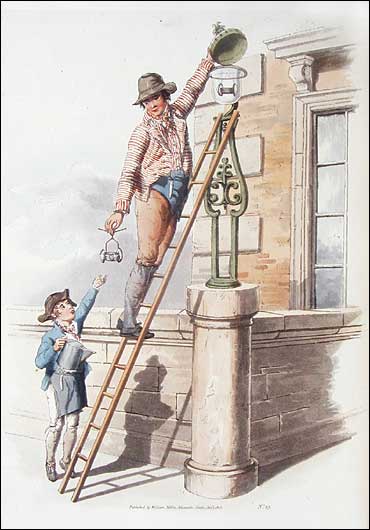

Lamplighter, Pyne, 1808

In Oxford Road alone there are more lamps than in all the city of Paris. Even the great roads, for seven or eight miles round, are crowded with them, which makes the effect exceedingly grand. – Archenholtz, 1780s

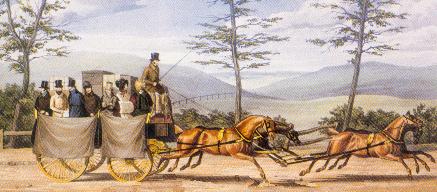

The Lamplighter, 1790's

Urban development in London grew at a rapid rate during the 18th century, especially in London’s West End, where the great squares were laid out. The population of London surpassed one million in 1815 and an increasing number of bridges were built between 1750 and 1819, boosting development south of the river. In 1750, a system of street lighting with oil lamps was introduced, changing the nature of city life. The lights were supplied with reflectors, a big improvement. Previous to 1736, the lights were lit until midnight, but after that year they stayed on until sunrise, making the streets safer. As the quote suggests, foreign visitors were impressed, for at that time no other city could boast of so much lighting. Before 1750, people who traveled at night hired link boys to light their way. Their torches emitted poor lighting, however, and the streets were dangerous and dark outside their small circles of light.

With the new system of lights, walking the streets at night became relatively safe. The new lights contributed to London’s nightlife and the sense that life in the City was unnatural and not subject to traditional constraints.* The pleasure gardens of London, such as Ranelagh and Vauxhall, offered illuminated entertainment, and fashionable people could travel to theatres, assembly rooms, and each others’ houses, which extended social interaction. Shops lighted window displays and stayed open later, profiting from the extended hours. The benefit of better lighting worked both ways, for:

The shop-keepers of London are of infinite service to the rest of the inhabitants by their liberal use of the Patent Lamp, to shew their commodities during the long evenings of winter. Anecdotes of the Manners and Customs of London During the Eighteenth Century, James Peller Malcolm, 1810, P 383,

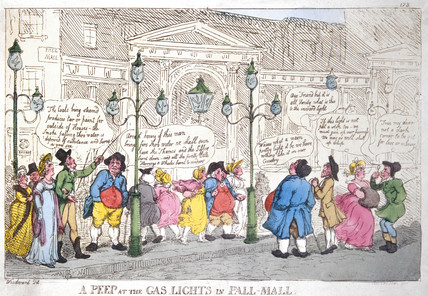

The first gas lights were introduced in Pall Mall on January 28th, 1807. Samuel Clegg had by then set up the London and Westminser Gas Lighting and Coke Company. On December 31, 1813, the Westminster Bridge was also lit by gas, and by 1823, 40,000 lamps covered 215 miles of London’s streets. Today, one can still see the gas lights in Green Park and the exterior of Buckingham Palace.

A peep at the gas lights in Pall Mall, Rowlandson

More on the topic:

- *The Archeology of Improvements in Britain, 1750-1850, Sarah Tarlow, p 101

- Time and Work in England 1750- 1830, Hans-Joachim Voth

- Gas Lamps in London

- Flickering Gas Light Illuminates Pall Mall