A Book Review by Brenda S. Cox

“Marianne’s ‘excess of sensibility’ almost destroys her reputation, her health and her happiness, wihle Elinor’s more guarded behaviour is rewarded. But that is fiction; what of real life?”—Prologue to Jane and Dorothy, by Marian Veevers

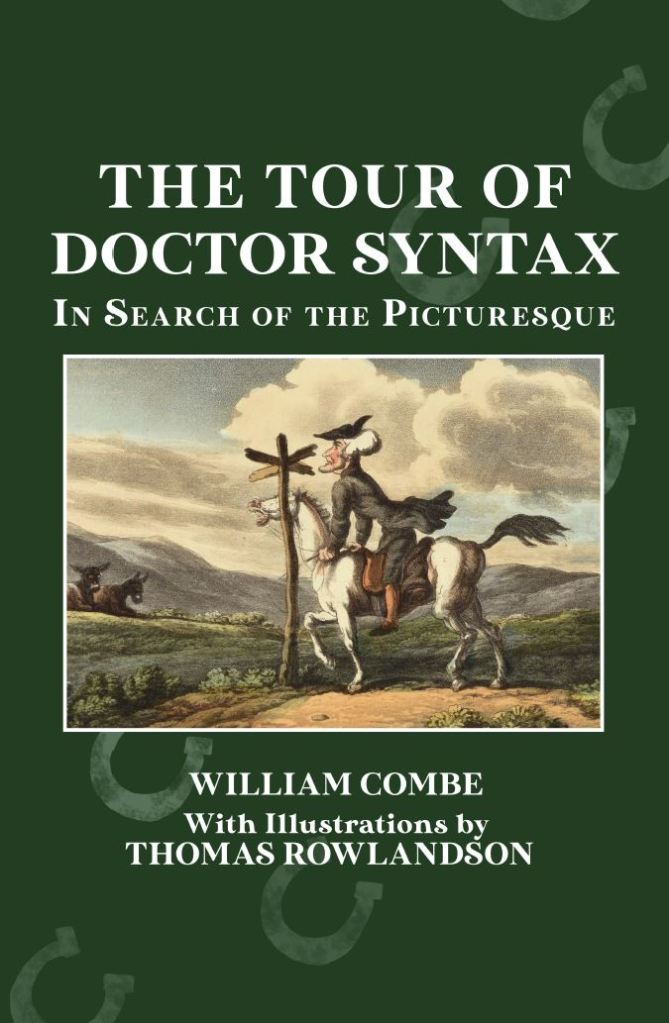

Jane and Dorothy: A True Tale of Sense and Sensibility, The Lives of Jane Austen and Dorothy Wordsworth, by Marian Veevers. The lovely cover attracted my attention as I perused a library book table focused on Jane Austen.

I had read a review of this book some time ago and suggested it to a literary friend, who said there was no connection between Jane Austen and Dorothy Wordsworth, sister of poet William Wordsworth. But I decided to check out the book and find out how the author connects them. I’m glad I did, as it was a fascinating read.

Jane Austen and Dorothy Wordsworth

Jane and Dorothy follows the lives of two women, living at approximately the same time, who never met. Parallel, never intersecting, similar in some ways and contrasting in others. Connections with Austen’s novels are intertwined in their stories. Jane (1775-1817) is compared to Elinor Dashwood, with strong feelings controlled by reason and religion. Dorothy (1771-1855) is more like Marianne, focusing on her emotions. In one teenage letter to a friend who was sympathizing with her misery, Dorothy wrote, “You cannot think how I like the idea of being called poor Dorothy . . . I could cry whenever I think of it.”

Both were writers. Jane Austen, of course, had four novels published during her lifetime, two more shortly after her death, and her Juvenilia and letters published years later.

Dorothy Wordsworth wrote journals, mostly about her ramblings in nature with her brother, who became a famous poet of Romanticism. William Wordsworth used his sister’s journals as inspiration and a source of details for his poetry. His discussions and experiences with her also inspired him. A few of Dorothy’s own poems were published during her lifetime, but her journals and her travel narrative of a trip to Scotland were only published after her death.

Both Jane and Dorothy were dependent on their brothers later in their lives. Austen and her mother and sister were financially supported by her brothers after her father’s death, and her brother Edward provided Chawton Cottage where she wrote and rewrote her novels.

Dorothy lost her parents early in life and lived with various relatives as a poor relation, similar to Austen’s Fanny Price, until she threw in her lot with her brother William. Dorothy loved William passionately. (The author discusses rumors of sexual involvement and concludes that the rumors were false.) Dorothy devoted the rest of her life to her brother and, eventually, to his wife and children. Their financial situation was much harder than the Austens’, but they survived.

It was interesting to see the similar social and financial restrictions that society placed on both Jane and Dorothy, particularly as unmarried women, and to see how Jane’s life might have played out differently in other circumstances.

C.E. Brock, public domain.

Austen and Drama

Having read so much about Jane Austen, I wasn’t expecting new insights into her life from this book. However, I found several. I’ll give just one example, from pages 47-50 of Jane and Dorothy.

Veevers discusses Austen’s attitude toward amateur home theatricals in Mansfield Park. Many have commented on the fact that Austen’s family performed such plays when she was growing up, and that she couldn’t really have thought they were wrong. Perhaps it was just the specific circumstances at Mansfield Park that made it wrong, or her attitude had changed due to the growing Evangelical disapproval of drama, or she was attributing disapproval to Fanny and Edmund.

However, Veevers speculates that, first, Jane may not have participated herself in those plays when she was growing up. She says the only evidence we have for that is Jane’s cousin, Phylly Walters, who wrote that “all the young folks” were participating in a performance in 1787—that is rather vague. Or Jane may have participated without enjoying it.

While Austen’s family approved of amateur theatricals, we don’t have to assume that she herself agreed. Instead, those experiences of plays in the Steventon barn may have shown Jane “the dark underbelly” of such practices. Veevers says any “modern-day member of an amateur dramatics company” would recognize these issues. She continues,

“Jane Austen gives an unflinching insider’s view of everything that is worst about amateur acting, from the concealed, but overwhelming self-interest of Julia and Maria Bertram who each hope to have the best part in the play ‘pressed on her by the rest,’ to the self-indulgent over-rehearsal of favourite scenes by some actors, and the insidious, self-gratifying criticisms of others’ performances—‘Mr Yates was in general thought to rant dreadfully . . . Mr Yates was disappointed in Henry Crawford . . .’” etc., etc. “There can be no doubt that this detailed understanding . . . came from real observation. It would seem that brother James’s annual productions in the Steventon barn were riven by jealousy, bad-feeling and unkindness.”—Jane and Dorothy, p. 49

Veevers goes on to speculate that Jane’s opinions may have been influenced by her dear friend Anne Lefroy. Mrs. Lefroy was a clergyman’s wife who apparently disapproved of amateur theatricals, politely declining to participate when a friend invited her. (Also, I would add, it appears those Steventon theatricals were an opportunity for flirtation between Jane’s still-married cousin Eliza and two of her brothers, so perhaps Henry Crawford and Maria Bertram’s fictitious flirtation also had a basis in past experience.)

I don’t think I personally agree with the idea that Austen disapproved of such theatricals, though. Austen certainly enjoyed the professional theatre, “good hardened real acting,” as Edmund Bertram called it, distinguishing that from amateur performances. Austen did, though, write several short, comic plays as a teenager, which may have been acted by her family. On a visit to Godmersham, she and Cassandra acted—most likely by reading aloud— a couple of plays with their nieces and nephews. (The Spoilt Child and Innocence Rewarded, according to Fanny Knight’s diary). Of course, that would have been on a much more limited scale than the play at Mansfield Park, with presumably less objectionable plays.

Whether Austen objected to amateur dramatics in general is questionable, but certainly she had seen enough to very realistically show the pitfalls of such productions in Mansfield Park. So I appreciated this insight from Jane and Dorothy.

H.M. Brock, public domain.

Spinsterhood

The book extensively explores attitudes toward “old maids” in Austen’s society. It’s easy to forget that Austen herself probably experienced prejudices against unmarried women. She certainly sometimes felt herself a poor relation at her wealthy brother’s Godmersham estate. She often lacked autonomy: her living situations and travels were dictated by her parents or brothers. Perhaps those feelings helped her create Fanny Price, dependent and marginalized.

Jane and Dorothy points out many illuminating parallels between Sense and Sensibility and Mansfield Park. Fanny is much like Marianne, with strong feelings. However Austen, when she was a more mature writer, made Fanny spiritually stronger, more nuanced, and with greater depth.

C.E. Brock, public domain.

End of Life

Dorothy lived much longer than Jane. Sadly, though, Dorothy’s last twenty years were spent with “her mind completely broken.” She had given her life to taking care of her family; that same family gave her loving care for those long years. It’s been speculated that she may have had some kind of dementia, or possibly severe depression. (She suffered, in fact, similarly to William Cowper in his final years. Cowper’s poetry, by the way, impacted both women.)

Of course we all wish that Jane had lived longer and written more. However, thinking of the many ways a spinster (like Miss Bates, for example, or Dorothy Wordsworth) might end up in Austen’s world, perhaps Jane’s earlier demise from an unknown disease was not the worst possible ending for her. The recent book and series Miss Austen also imagines long-lived Cassandra suffering late in her life.

As Veevers concludes,

“Jane and Dorothy were two unmarried, childless women who had failed to fulfil the destiny that their society prescribed for their sex. But they neither drooped nor withered as [1838 writer] Carlisle expected, nor developed the chagrin and peevishness which Dr. Gregory [1774] believed inseparable from their condition. Instead they forged their own meanings from their lives. . . . Jane and Dorothy were not simply products of their time. They made choices in their lives, and it was those choices which defined them.”

I found it fascinating to trace the choices of these two parallel lives, and the resulting joys and sorrows, during the same time in history. Well-written, easy to read, and compelling, Jane and Dorothy is worth reading for anyone who wants to get deeper into “Jane Austen’s World.”

Brenda S. Cox is the author of Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England. She also blogs at Faith, Science, Joy, and Jane Austen.