Dear readers, I have an exquisite new book to share with you today: Jane Austen’s Wardrobe by Hilary Davidson!

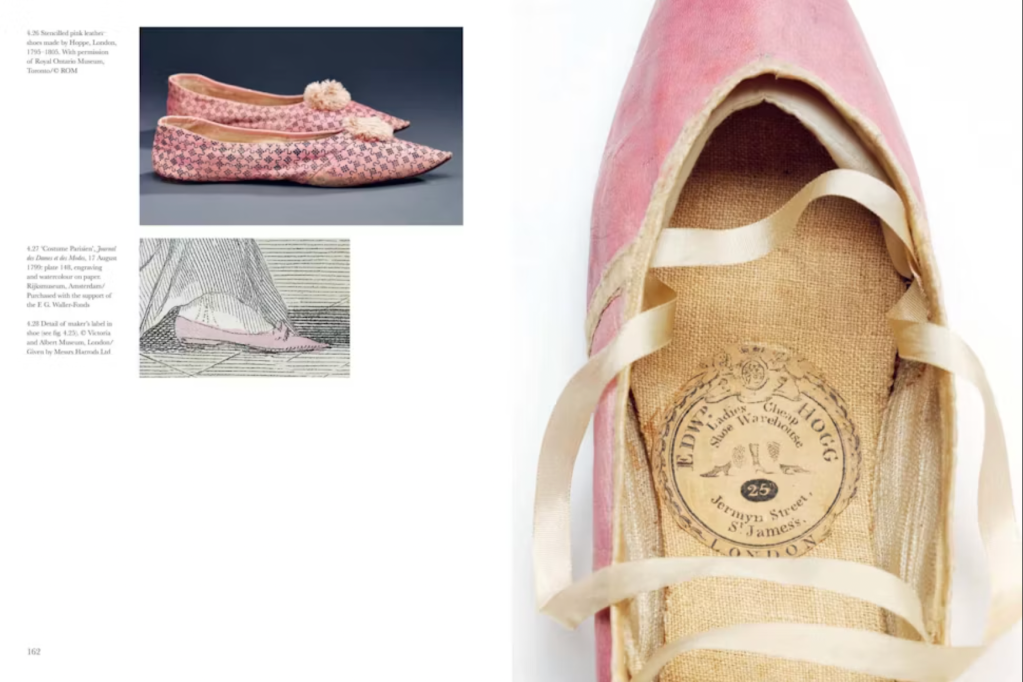

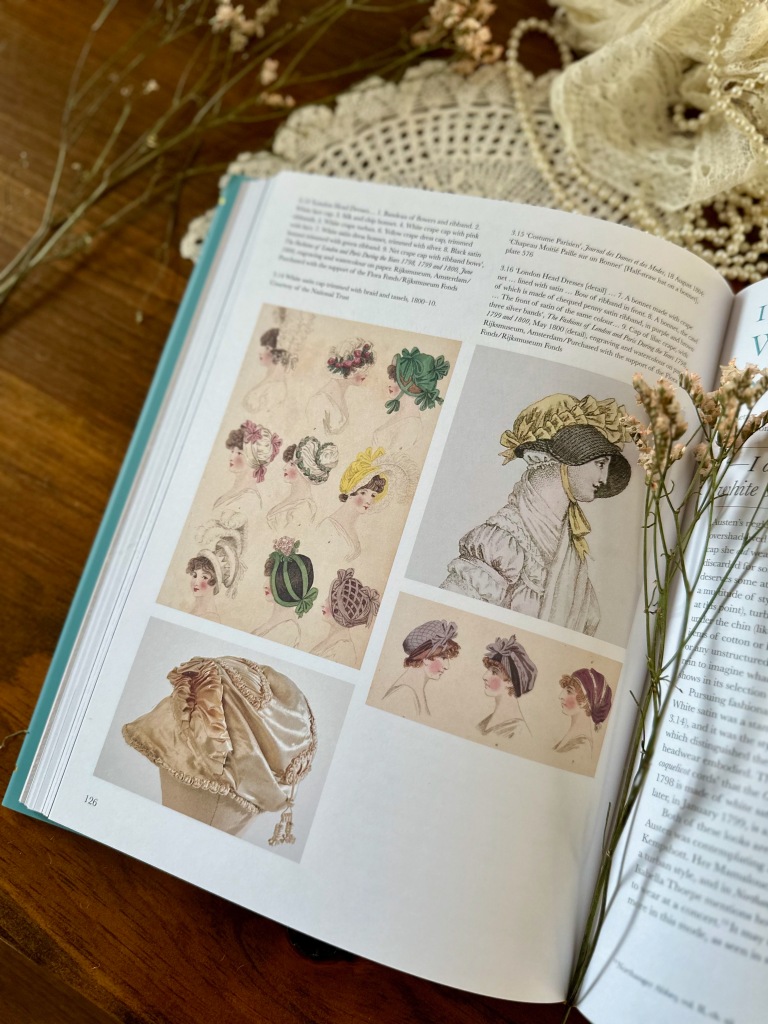

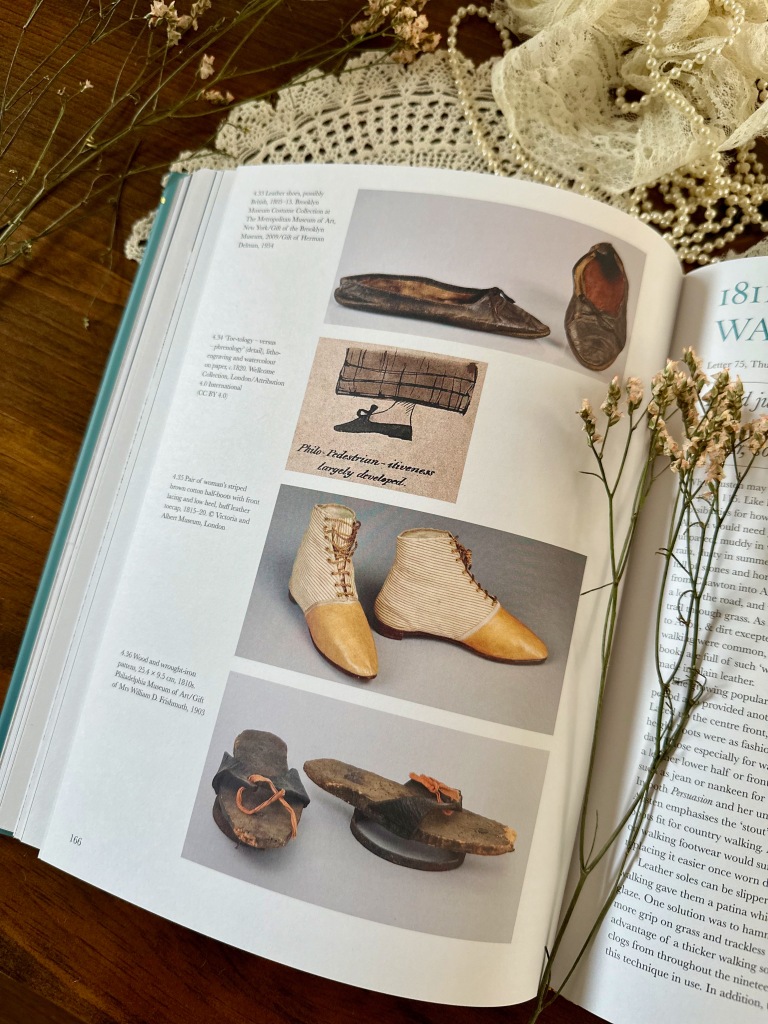

Filled with incredible photos and written information, it’s one of the most detailed books I’ve seen in a long time on this topic. Not only is it beautiful, it is filled with fascinating information on one of my most favorite topics.

This is my new favorite book on Jane Austen’s Regency Fashion. I know I’ll continue to pour over it for years to come!

Austen’s Wardrobe by Category

Within the pages of this lovely book, Davidson works her way through Austen’s personal wardrobe chronologically, from head to toe. Davidson’s system for cataloging Austen’s wardrobe is fascinating! For those of us who delight in a linear and/or chronological order to a wide and varied topic, Davidson definitely checks all the boxes.

First, she breaks all of Austen’s clothing down into the following categories:

- Clothes Press: Gowns

- Closet: Spencers, Pelisses and Outer Garments

- Band Box: Hats, Caps and Bonnets

- Shelves: Shawls, Tippets, Cloaks and Shoes

- Dressing Table: Gloves, Fans, Flowers, Trims and Handkerchiefs

- Jewelery Box: Necklaces, Rings and Bracelets

- Drawers: Undergarments and Nightwear

Davidson even includes several pages of sketches, descriptions, and explanations for Jane’s “Portrait Gown” – which I found completely engrossing.

Austen’s Letters Quoted

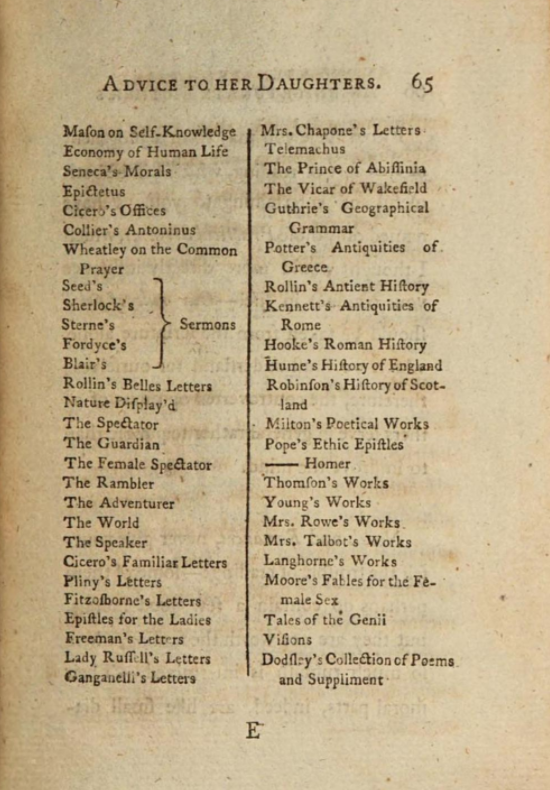

Next, Davidson utilizes Austen’s personal letters to explore every inch of Austen’s wardrobe, working her way through each category in chronological order. To do this, she shares one quote at time, citing portions of letters that mention Austen’s clothing. Then, for each article of clothing, every hat, and every piece of jewelry, she explains that quote in great detail and provides photos to aid our understanding.

For instance, Austen writes this in Letter 65:

“I can easily suppose that your six weeks here will be fully occupied, were it only in lengthening the waists of your gowns. I have pretty well arranged my spring & summer plans of that kind, & mean to wear out my spotted Muslin before I go. –You will exclaim at this–but mine has signs of feebleness, which with a little care may come to something.”

Tuesday 17 – Wednesday 18 January, 1809, Castle Square

Davidson provides photos of spotted muslin fabric swatches and a photo of a dress made of spotted muslin, dated 1805-10. Then she explains the muslin fabric, provides quotes from Austen’s novels about muslin dresses, and explains Austen’s quote. She goes over the dress styles, what was involved in “lengthening the waist” of a gown, the meaning of “worked” fabric, and the ins and outs of fragile fabrics of that time period, including how women used belts to cover holes in the fabric when a waist was lengthened.

I found this incredibly interesting because I’ve always been curious about Austen’s extensive quotes about her dresses and hats in her letters. The result is a delightful (and sometimes hilarious) tour through Jane Austen’s closet in her own words, with pictures and explanations to match!

Here are several more examples, provided by Yale University Press:

Informative and Beautiful

Like many of Austen’s heroines, this book is both intelligent and beautiful. Inside and out, this book is absolutely stunning. The photos provide a detailed look into Jane Austen’s clothing that is hard to find, especially all in one place. This book feels like a worldwide museum tour of all the most exquisite clothing artifacts from Austen’s time.

This is the perfect addition to any Jane Austen library – and it will look gorgeous on your coffee table!

Book Description

Hilary Davidson delves into the clothing of one of the world’s great authors, providing unique and intimate insight into her everyday life and material world.

Acclaimed dress historian and Austen expert Hilary Davidson reveals, for the first time, the wardrobe of one of the world’s most celebrated authors. Despite her acknowledged brilliance on the page, Jane Austen has all too often been accused of dowdiness in her appearance. Drawing on Austen’s 161 known letters, as well as her own surviving garments and accessories, this book assembles examples of the variety of clothes she would have possessed—from gowns and coats to shoes and undergarments—to tell a very different story.

The Jane Austen Hilary Davidson discovers is alert to fashion trends but thrifty and eager to reuse and repurpose clothing. Her renowned irony and wit peppers her letters, describing clothes, shopping, and taste. Jane Austen’s Wardrobe offers the rare pleasure of a glimpse inside the closet of a stylish dresser and perpetually fascinating writer.

About the Author

Hilary Davidson is a dress, textile and fashion historian and curator. Her work encompasses making and knowing, things and theory, with an extraordinary understanding of how historic clothing objects come to be and how they function in culture.

Hilary is equally skilled in analysing historical and archaeological material culture artefacts; presenting engaging, fascinating talks to diverse audiences; and producing influential academic research.

Her extensive experience includes:

- Scholarly research

- Lecturing, teaching and public talks

- Broadcasting and journalism

- Historic dressmaking

Hilary trained as a bespoke shoemaker in her native Australia before completing a Masters in the History of Textiles and Dress at Winchester School of Art (University of Southampton) in 2004. Since graduating, Hilary’s practice has concerned the relationship between theoretical and highly material approaches to dress history, especially in the early modern and medieval periods.

As a skilled and meticulous handsewer, she has created replica clothing projects for a number of museums, including a ground-breaking replication of Jane Austen’s pelisse. At the same time she lectured extensively on fashion history, theory and culture, on semiotics, and cultural mythologies, especially red shoes.

In 2007 Hilary became curator of fashion and decorative arts at the Museum of London. She contributed to the £20 million permanent gallery redevelopment opening in 2010, and curated an exhibition on pirates, while continuing to publish, teach and lecture in the UK and internationally. In collaboration with Museum of London Archaeology, Hilary began analysing archaeological textiles and continues to cross disciplines by consulting in this area in England and Australia. She also worked on the AHRC 5-star rated Early Modern Dress and Textiles Network (2007-2009) and from 2011 has appeared as an expert on a number of BBC historical television programmes, and as a frequent radio guest speaker in London and Sydney.

From 2012 Hilary worked between Sydney and London as a freelance curator, historian, broadcaster, teacher, lecturer, consultant and designer, while working on a PhD in Archaeology at La Trobe University, Melbourne. In addition to historical studies she has been a jewellery designer, graphic designer, photographer, gallerist, and worked in retail fashion and vintage clothing. In 2022 she moved to New York City to take up the role of Associate Professor and Chair of the MA Fashion and Textile Studies: History, Theory, Museum Practice at the Fashion Institute of Technology.

Hilary has taught and lectured extensively, including at the University of Southampton, Central St Martins, the University of Cambridge, the University of Glasgow, New York University London, The American University Paris, Fashion Design Studio TAFE Sydney and the National Institute of Dramatic Art (NIDA), Sydney. She speaks regularly at academic conferences and to the public. Her first monograph book was Dress in the Age of Jane Austen (2019) followed by Jane Austen’s Wardrobe in 2023. Her extensive publications can be found on Academia and ResearchGate.

To Order the Book:

You can order the book by clicking HERE

or by clicking the image below:

Recommended Book Gift

I hope you’ve enjoyed this short tour of this stunning new book by Hilary Davidson. If you’re looking for a gift for a fellow Jane Austen fan, or if your friends or family members need an idea for a gift for you this holiday season, I highly recommend this one!

RACHEL DODGE teaches college English classes, gives talks at libraries, teas, and book clubs, and writes for Jane Austen’s World blog. She is the bestselling author of The Little Women Devotional, The Anne of Green Gables Devotional and Praying with Jane: 31 Days Through the Prayers of Jane Austen. Now Available: The Secret Garden Devotional! You can visit Rachel online at www.RachelDodge.com.