It is interesting to know that the 18th Century author, Fanny Burney, introduced several new words into the English language through the literary form. Through Evelina, she is the first known person to use words which are still so commonplace now, such as a-shopping, seeing sights, break down and grumpy.

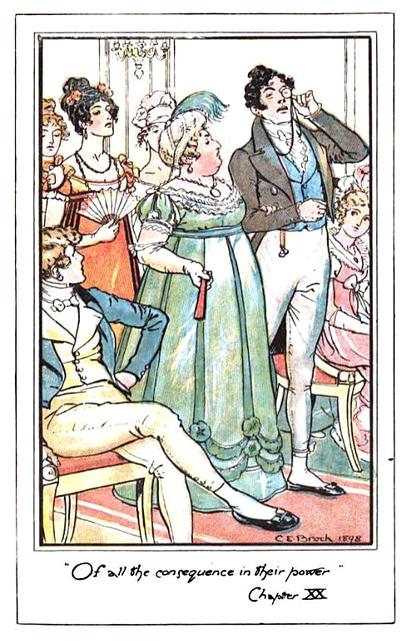

Have you ever wondered what inspired Jane Austen to use dialogue as a clever way to personify her characters? Was the romantic charlatan, Mr Willoughby, a product of Jane’s imagination or an imprint of her early reading? Read on!

In her novels and letters, Jane Austen made several references to her favourite authors, and amongst her favourites were always Frances (Fanny) Burney and Maria Edgeworth. Fanny Burney wrote Evelina in the 1770’s, when Jane Austen was still an infant, and Cecilia soon after, and Jane grew up reading these stories. As you read through her novels, it becomes evident that Jane Austen drew inspiration from them.

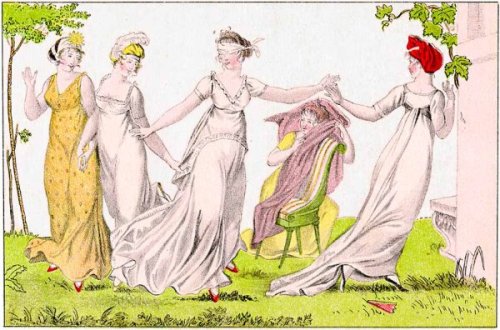

Evelina is a lengthy novel, which was originally written in 3 volumes, according to the custom of the time. Like Northanger Abbey, Evelina is a coming-of-age novel, with the apt subtitle “The History of the Young Lady’s Entrance Into the World”. The heroine is a girl of obscure birth who has been raised by her loving foster father, Mr Villars, in a comfortable home. Like Catherine, Evelina is set to ‘come out’ and enter the society to lure the attentions of eligible young men.

Evelina is chaperoned to London, where she visits the numerous theatres, operas and pleasure gardens frequented by fashionable society. As Evelina enters into society, she comes across one odious character after another and must defend her virtue against characters of low morals. Not unlike Catherine, Evelina is all innocence and youthfulness and is shocked to experience the realities of London society. She is repulsed by the lewd behaviour of men that she meets and soon wishes that she had never left Berry Hill, her home. In short, her trips are a journey from innocence to experience (to quote Blake).

Evelina is a satire of fashionable life. Like Jane Austen, Frances Burney is an excellent satirist and parodies characters through her excellent mimicry. It is in the dialogue that she really shows her ingenuity. In the preface of Evelina, Burney describes her style as follows:

To draw characters from nature, though not from life, and to mark the manners of the times, is the attempted plan…”

As a key component of her style, Burney reveals personality through her use of language. Her highest-ranking characters (e.g. Lord Orville, Lady Louisa) use extremely formal register, as opposed to the lower-ranking, more vulgar characters (e.g. Captain Mirvan, Madame Duval), who Burney mimics endlessly.

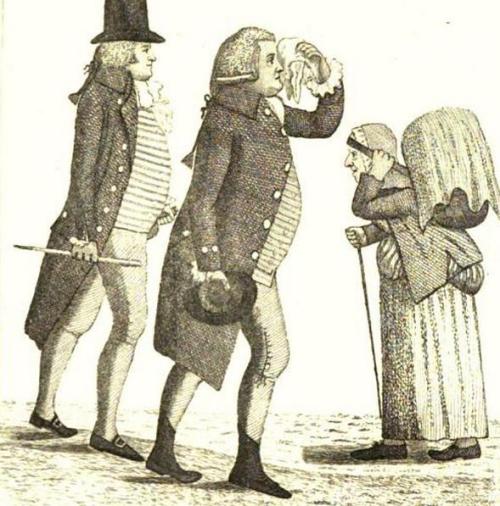

The grotesque Captain Mirvan who enjoys abusing the would-be French woman, Madame Duval, uses crass language with plenty of nautical references.

The old buck is safe – but we must sheer off directly, or we shall be all aground.”

On the other hand, Madame Duval’s bad grammar reveals her lack of breed and education.

This is prettier than all the rest! I declare, in all my travels, I never see nothing eleganter.”

As Evelina meets her ‘vulgar’ cousins in London, the scene reminds me of Mansfield Park where Fanny meets her real family in Portsmouth after several years and feels out of place, having got used to the genteel, polished manners of a country house (Burney uses the word “low-bred” to describe Evelina’s relatives).

![Evelina1_thumb[3]](https://janeaustensworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/evelina1_thumb3.jpg?w=500)

Like Austen’s novels, Evelina too is written in somewhat archaic 18th Century language with a preference for long, complex sentences – a style that Jane Austen certainly assumed. Thankfully, this Oxford edition has been carefully edited by Edward Bloom, with detailed notes on 18th Century vocabulary and manners… to read the rest of the post, click here to enter Austenised by Anna.

Thank you, Anna, for giving me permission to link to your post!

Read Full Post »

![Evelina1_thumb[3]](https://janeaustensworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/evelina1_thumb3.jpg?w=500)