts and wonders of the place … of Mrs. Martin’s having “two parlours, two very good parlours indeed; one of them quite as large as Mrs. Goddard’s drawing-room; and of her having an upper maid who had lived five-and-twenty years with her; and of their having eight cows, two of them Alderneys, and one a little Welch cow, a very pretty little Welch cow, indeed; and of Mrs. Martin’s saying, as she was so fond of it, it should be called her cow; and of their having a very handsome summer-house in their garden, where some day next year they were all to drink tea:—a very handsome summer-house, large enough to hold a dozen people.”

Mr. Martin worked on Mr. Knightley’s estate, and the two men saw each other frequently to conduct business, which is how Mr. Knightley came to greatly esteem the sensible young man:

I never hear better sense from any one than Robert Martin. He always speaks to the purpose; open, straight forward, and very well judging. He told me every thing; his circumstances and plans, and what they all proposed doing in the event of his marriage. He is an excellent young man, both as son and brother. I had no hesitation in advising him to marry. He proved to me that he could afford it; and that being the case, I was convinced he could not do better. I praised the fair lady too, and altogether sent him away very happy.

Once Harriet married Robert Martin, she and Emma would no longer travel in the same social circles. But, as Mr. Knightley rightly pointed out, Mr. Martin was an excellent catch for Harriet, the natural daughter of somebody. When Mr. Knightley learns that Harriet (through Emma’s persuasion) had rejected Mr. Martin’s proposal of marriage, he exclaimed:

Louise Dyland as Harriet and Romola Garai as Emma read a riddle

“No, he is not her equal indeed, for he is as much her superior in sense as in situation. Emma, your infatuation about that girl blinds you. What are Harriet Smith’s claims, either of birth, nature or education, to any connection higher than Robert Martin? She is the natural daughter of nobody knows whom, with probably no settled provision at all, and certainly no respectable relations. She is known only as parlour-boarder at a common school. She is not a sensible girl, nor a girl of any information. She has been taught nothing useful, and is too young and too simple to have acquired any thing herself. At her age she can have no experience, and with her little wit, is not very likely ever to have any that can avail her. She is pretty, and she is good tempered, and that is all. My only scruple in advising the match was on his account, as being beneath his deserts, and a bad connexion for him. I felt, that as to fortune, in all probability he might do much better; and that as to a rational companion or useful helpmate, he could not do worse. But I could not reason so to a man in love, and was willing to trust to there being no harm in her, to her having that sort of disposition, which, in good hands, like his, might be easily led aright and turn out very well. The advantage of the match I felt to be all on her side; and had not the smallest doubt (nor have I now) that there would be a general cry-out upon her extreme good luck.

Miss Bates and Mrs. Bates, although well respected, had no money to speak of:

Tamsin Greig as Miss Bates

The penniless widows of Vicars led a hard-scrabble life, for there were no pensions. As a former Vicar’s wife, Mrs. Bates still had some social standing in the community, retaining her position in the second tier of society. But she and her daughter needed to live economically and they depended on charity from friends to help stretch their meager income. After moving from the comfortable vicarage house, they settled into spare rooms above a shop in the center of town.

After these came a second set; among the most come-at-able of whom were Mrs. and Miss Bates and Mrs. Goddard, three ladies almost always at the service of an invitation from Hartfield, and who were fetched and carried home so often that Mr. Woodhouse thought it no hardship for either James or the horses. Had it taken place only once a year, it would have been a grievance.

Mrs. Bates, the widow of a former vicar of Highbury, was a very old lady, almost past every thing but tea and quadrille. She lived with her single daughter in a very small way, and was considered with all the regard and respect which a harmless old lady, under such untoward circumstances, can excite. Her daughter enjoyed a most uncommon degree of popularity for a woman neither young, handsome, rich, nor married. Miss Bates stood in the very worst predicament in the world for having much of the public favour; and she had no intellectual superiority to make atonement to herself, or frighten those who might hate her, into outward respect. She had never boasted either beauty or cleverness. Her youth had passed without distinction, and her middle of life was devoted to the care of a failing mother, and the endeavour to make a small income go as far as possible.

Mr. Weston’s social position was inferior to his son, Frank’s:

Robert Bathurst as Mr. Weston

Mr. Weston, a former military man, married up. His first wife assumed his social standing and came down in the world. This brought conflict to their short marriage. After the first Mrs. Weston died, her son, Frank, was raised by his rich uncle and his wife, the Churchills. It was quite common at the time for childless families to adopt someone else’s child (this happened with Jane Austen’s brother, Edward, who took on the name of his adopted family – Knight), and thus Frank’s social position rose above his father’s. It was not inconceivable or far fetched that Emma would set her eyes in his direction. The adoption meant that Frank was in line to inherit Enscombe, which meant that his most pressing duty lay towards the ailing Mrs. Churchill, who was in control of Frank’s purse strings and her will. Had Mrs. Churchill known of Frank’s secret engagement to Jane Fairfax, a woman with no marriage portion or prospects, she would have been seriously displeased.

Mr. Weston was a native of Highbury, and born of a respectable family, which for the last two or three generations had been rising into gentility and property. He had received a good education, but on succeeding early in life to a small independence, had become indisposed for any of the more homely pursuits in which his brothers were engaged; and had satisfied an active, cheerful mind and social temper by entering into the militia of his county, then embodied.

Captain Weston was a general favourite; and when the chances of his military life had introduced him to Miss Churchill, of a great Yorkshire family, and Miss Churchill fell in love with him, nobody was surprized except her brother and his wife, who had never seen him, and who were full of pride and importance, which the connection would offend.

Miss Churchill, however, being of age, and with the full command of her fortune—though her fortune bore no proportion to the family-estate—was not to be dissuaded from the marriage, and it took place to the infinite mortification of Mr. and Mrs. Churchill, who threw her off with due decorum. It was an unsuitable connection, and did not produce much happiness. Mrs. Weston ought to have found more in it, for she had a husband whose warm heart and sweet temper made him think every thing due to her in return for the great goodness of being in love with him; but though she had one sort of spirit, she had not the best. She had resolution enough to pursue her own will in spite of her brother, but not enough to refrain from unreasonable regrets at that brother’s unreasonable anger, nor from missing the luxuries of her former home. They lived beyond their income, but still it was nothing in comparison of Enscombe: she did not cease to love her husband, but she wanted at once to be the wife of Captain Weston, and Miss Churchill of Enscombe.

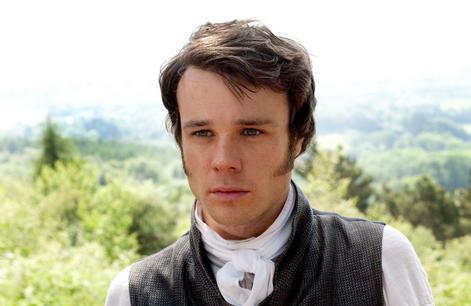

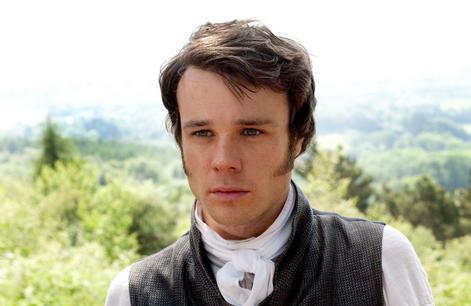

Rupert Evans as Frank Churchill

Captain Weston, who had been considered, especially by the Churchills, as making such an amazing match, was proved to have much the worst of the bargain; for when his wife died, after a three years’ marriage, he was rather a poorer man than at first, and with a child to maintain. From the expense of the child, however, he was soon relieved. The boy had, with the additional softening claim of a lingering illness of his mother’s, been the means of a sort of reconciliation; and Mr. and Mrs. Churchill, having no children of their own, nor any other young creature of equal kindred to care for, offered to take the whole charge of the little Frank soon after her decease. Some scruples and some reluctance the widower-father may be supposed to have felt; but as they were overcome by other considerations, the child was given up to the care and the wealth of the Churchills, and he had only his own comfort to seek and his own situation to improve as he could.

A complete change of life became desirable. He quitted the militia and engaged in trade, having brothers already established in a good way in London, which afforded him a favourable opening. It was a concern which brought just employment enough. He had still a small house in Highbury, where most of his leisure days were spent; and between useful occupation and the pleasures of society, the next eighteen or twenty years of his life passed cheerfully away. He had, by that time, realized an easy competence—enough to secure the purchase of a little estate adjoining Highbury, which he had always longed for—enough to marry a woman as portionless even as Miss Taylor, and to live according to the wishes of his own friendly and social disposition.

Jane Fairfax’s future as governess was tenuous at best:

Laura Pyper as Jane Fairfax

Well educated and raised in comfort by the Campbell’s, Jane’s only hope of making her way in the world was as a governess. Her position in society would have been untenable, as Jane Austen described: “With the fortitude of a devoted novitiate, she had resolved at one-and-twenty to complete the sacrifice and retire from all the pleasures of life, of rational intercourse, equal society, peace, and hope, to penance and mortification forever.” Read more about the position of governess in my post, The Governess in the Age of Jane Austen at this link. The following conversation between Mrs. Elton and Jane describes her predicament:

“I did not mean, I was not thinking of the slave-trade,” replied Jane; “governess-trade, I assure you, was all that I had in view; widely different certainly as to the guilt of those who carry it on; but as to the greater misery of the victims, I do not know where it lies. But I only mean to say that there are advertising offices, and that by applying to them I should have no doubt of very soon meeting with something that would do.”

“Something that would do!” repeated Mrs. Elton. “Aye, that may suit your humble ideas of yourself;—I know what a modest creature you are; but it will not satisfy your friends to have you taking up with any thing that may offer, any inferior, commonplace situation, in a family not moving in a certain circle, or able to command the elegancies of life.”

“You are very obliging; but as to all that, I am very indifferent; it would be no object to me to be with the rich; my mortifications, I think, would only be the greater; I should suffer more from comparison. A gentleman’s family is all that I should condition for.”

“I know you, I know you; you would take up with any thing; but I shall be a little more nice, and I am sure the good Campbells will be quite on my side; with your superior talents, you have a right to move in the first circle. Your musical knowledge alone would entitle you to name your own terms, have as many rooms as you like, and mix in the family as much as you chose;—that is—I do not know—if you knew the harp, you might do all that, I am very sure; but you sing as well as play;—yes, I really believe you might, even without the harp, stipulate for what you chose;—and you must and shall be delightfully, honourably and comfortably settled before the Campbells or I have any rest.”

“You may well class the delight, the honour, and the comfort of such a situation together,” said Jane, “they are pretty sure to be equal; however, I am very serious in not wishing any thing to be attempted at present for me. I am exceedingly obliged to you, Mrs. Elton, I am obliged to any body who feels for me, but I am quite serious in wishing nothing to be done till the summer.

Romola Garai and Jonny Lee Miller as Emma and Mr. Knightley

Highbury was a small, circumscribed town, and Emma’s choices for a mate were extremely limited. It is with no wonder (and quite a bit of satisfaction) that she came to recognize her feelings for Mr. Knightley. With her marriage to him and his willingness to move to Hartfield, her social situation scarcely changed at all.

Additional Resources

Read Full Post »

I know I am late in reviewing this Jane Austen undead novel, which came out in August. My initial reaction to Emma and the Vampires was “Meh!” and “Oh, no, not another one of those deadfuls.” But as I read Wayne Josephson’s book further, its sweet and gentle quality and its quiet humor began to grow on me. Then I became confused.

I know I am late in reviewing this Jane Austen undead novel, which came out in August. My initial reaction to Emma and the Vampires was “Meh!” and “Oh, no, not another one of those deadfuls.” But as I read Wayne Josephson’s book further, its sweet and gentle quality and its quiet humor began to grow on me. Then I became confused. I enjoyed this novel for what it was. This book certainly has a different take on vampires. If it is true that it is geared toward a younger audience, then it has found its niche. While it would not appeal to die-hard fans of True Blood and Ann Rice novels, it does have a charm of its own.

I enjoyed this novel for what it was. This book certainly has a different take on vampires. If it is true that it is geared toward a younger audience, then it has found its niche. While it would not appeal to die-hard fans of True Blood and Ann Rice novels, it does have a charm of its own.