“We are to have a tiny party here tonight; I hate tiny parties–they force one into constant exertion.” — Jane Austen to Cassandra, May 21, 1801, while visiting her Aunt Jane and Uncle James Leigh-Perrot in Bath

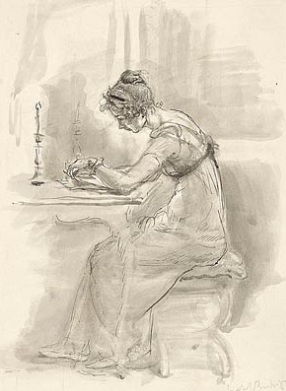

Image by Isabelle Bishop, from the Morgan Library Exhibit of Life, Work, and Legacy of Jane Austen.

Inquiring readers,

Tomorrow it will be December, a time for parties, celebrations, family gatherings, and Christmas activities, mostly in Christian regions. During Austen’s time, people associated this period with the religious calendar, as well as with pagan traditions observed since ancient times. Celebrations during Austen’s life began on Dec 6th, St. Nicholas Day, and lasted until January 6th, or 12th night — the Feast of the Epiphany.

Since 2009, this blog has posted many articles about British Christmas and New Year’s traditions, with food, dress, and customs during the Regency era and before. Austen described holiday festivities in her novels, and balls, such as the one at Netherfield Park, but none of her personal descriptions are as detailed as those mentioned in this letter to Cassandra, which tells of a large musical party that her brother Henry and sister-in-law, Eliza, held in their house in London ( 64 Sloane Street) on 25th April, 1811.

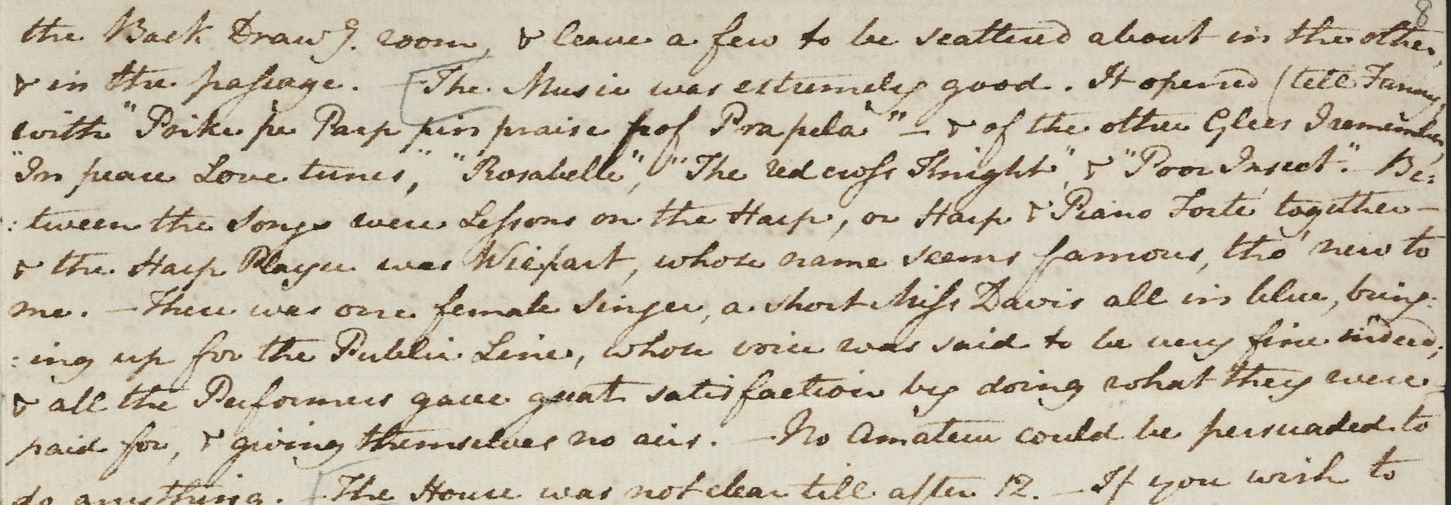

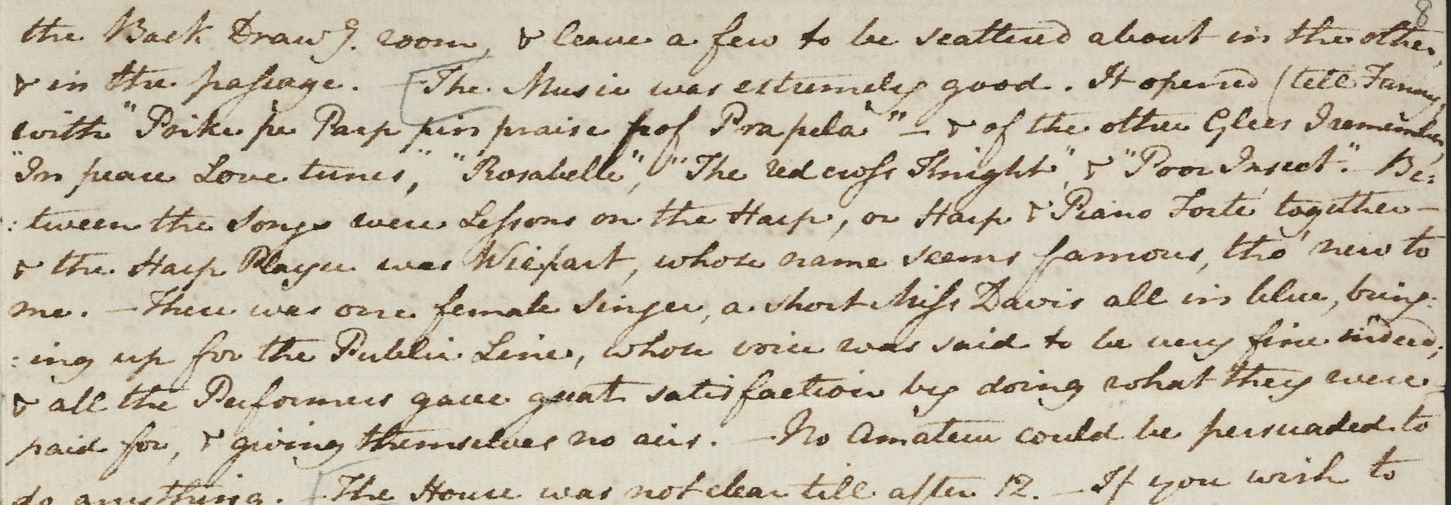

Detail of Austen’s letter to Cassandra. Image: British Library Online.

The reason for Austen’s visit was to work on proofs for Sense and Sensibility, her first published novel. I chose this letter because musical parties and get-togethers were given frequently, regardless of the time of year. The songs, decorations, and fashions might have changed with the seasons, but Austen’s description of this large party, the musicians, and the guests must have seemed quite familiar to her contemporaries, despite her spare details.

NOTE: I’ve related only the details of the party in the letter. Read the full transcript at this link to The British Library.

The Letter

- To Cassandra Austen (# From Deirdre Le Faye’s Fourth Edition of Jane Austen’s Letters)

Thursday, 25, April 1811

Sloane St Thursday April 25

Before the party:

My dearest Cassandra

… Our party went off extremely well. There were many solicitudes, alarms, and vexations, beforehand, of course, but at last everything was quite right. The rooms were dressed up with flowers, &c., and looked very pretty. A glass for the mantlepiece was lent by the man who is making their own. Mr. Egerton and Mr. Walter came at half-past five, and the festivities began with a pair of very fine soals.

(Soals is an obsolete spelling for sole, a flat fish. Hannah Glasse described a recipe for Fricasee of Soles made with lemon soles or a larger, thicker plaice fish, which fed more people.)

In this passage, Jane described the usual hustle and bustle before a grand party that we all have felt in our own lives. In this letter, she provided more details for her sister than in her novels for her readers.)

Mr Egerton is the publisher who brought out Jane’s first novel, “Sense and Sensibility”.)

Events leading up to the party:

Yes, Mr. Walter — for he postponed his leaving London on purpose — which did not give much pleasure at the time, any more than the circumstance from which it rose — his calling on Sunday and being asked by Henry to take the family dinner on that day, which he did; but it is all smoothed over now, and she likes him very well.”

(This sentence is somewhat enigmatic. Why would his postponement not give him much pleasure? How was the situation smoothed over? Mollands.net says this about Mr. Walter: [He] must have been related to Jane through her grandmother (Rebecca Hampson), who married first, Dr. Walter; secondly, William Austen. Mr. Ronald Dunning wrote a post about Rebecca Hampson for this blog just a week ago.

As the festivities began:

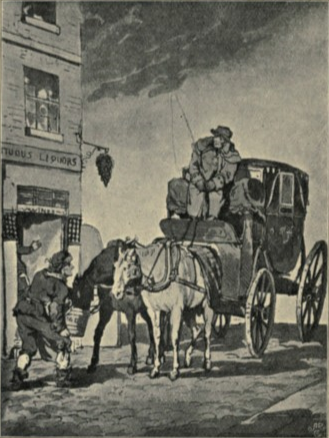

At half-past seven arrived the musicians in two hackney coaches, and by eight the lordly company began to appear. Among the earliest were George and Mary Cooke*, and I spent the greater part of the evening very pleasantly with them. The drawing-room being soon hotter than we liked, we placed ourselves in the connecting passage, which was comparatively cool, and gave us all the advantage of the music at a pleasant distance, as well as that of the first view of every new comer.”

Hackney Coach, ca 1800

(Two hackney coaches carried 6 people per coach, so we may surmise that at least 12 musicians arrived with their instruments.

Houses in town were listed as 1st, 2nd, 3rd & 4th rate, fourth being the largest and first being the smallest. Henry’s house, located on 64 Sloane Street, is today unrecognizable from its Georgian size and façade. At the time he and Eliza rented the house, it was a 3rd rate house (3 windows wide), worth between £ 350 and £ 850 with from 500 – 900 square feet of floor space.) Because Henry was a successful banker during this time and Eliza had considerable means of her own, we can surmise that the house they rented was most likely on the larger side of 500 – 900 square feet of floor space.

-

-

These facades of second rate houses on Hans Place most likely resemble 64 Sloane Street’s facade during the party, especially the unpainted brick of the house on the left.

-

-

64 Sloane Street today, with an additional story on top, and new Edwardian facade covering the Georgian era brick.

-

-

London Plane Tree, 200 years old, probably planted when Henry Austen and his wife Eliza lived in Hans Place. The London planetree is a hybrid resulting from a cross between the native sycamore and the non-native Asian planetree

Austen comments on a few acquaintances:

I was quite surrounded by acquaintances, especially gentlemen; and what with Mr. Hampson, Mr.Seymour, Mr. W. Knatchbull, Mr. Guillemarde, Mr. Cure, a Captain Simpson, brother to the Captain Simpson, besides Mr. Walter and Mr. Egerton, in addition to the Cookes, and Miss Beckford, and Miss Middleton, I had quite as much upon my hands as I could do. Poor Miss B. has been suffering again from her old complaint, and looks thinner than ever. She certainly goes to Cheltenham the beginning of June. We were all delight and cordiality of course. Miss M. seems very happy, but has not beauty enough to figure in London.”

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

(Fashion: While Austen did not describe the clothes worn by guests, Cassandra would have easily envisioned what people wore. Jane had a limited yearly budget for personal items. At a party held on Christmas, 1811, she would have refurbished a previously worn evening gown, from 1810 or before. The 1811 evening dresses had narrower skirts, mostly without trains, and hems cut at or above ankle length. Eliza de Fuillide, a woman of rank and fortune, would have worn the latest fashion. Henry Austen was quite prosperous when he rented the house at 64 Sloane Street and therefore was able to spare no expense in hosting this party.

Although Jane hated tiny parties because they required constant exertion, this musical party seemed to require as much of her attention as the former. Her wit was on full display in this letter. Miss M., sadly, has not sufficient funds nor the looks to attract a possible husband, unlike Jane Bennet in “Pride and Prejudice” or Cassandra Austen, as described by Lucy Worsley in “Jane Austen at Home.”

Many of the people mentioned by Jane are identified by Deidre Le Faye. Find their descriptions at the end of this article.**

Cheltenham, whose famous mineral waters were founded in 1716, was prominent during the Georgian era. (Christy Somers noted a short article by Carolyn S. Greet, in Jane Austen Reports for 2003, “Jane and Cassandra in Cheltenham. Diana Birchall wrote:

“In the spring of 1816 Jane and Cassandra paid a visit to Cheltenham, primarily for the sake of Jane’s health. Other members of the family had previously visited the little town, including James and his wife Mary, as Jane had mentioned in a letter of 1813. Cheltenham was then in its fashionable heyday, with its attractions being both therapeutic and social. It was still small and rustic compared with Bath, and all the buildings were still grouped along the single mile-long High Street. It was not lit with gas until 1818, and had a single set of Assembly Rooms, theatre, libraries, shops, and lodging houses. There is a description of the saline wells, which people drank from in the morning, for a laxative effect.- Reveries Under the sign of Austen”

Numbers Attending the Party:

Including everybody we were sixty-six — which was considerably more than Eliza had expected, and quite enough to fill the back drawing-room and leave a few to be scattered about in the other and in the passage.”

Jane had mentioned standing in the connecting passage, which was cooler than the two drawing rooms. The image below might be a facsimile of Henry’s and Eliza’s first floor, which typically consisted of two rooms for entertaining guests. One was larger than the other. A passageway connected the stairs to the two rooms.

The first floor:

“It was held on the first floor in the octagonal rear salon and the front drawing room. Jane told Cassandra that she spent most of the time talking to friends in ‘…the connecting Passage, which was comparatively cool, & gave us all the advantage of the Music at a pleasant distance, as well as that of the first view of every new comer.’ There were glee singers, a harpist and floral decorations” – Walking Jane Austen’s London. Louise Allen, Bloomsbury Publishing, 10 Jul 2013 .

-

-

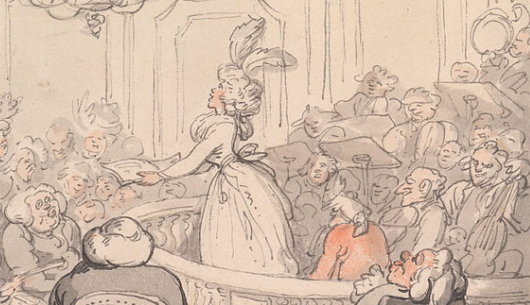

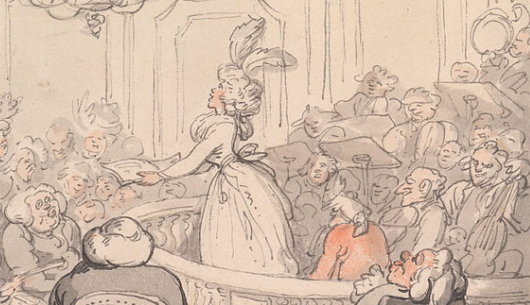

The Company at Play, detail, The Comforts of Bath, Thomas Rowlandson, 1798.

-

-

Inconveniences of a Crowded Drawing Room, George Cruikshank, 1818. Wikimedia Commons image.

-

-

An Evening Party, George Cruikshank 1826 , MET Museum image

None of the above images showed fashions even close to those worn in 1811. Formal menswear had not changed much, however, and the illustrations do give us an idea of how these parties were held.

Sixty-six people in a Regency London townhouse would have presented quite a squeeze. Even on a cold day in December, the rooms, with candles burning in chandeliers and candelabras, and heat rising from the kitchen in the basement, would have already been hot. In April, when this letter was written, the heat would have been substantial. The large group of guests would have intensified the heat even more. We do not know if the 66 guests included the musicians and singer. As Cruikshank’s images showed, card tables were set up, a common practice that Jane does not mention. One wonders if they were set up on the ground floor, near the dining room, and the floor just above the kitchen. This level would also have been easier for older people to reach. One can only conjecture about these arrangements.

Deirdre Le Faye mentions Winnifred Watson’s description of the interior of 64 Sloane Street, but the few remaining copies of her small out of print booklet, “Jane Austen in London,” are above my budget (one was listed at over $260) and so I could not read it. London townhouses built after the great London fire followed strict guidelines in both design and materials. Henry and Eliza at this juncture in their lives could probably afford a 3rd rate house with a larger square footage of floor space, perhaps even 900 sq. feet.

Using Jane’s description, and Deirdre Le Faye’s mention of this house, I found this image and quickly drew the other one very badly.

Image of a 3rd rate townhouse, 3 windows wide, 5 stories.

First floor of a 3rd rate house with 630 – 650 sq ft of floor space. Third rate houses had from 500 to 900 sq ft. of floor space.

The Music:

The music was extremely good. It opened (tell Fanny) with “Poike de Parp pirs praise pof Prapela”; and of the other glees I remember, “In peace love tunes,” “Rosabelle,” “The Red Cross Knight,” and “Poor Insect.” Between the songs were lessons on the harp, or harp and pianoforte together; and the harp-player was Wiepart, whose name seems famous, though new to me. There was one female singer, a short Miss Davis, all in blue, bringing up for the public line, whose voice was said to be very fine indeed; and all the performers gave great satisfaction by doing what they were paid for, and giving themselves no airs. No amateur could be persuaded to do anything. “

This image of Regency guests listening to musicians sits on the Alamy website. Since I have not purchased it, please click on the link to view it: https://www.alamy.com/thomas-rowlandson-a-little-evening-music-georgian-cartoon-of-a-fashionable-image9616736.html

(Interestingly, the phrase “Poike de Parp pirs praise pof Prapela” was a special language that Jane used with her niece Fanny by placing a ‘p’ in front of every word. The only one I could decipher was Harp for Parp. https://bit.ly/3o8Nb97, Jane Austen, Her Contemporaries and Herself: An Essay in Criticism, By Walter Herries Pollock, 1899, Google Books.

Mollands.net adds: Jane and her niece Fanny seem to have invented a language of their own–the chief point of which was to use a ‘p’ wherever possible. Thus the piece of music alluded to was ‘Strike the harp in praise of Bragela.’)

Miss Davis was a professional singer in London. Jane mentions that no amateur stepped up to play after listening to these fine players and singer.

About musicians during this time:

“Amateur orchestras in city taverns or in gentlemen’s clubs competed with the professional concerts that began to sprout up in public places. (- The Rage for Music, Simon McVeigh) Local musicians would be hired for assembly balls in small towns. Musicians with a more professional background would be enlisted to play at more stylish events, like the Netherfield Ball. The lady asked to lead a set would choose the music and the steps, and relay her request to the Master of Ceremonies. “ https://janeaustensworld.com/2010/07/12/jane-austen-and-music/

Cities like London or Bath provided steady incomes for musicians. In order to make ends meet, those living in rural areas traveled from town to town to the different public assemblies or parties.

Glees

Glees were quite popular at this time. Jane mentioned glee songs in Mansfield Park. “Fanny Price was the only one of Austen’s heroines who never receives any musical training at all.” Fanny was unsuccessful in enticing Edmund to go outside to look at the stars. As soon as he hears singing, he says to her, “We will stay till this is finished, Fanny.” She was mortified.

Austen also mentioned glees in this letter to Cassandra, which during her time were songs for men’s voices in three or more parts, usually unaccompanied, popular especially c. 1750–1830. These songs, by the way, were nothing like the productions created for the TV series, Glee, which ran from 2009-2015. I found one glee recording on YouTube: Reginald Spofforth- 18th Century Glee Club: L’ape E La Serpe, from Vanguard Classics.

In Peace Love Tunes the Shepherds Reed, the glee was meant for three voices, with words supplied by Walter Scott. Instrumentals were accompaniments for Piano Forte & Harp, or two performers on one Piano Forte. This glee was written by J. Atwood

This Rosabella score by John Wall Calcotte (1766-1821) in this link is for a cappella (originally). Piano accompaniment was added later by William Horsley. The lyrics were by Walter Scott.

The Red Cross Knight was written by Callcott, 1797. Also written by Callcott is the Poor Insect, a refrain from “The May Fly.”

Detail: The Concert, The Comforts of Bath, Thomas Rowlandson, 1798. Wikimedia Commons

At Party’s End:

The house was not clear till after twelve.”

This party lasted a little over four hours. London had street lights that guided guests back to their lodgings and houses. In country houses, parties, which were scheduled under the light of the full moon, often lasted until the wee early hours. After a party at a country house, Jane would often spend the night as a guest at a friend’s house, at times with her dear friend Martha Lloyd if she could manage it.

The following day:

Her party is mentioned in this morning’s paper.”

“…in the Morning Post of 25 April, which must have been very gratifying, even if the newspaper spelled her name wrong: ‘Mrs H Austin had a musical party at her house in Sloane-street.” – http://what-when-how.com/Tutorial/topic-673689/London-A-Tour-Guide-for-Modern-Traveller-10.html “Travel Reference In-Depth Information, Walk 1: Sloane Street to Kensington, A Tour Guide for the Modern Traveler.”

The guests:

* Cooke family of Great Bookham. Rev. George Cooke and his unmarried sister Mary. Their father, Rev. Samuel Cooke was Jane’s godfather.

**

- Mr. George Hampson was a baronet who chose not to use his title. He is one of Jane’s cousins through her relationship to her grandmother, Rebecca Hampson, whose second husband was William Austen.

- Mr. William Seymour, Henry Austen’s friend and a lawyer, who, it was speculated, might have considered proposing to Jane, but he didn’t.

- M. Wyndham Knatchbull, merchant in London, or Reverend Doctor Wyndham Knatchbull, the eldest son of Sir Edward Knatchbull, 8th Baronet.

- Mr. Guillemarde is probably John Lewis Guillemarde, who lived in London

- Mr. Capel Cure, who lived in London. His father, George, had first married Elizabeth Hampson, daughter of Sir George Hampson, but she died childless. Capel is the son of George Cure’s second wife.

- Captain John Simpson, brother of Captain Robert Simpson.

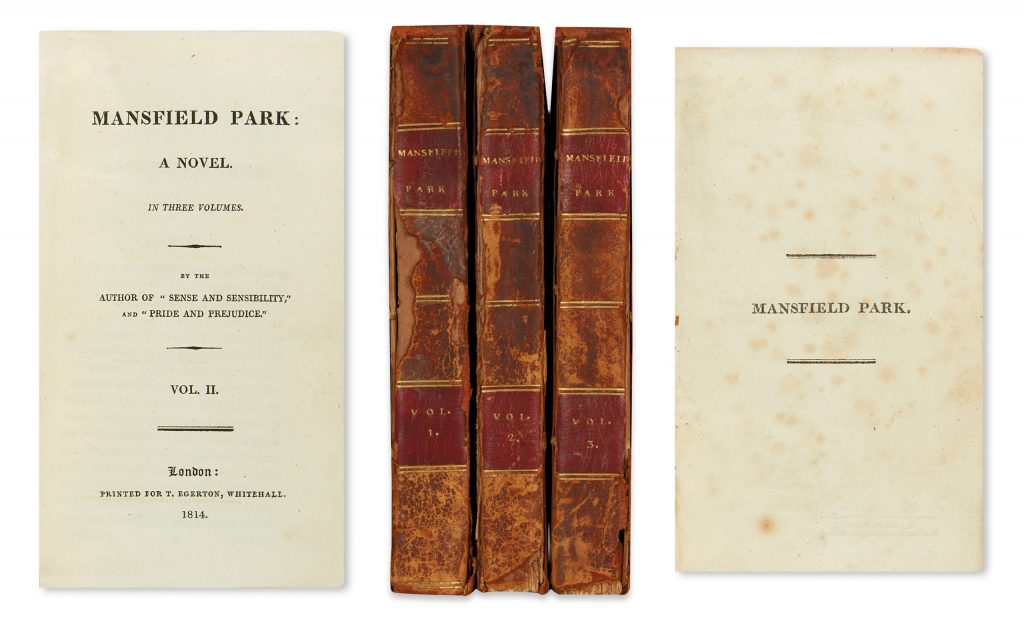

- Mr. Thomas Egerton, Austen’s first publisher. He brought out S&S, P&P, and the first edition of Mansfield Park. His presence at the party, and Jane’s purpose for visiting Henry and Eliza to complete work on Sense & Sensibility connects his attendance at the party in a marvelous way.

- Miss Maria Beckford, unmarried, lived with the Middleton family as hostess for her brother-in-law, John Middleton. When in London for the season Miss Beckford lived at 17 Welbeck Street. (Le Faye, p 495)

- Miss Middleford. No explanation by Ms. Le Faye.)

Additional sources:

Characteristics of the Georgian Townhouse , June 3, 2009 , Jane Austen’s World, Vic

Jane Austen’s Letters, 4th Edition, Deirdre Le Faye, 2011, Oxford University Press.

Jane Austen’s visit to Sloane Street , Kleurijk Jane Austen, 9-2014

Jane Austen, Her Contemporaries and Herself: Walter Herries Pollock · 1899 – Explanation of “Poike de Parp pirs praise pof Prapela”

Georgian Terrace Houses, April 27, 2021, Random Bits of Fascination.com, Georgian Townhomes

Thank you, Tony Grant, for contributing the 3 current photographs of Hans Place (2) and of 64 Sloane Street (1).

Read Full Post »