Inquiring readers: Once again, Tony Grant, who lives in London, has written his unique insights about historical events in that great city. This week he concentrates on John Murray, the publisher of four of Jane Austen’s six completed novels. Tony’s contributions to this blog are unique in that he includes his photographs of modern London and mingles them with more traditional illustrations. Read Tony’s blog, London Calling, at this link.

Image @Wikimedia Commons

John Murray

Bookseller and Publisher

Born 1st January 1737

Died 6th November 1793

Lived and conducted business here.

1768 – 1793

On Tuesday 13th March, my son Sam and I had a day out in central London. My brother Michael, who lives in Grenaa on Jutland, is over here with thirty students. Michael teaches mathematics in a further education college in Grenaa. He has lived in Denmark for over thirty years. A couple of weeks ago he phoned me and asked if I could do a Dickens tour of London for his students. On Tuesday Sam and I walked the route I will take Michael’s students. A Dickens walk is difficult. There are so many places in London that have strong links with Dickens.

It is more about what to leave out than what to include. Connecting them all in a walk that will take just over an hour would be impossible. I looked carefully at a map of London to see what places could be linked most appropriately. I think I have chosen a rout that includes many of the main sites connected with Dickens working life in London. I have decided to begin at Hungerford Bridge the site of Hungerford Steps and Warren’s Blacking Factory where Charles Dickens worked as a young child sticking labels on bottles of black polish.

The walk will be along The Strand, past The Adelphi Theatre, to Wellington Street, the Lyric Theatre and then on to Covent Garden before walking on to The Old Curiosity Shop, Lincolns Inn , Chancery Lane, Holborn High Street, past Grays Inn and finally ending at 48 Doughty Street, one of the houses Dicken’s lived in and now The Dickens Museum. Sam and I felt very pleased with ourselves. The walk flowed nicely, punctuated with plenty of Dicken’s sites and the timing was about right. We retraced ours steps, this time continuing down Chancery Lane to the Strand and turning left until we got to Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese, in Fleet Street.

Fleet Street and The Royal Courts of Justice. Image @Tony Grant

Dickens, some of his characters and many other writers and famous people have graced these premises. After a pub lunch in the cellared depths of this ancient establishment we tracked back along Fleet Street towards The Royal Courts of Justice. I just happened to glimpse a small plaque attached to a pillar to one side of a narrow alleyway leading to a small courtyard behind. It read:

Image @Tony Grant

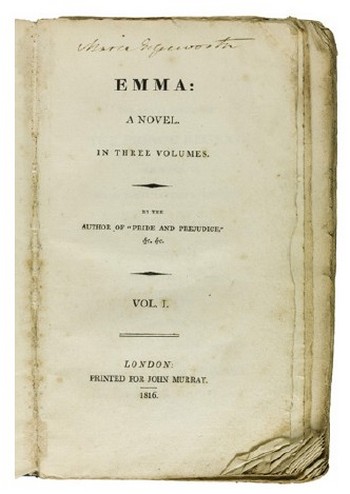

I stopped in my tracks. I thought this must be Jane Austen’s publisher. However the dates did not tally. Jane’s first novel, published by John Murray, was Emma in 1815, long after the final date of death on the plaque. I took photographs of the plaque and courtyard at the end of the alleyway and pictures of Fleet Street, running along outside. When I got home I researched John Murray and found the John Murray publishing firm website.

THIS IS A SHORT HISTORY OF THE PUBLISHING FIRM OF JOHN MURRAY.

The first John Murray, who lived from 1737 to 1793, started his working life as a Lieutenant in the Marines. Life as a marine officer in the 18th century was spent on board naval men of war and consisted of travelling the world to defend the British Empire. It wasn’t a particularly well paid or thought of profession. In Mansfield Park , Fanny’s mother, Frances , the younger Ward sister,

…….married, in the common phrase, to disoblige her family, and by fixing on a Lieutenant of Marines, without education, fortune, or connections, did it very thoroughly.”

John Murray must have had a natural inclination towards business and when he acquired a publishing and bookselling business in Fleet Street in 1768 he made it into a successful business now passed down through the generations. The fact that he acquired a publishing business must mean that it was left to him, perhaps in a will. As a lieutenant of marines it is doubtful he would have had the finances to buy it and it seems a strange choice of business for somebody with his background. He must have acquired it through inheritance and an accident of fate.

The John Murray office was in Falcon Court. Image @Tony Grant

As an indication of his business acumen he was one of the first publishers to actually consider the quality of the writing he published. He also used his many contacts to help sell large quantities of his books. He was a canny businessman though and hedged his bets by also selling game, which would have included deer, pheasants and rabbits; the produce of country sports. He had a go at selling paste jewels and lottery tickets too.

John Murray (or MacMurray, as the name was originally spelt), having bought the stock and goodwill of William Sandley, who had turned banker, began at the ‘Falcon,’ otherwise No. 32 Fleet Street, that remarkable and prosperous career which has culminated in the great publishing house of Murray. In Smiles’ book on the Murrays will be found an exhaustive account of the inception, by Lieutenant MacMurray, of this great firm. – Fleet Street and the Press

Image @Tony Grant

He was astute enough to go with what was most profitable. Books worked for him though. I suppose if the selling of game, he was virtually a butcher as well as a bookseller, paste jewellery or the selling of lottery tickets had provided more income for him the publishing side may well have not contiued and Jane would not have had her publisher in the next John Murray but may well have been buying venison from him instead.

Image @Tony Grant

John Murray II. Image @Austenonly. (Published with permission from Julie Wakefield.)

John Murray’s son John Murray II began to develop the business. He was successful at signing Walter Scott who helped him, among others, such as the secretaries of the admiralty, John Wilson Croker and Sir John Barrow and writers such as Robert Southey and Charles Lamb to publish The Quarterly Review. This journal continued until 1967. In 2007 it was revived. The concept behind it is

to draw upon a wide range of opinions to provide counter-intuitive writing for people who like to think, and to enhance literary, philosophical and political debate.”

50 Albemarle Street. Image @Tony Grant

In it’s early years it tried to counter social reforms. It was rather conservative in it’s views but it did back the abolition of slavery although advocating a slow approach to the process.

50 Albemarle Street. Image @Tony Grant

In 1812, John Murray II published Childe Harold by Byron and it was a great success. This gave Murray the confidence to mortgage some of his copyrights and purchase 50 Albemarle Street, which has remained the home of the publishing firm for the last two hundred years.

Albemarle Street. Image @Tony Grant

The drawing room in Albemarle Street has been the meeting place for some of the most famous writers in English history. By 1815, and after the Battle of Waterloo, everybody wanted to be published by John Murray. It seems therefore that Henry Austen, Jane’s banker brother, must have had no little influence in obtaining Murray as his sister’s publisher. She was an unknown country girl. Why should he take her on? On the other hand he might have had great literary sense and was in the habit of reading unsolicited scripts.

Jane Austen's brother, Henry.

Jane herself was very business like with John Murray. She wrote to him on Monday 11th December 1815 from Hans Place, Henry’s house in London:

Dear Sir,

Dear Sir,

As I find that Emma is advertised for publication as early as Saturday next, I think it best to lose no time in settling all that remains to be settled on the subject, & adopt this method of doing so, as involving the smallest tax on your time.

In the first place, I beg you to understand that I leave the terms on which the Trade should be supplied with the work, entirely to your judgement entreating you to be guided in every such arrangement by your own experience of what is most likely to clear off the Edition rapidly, I shall be satisfied with whatever you feel to be the best.-“

She appears to be quite the pragmatist. It is significant to note that Murray would publish four of her six completed novels: Emma and Mansfield Park while she was alive, and Persuasion and Northanger Abbey after her death.

In the nineteenth century, the John Murray firm began publishing a series of travel books called the Murray Handbooks, which were authored by many of the great explorers of the time. The men included Sir John Franklin, who, in 1847, died exploring the North West Passage. He had also spent many years mapping the coast line of Canada. Murray also published David Livingstone, the explorer of the heart of Africa; Sir John Barrow, who wrote about South Africa; Heinrich Schlieman, the excavator and discoverer of Troy; and Isabella Bird, who visited north America and the pacific Islands. Her trips were financed by her father to help her counteract depression and backache. Both symptoms were cured in her travels: John Murray published “The Englishwoman in America,” and “Six Months in The Sandwich Islands,” both written by her about her travels.

In the nineteenth century, the John Murray firm began publishing a series of travel books called the Murray Handbooks, which were authored by many of the great explorers of the time. The men included Sir John Franklin, who, in 1847, died exploring the North West Passage. He had also spent many years mapping the coast line of Canada. Murray also published David Livingstone, the explorer of the heart of Africa; Sir John Barrow, who wrote about South Africa; Heinrich Schlieman, the excavator and discoverer of Troy; and Isabella Bird, who visited north America and the pacific Islands. Her trips were financed by her father to help her counteract depression and backache. Both symptoms were cured in her travels: John Murray published “The Englishwoman in America,” and “Six Months in The Sandwich Islands,” both written by her about her travels.

Scientists and inventors chose to be published through John Murray. They included Charles Babbage, Malthus and Lyell who wrote in 1830 “Principles of Geology,” which later inspired Charles Darwin. In 1859, the firm published Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species, and Samuel Smiles’ Self Help.

John Murray III was one of the official publishers of the Great Exhibition held in Hyde park in 1851. This exhibition promoted the industrial, economic, and military might of the Empire, although all nations were invited to contribute exhibits.

Great Exhibition

The proceeds form the exhibition were later used to create, The Albert Hall, The Science Museum, The Natural History Museum, and The Victoria and Albert museum. This area of London today is still called “Albertropolis,” because Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s husband, sponsored The Great Exhibition and the forming of the Kensington Museums. John Murray faced some opposition from some quarters when he published Queen Victoria’s letters after she died.

Prince Albert and Queen Victoria announce the opening of the Great Exhibition. Image @Getty Images.

In 1917 John Murray bought the rival publisher Smith Elder, and so added Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to their list.

In the 1930’s John Murray IV entered the firm and built up an impressive list of twentieth century writers including John Betjamin, Osbert Lancaster and Freya Stark amongst others.

In 2002 John Murray was sold to Hodder Headline, which in turn became part of Hachette UK. The company continues to publish and prosper continuing with new ideas and new authors in all fields.

As a footnote, if there is anybody reading this thinking that they would like to be published by John Murray they have a note on their website:

Submissions

Owing to the amount of time devoted to assessing solicited or commissioned work John Murray is no longer able to accept any unsolicited manuscripts or synopses, or to enter into any correspondence about them. The best way to go about getting published is to find a literary agent, who can give you advice about your work and who will know the best publishers for the kind of book you are writing.

You can find a list of literary agents in the Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook, published by A&C Black, or in The Writer’s Handbook or From Pitch to Publication by Carole Blake, both published by Pan.

Read Full Post »