It’s a truth universally acknowledged that after a bride and groom consummate the marriage the pitter patter of little feet will surely follow (and follow and follow and follow). Such was the case during Jane Austen’s day. Her mother bore eight children and luckily survived her ordeals. The wives of Jane’s brothers Edward and Frank did not, both dying in childbirth with their eleventh child. That these two women were able to survive so many pregnancies was a miracle in itself, given that the chance of a woman dying in childbirth at the time was 20%.

Queen Charlotte, King George IIIs consort, gave birth to 15 children in 21 years. The King and Queen are depicted with their 6 eldest.

Deborah Kaplan writes in Jane Austen Among Women:

“On the birth of his fourteenth child in 1817, Thomas Papillon received this advice within a letter of congratulations from his wife’s uncle, Sir Richard Hardinge: It is now recommended to you to deprive Yourself of the Power of Further Propagation. You have both done Well and Sufficiently.”

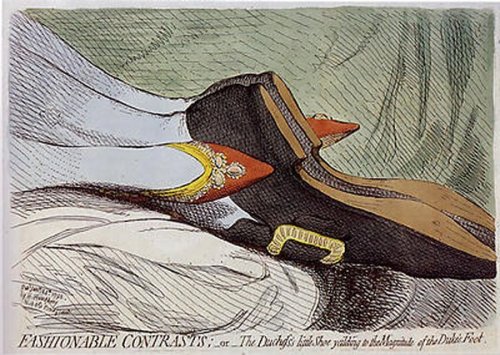

The fashionable mamma, or the convenience of modern dress, James Gillray

Abstinence was one method of birth control, as Sir Richard recommended. Breast feeding was another. If a mother breasfed her child for 3-4 years, the pregnancies would be naturally spaced inbetween periods of amenorrhea (the absence of menstruation). While breastfeeding regained some popularity during the Georgian and Regency eras, women did not feed their babies long enough to supress menstruation for very long and often handed them over to a wet nurse. Cassandra Austen farmed her children to a nurse in a nearby village after six to eight months, guaranteeing that her lactation would soon cease and that she would soon be fertile again. The common belief that having intercourse during lactation would in some way harm the mother and child did offer some added protection from pregnancy, but large families were still common.

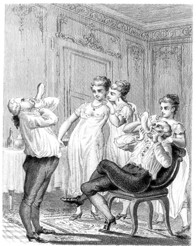

Amanda Vickery shows a bachelor cadging food from an irritated married friend. The poor young man probably lived in a modest rented room.

Social customs also served to keep pregnancies down. Amanda Vickery mentioned in At Home with the Georgians that a bachelor needed to acquire a house and reliable income before he could seriously contemplate marriage. Such acquisitions took years to amass and would hold up the young man’s inevitable role as parent. Once the young man could afford to marry, however, his long period of delayed consummation with a chaste woman ended and he would waste no time in siring a legitimate child.

A woman’s chaste reputation owed much to the urgent necessity of her not getting pregnant before marriage. Conceiving a child out of wedlock turned a woman into a pariah. In medieval times a chastity belt guaranteed that no bride would enter her marriage bed sullied. Unfortunately, these contraptions came in only one size and were therefore extremely uncomfortable for the larger sized woman.(Johannah Cornblatt, Newsweek). Update: Information about chastity belts in medieval times is being debunked these days as a myth. See links in the comment section below.

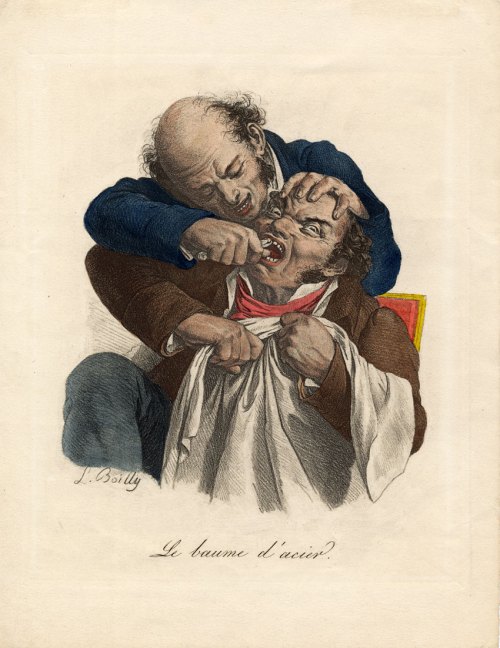

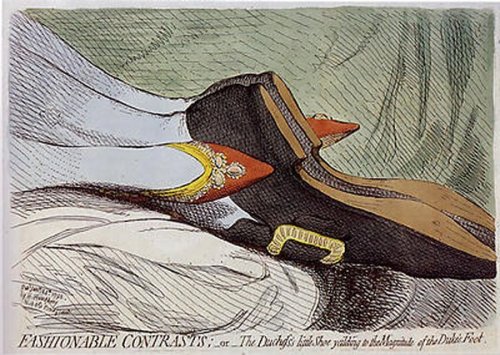

James Gillray's priceless caricature.

Married couples anxious to reduce their number of offspring (or who had reached their limit of 10, 11, or 15) tried coitus interruptus and the rhythm method. Since the female fertility cycle was not fully understood until the early twentieth century, the latter form of birth control resembled a game of Russian Roulette more than family planning. Several religious institutions, the Catholic Church in particular, frowned upon a married couple attempting any form of birth control at all, but there was evidence that birth control was effectively practiced. “Some couples managed to delay the first conception within marriage and few babies were born in the months of July and August, when the heaviest harvest labor took place.”-History of Birth Control.

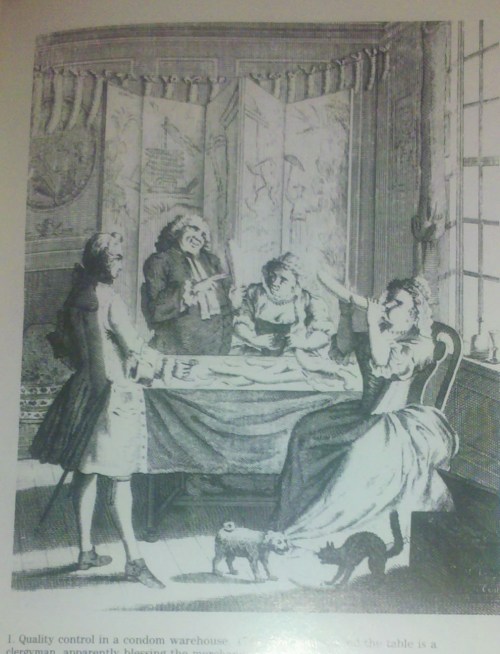

Condoms, which were made of linen soaked in a chemical solution or the lining of animal intestines, had been in use for centuries, but this method of birth control was linked to vice and was mostly practiced in houses of ill repute.

Casanova blowing up a condom with prostitutes looking on.

Giacomo Girolamo Casanova (1725-1798) was among the first to use condoms to prevent pregnancy. The famous womanizer called the condom an “English riding coat.” His memoirs also detail his attempt to use the empty rind of half a lemon as a primitive cervical cap. The engraving shows the Italian seducer blowing up a condom. The photo shows an early 19th-century contraceptive sheath made of animal gut and packaged in a paper envelope. – Newsweek

Condom made of animal gut with paper envelope. Image @Newsweek

One can imagine that such clumsy barriers to impregnation failed on too many occasions to count, although they did manage to prevent venereal disease.

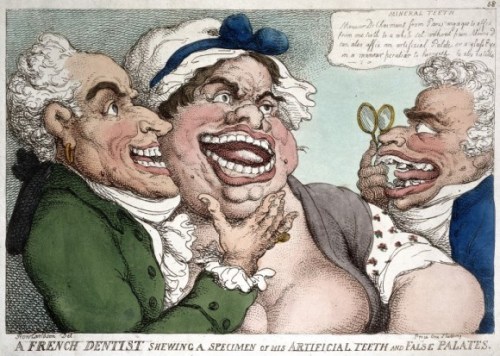

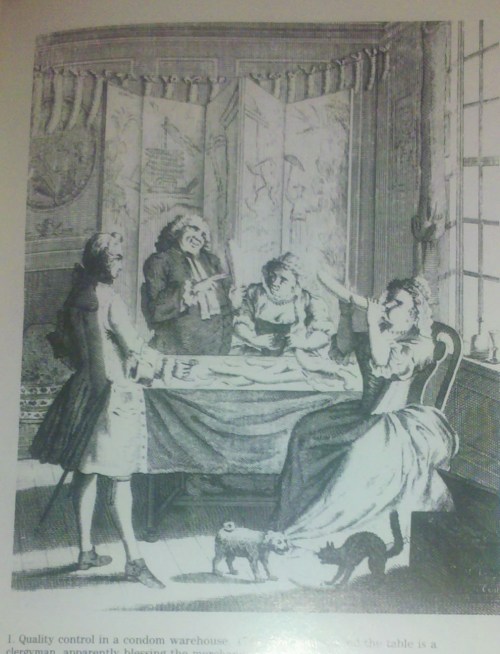

Georgian caricatures made much sport of condoms. This one is entitled: "Quality control in a condom warehouse."

There were other means of pregnancy prevention. Aristotle recommended anointing the womb with olive oil. His other spermicides included cedar oil, lead ointment, or frankincense oil.

Pessaries, 1755. Image @The Global Library of Women's Medicine

“The pessary [mechanical tool or device used to block the cervix] was the most effective contraceptive device used in ancient times and numerous recipes for pessaries from ancient times are known. Ingredients for pessaries included: a base of crocodile dung (dung was frequently a base), a mixture of honey and natural sodium carbonate forming a kind of gum. All were of a consistency which would melt at body temperature and form an impenetrable covering of the cervix. The use of oil was also suggested by Aristotle and advocated as late as 1931 by birth control advocate Marie Stopes.” – History of Birth Control

Other societies had used methods of blocking sperm including plugs of cloth or grass in Africa, balls of bamboo tissue paper in Japan, wool by Islamic and Greek women, andlinen rags by Slavic women. Ancient Jews used a sea sponge wrapped in silk and attached to a string. – History of Birth Control.

Many young girls who had been seduced, engaged in pre-marital sex, or been raped would attempt not to get pregnant by any means. The unfortunate women who did were ostracised, much like Colonel Brandon’s young charge, Liza, who had been enticed by Willoughby in Sense and Sensibility to give up her virginity. These women were frantic to end their pregnancies rather than lose their standing in society or their livelihood, for no pregnant unmarried woman could work as a maid, shopgirl, or seamstress. They would try anything to end their pregnancies, including ingesting turpentine, castor oil, tansy tea, quinine water into which a rusty nail was soaked, horseradish, ginger, epsom salts, ammonia, mustard, gin with iron filings, rosemary, lavender, and opium. Severe exercise, heavy lifting, climbing trees, jumping, and shaking were also attempted, in most instances to no avail. – History of Birth Control

Tess of the D'Urberfield and her baby, Sorrow. Thomas Hardy wrote about the consequences of seduction. (Nastassia Kinski as Tess, 1980)

Infanticide has been practiced since the dawn of time, most famously with the Greeks, who left deformed babies to die outdoors. In Regency times, desperate women would leave their babies in the streets to die. Many left their infants at workhouses, a form of infanticide as the quote below attests, and a large number, too poor to support themselves and unable to work off their debts, wiled away their time in prison.

“When the poor stayed with their children in workhouses, the outcome was little better. Between 1728 and 1757, there were 468,081 christenings and 273,930 infant deaths in those younger than the age of 2 in London workhouses. Foundling hospitals and workhouses were institutionalized infanticide machines.” – Global Library of Women’s Medicine

Women at Bridewell Prison, 1808. Rowlandson and Pugin for Ackermann's Repository of Arts

Once children were born and the family was large, it was not unusual to farm out a few children, some to work in their childhood, as Charles Dickens did, and other to live with relatives, as was the case with Fanny Price, who lived with her aunt’s family in Mansfield Park and Edward Austen Knight, who was adopted by a rich, childless couple.

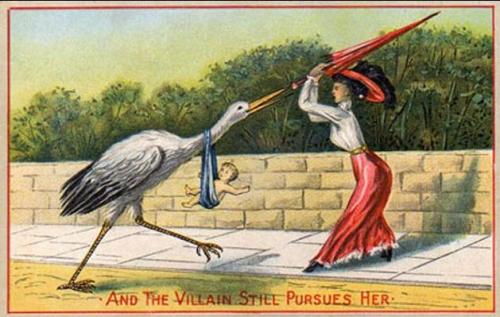

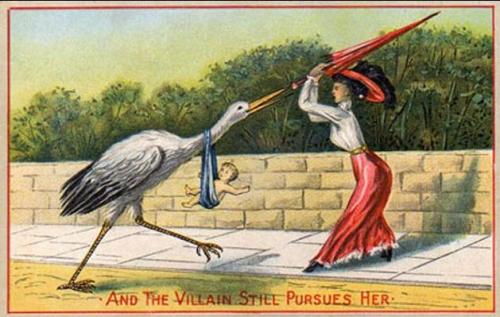

Early 20th century attitude towards an unwanted child. Image @Newsweek

It has been said that families had many children during the 18th and 19th centuries because of the high rate of infant mortality and the need for many helping hands on the farm. But as society became industrialized, large families became a hindrance. With many mouths to feed and limited resources (except in the case of the rich), it is no wonder that couples since time immemorial have searched for ways to limit the number of their offspring. Update: As Nancy Mayer rightly pointed out in her comment, most women during the Georgian and Regency eras thought it their duty to bear their husbands children and oversee the family household. The matter of family planning might well have been influenced by women of a certain class who could not allow pregnancies to interfere with the rhythm of the work cycle, single women who were desperate to seek ways to end their pregnancies before their condition became obvious, and in houses of ill repute, where condoms would offer some protection against disease. Mistresses and prostitutes would find pregnancies to be more of a hindrance than help in their work. I have often wondered, for example, how Emma Hamilton managed to have so few children and yet enjoy the charms of so many men.

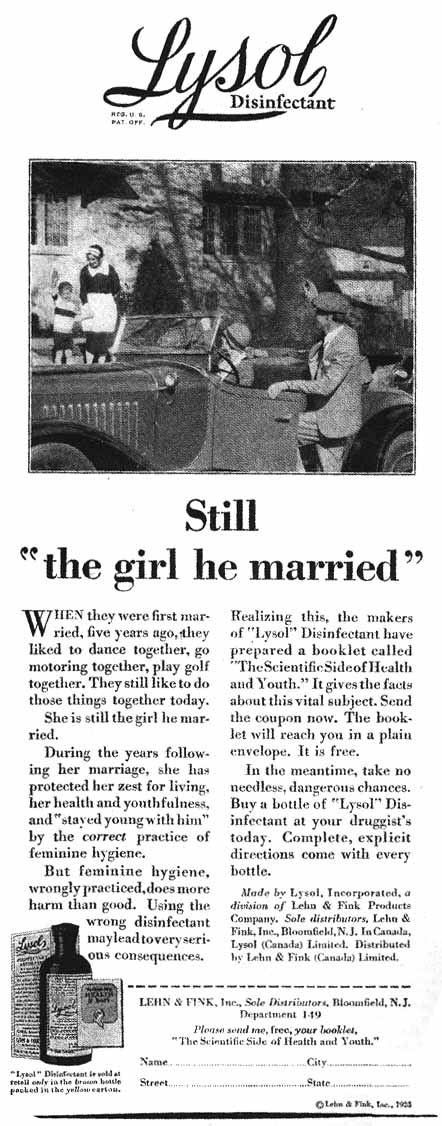

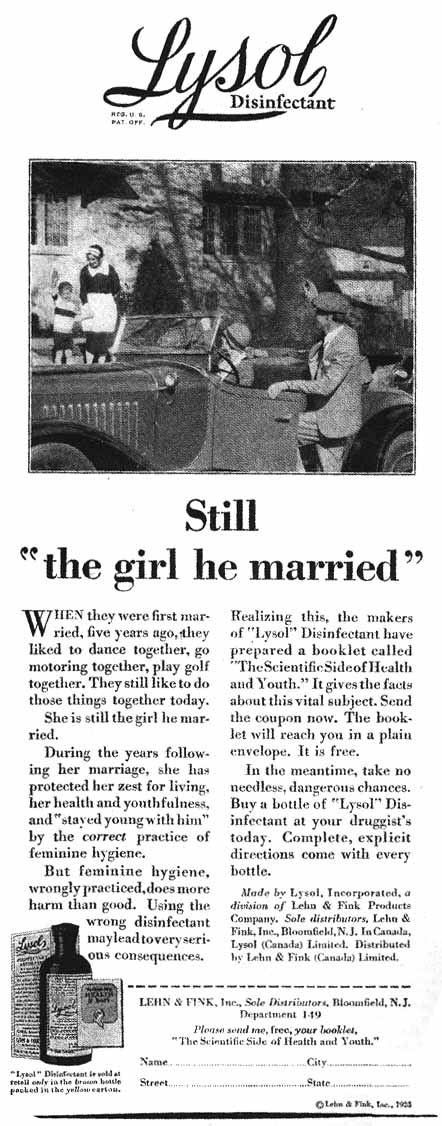

1920's Lysol Advertisement. Image @The Museum of Menstruation and Women's Health

More on the topic:

- Contraceptive sponge, Science Museum of London

- Kathleen London – History of Birth Control

- History of Contraception

- Condoms: History Hoydens

- Birth Control in the 18th Century: Catherine Delors

- Global Library of Women’s Medicine

- Campbell, Linda. Wetnurses in Early Modern England: Some Evidence from the Townshend Archive, Medical History 1989

- Constructions of Infanticide in Early Modern England: Female Deviance During Demographic Crisis, Sarah Cristine Shipley Copelan, 2008

- History of Condoms

- Safe Sex?

- Secret Sex Poems

- Hygienic Motherhood: Domestic Medicine and Eliza Fenwick’s Secrecy, Mercy Cannon, PDF Document, 2008

- Recommended reading: City of Laughter: Sex and Satire in Eighteenth-Century London, Vic Gatrell, 2006. ISBN 10 0 8027 1602 4

Read Full Post »