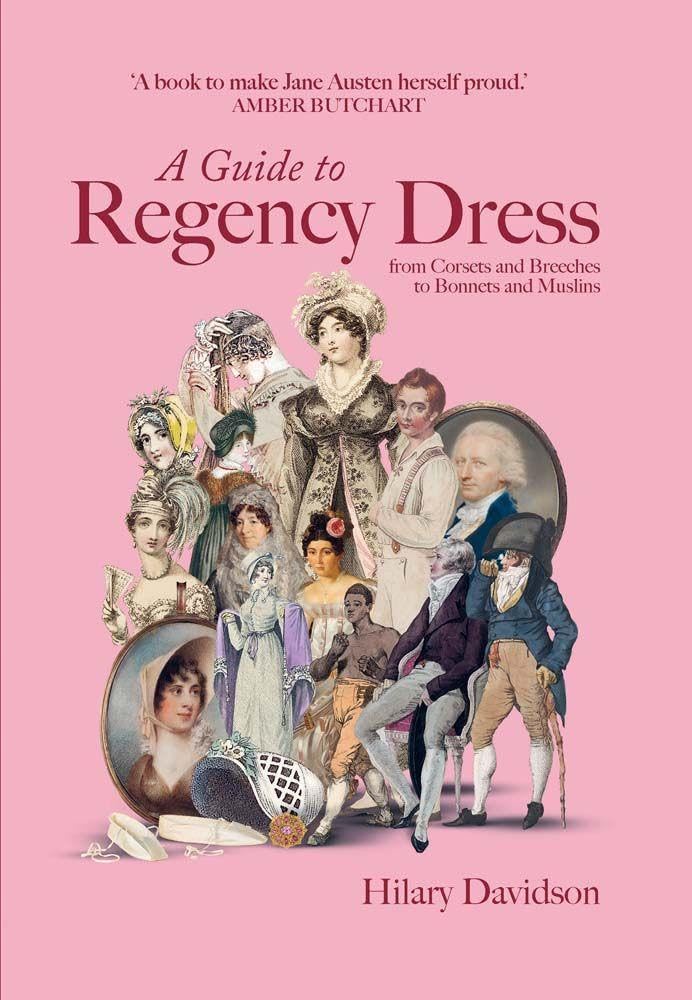

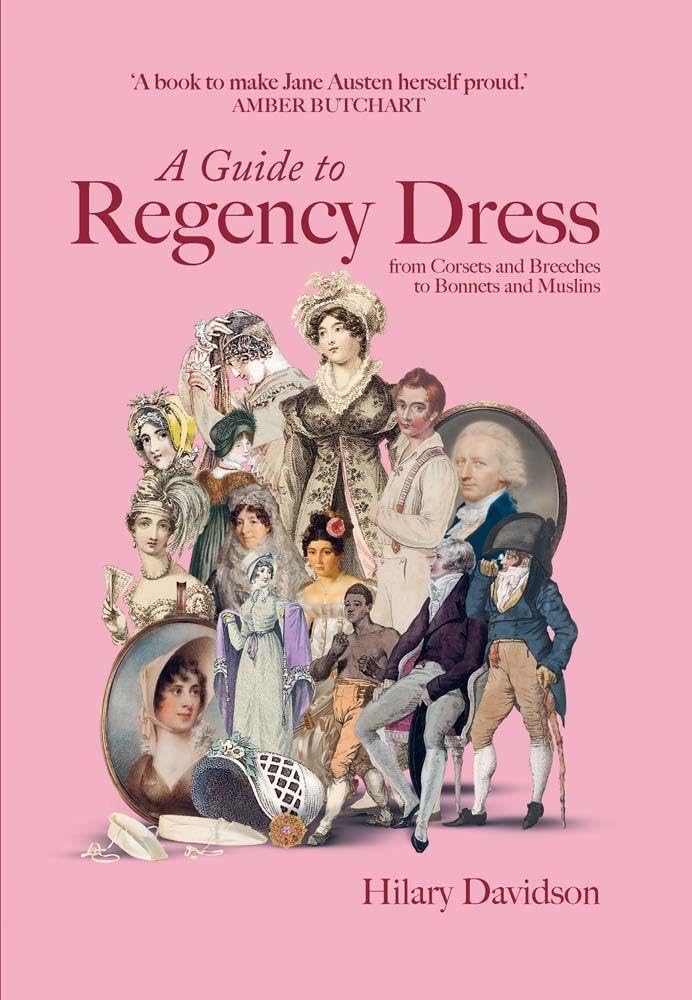

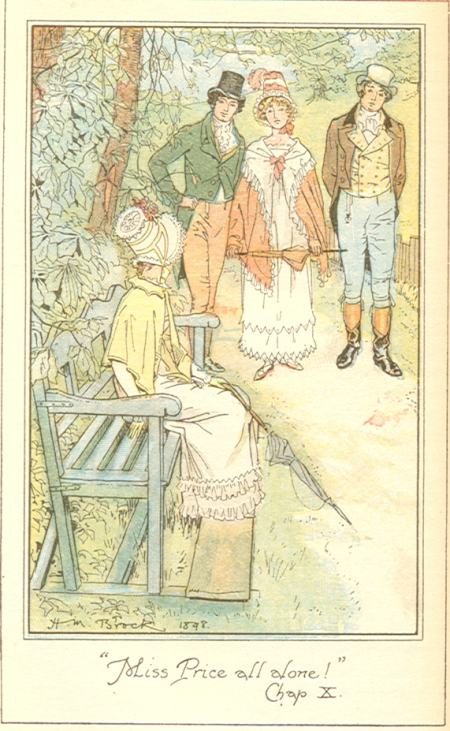

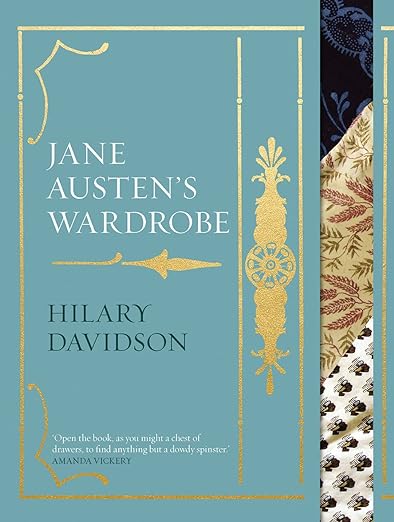

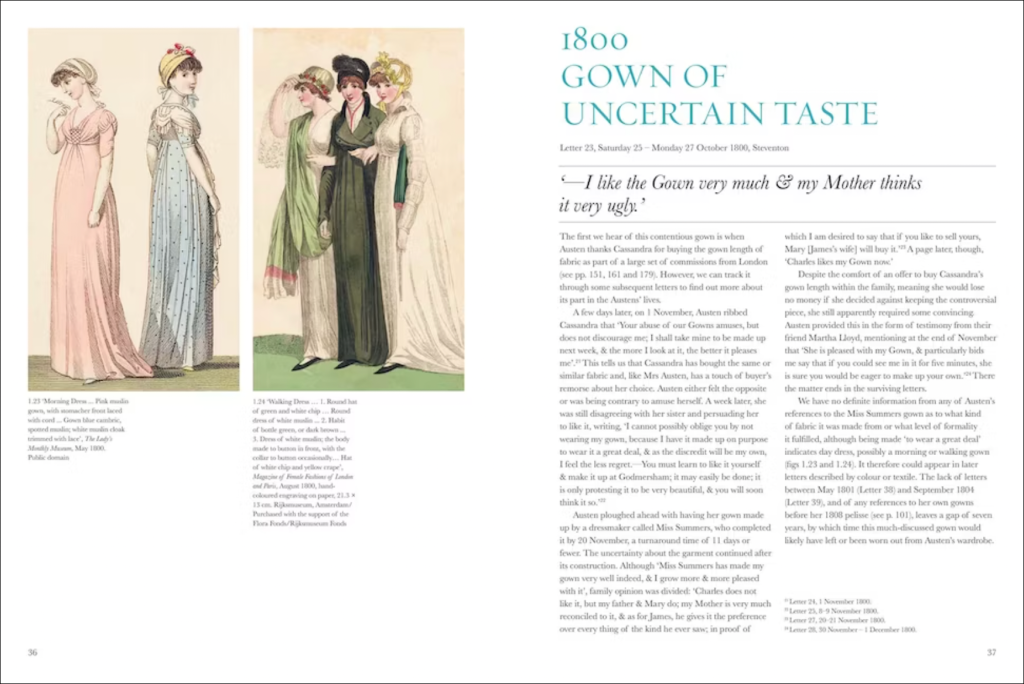

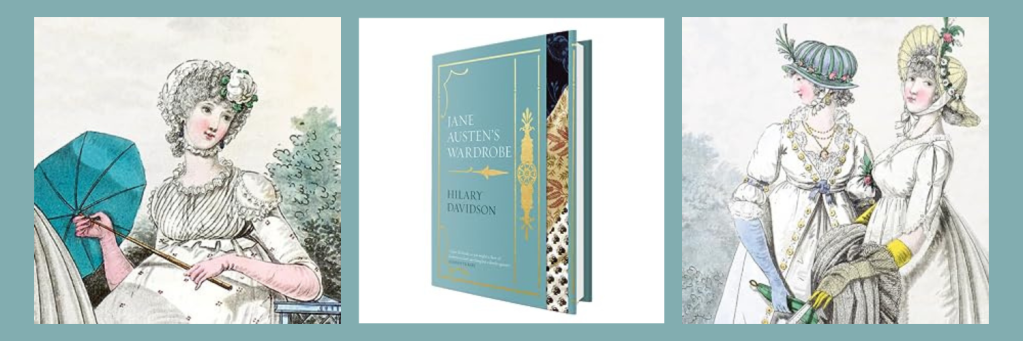

As we enter the new year, I introduce to you a beautiful new book by Hilary Davidson called A Guide to Regency Dress: from Corsets and Breeches to Bonnets and Muslins. This book is a true gem, and it was the perfect gift (to myself) for Christmas. I am a fashion and textiles nut, and a huge fan of Davidson’s work, including her previous book Jane Austen’s Wardrobe.

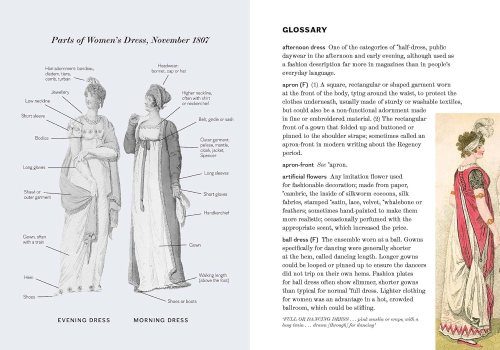

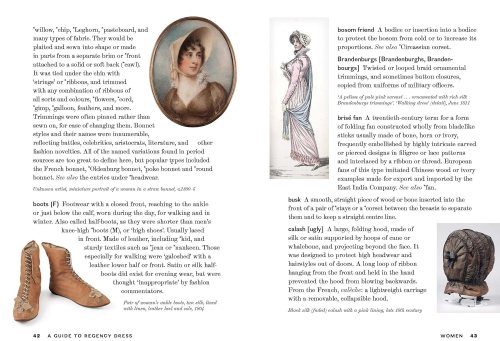

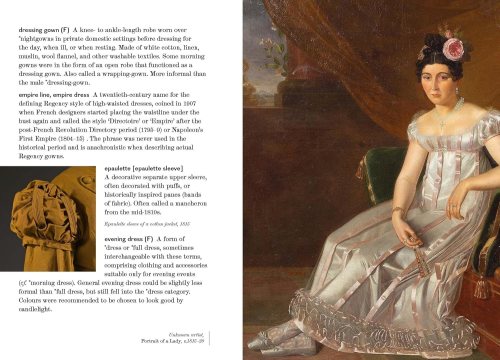

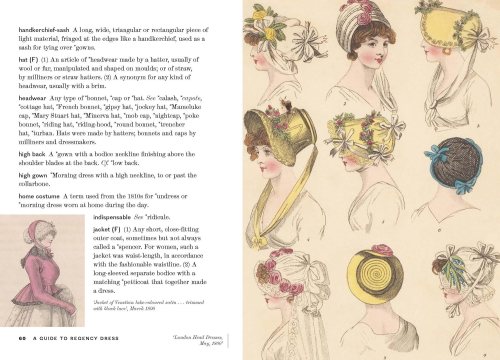

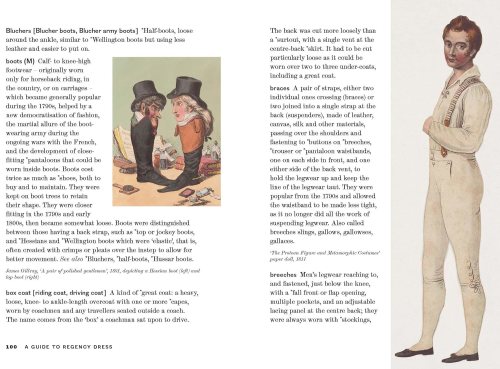

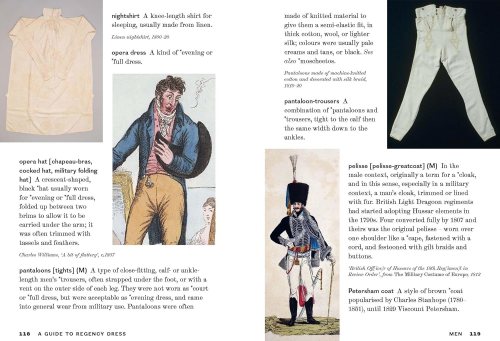

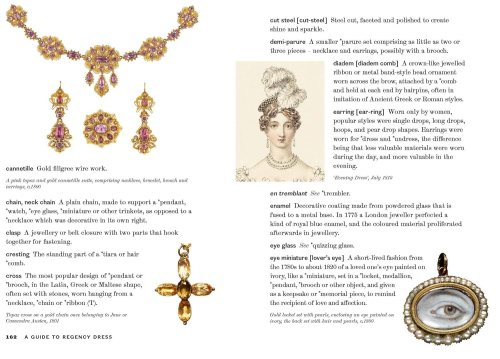

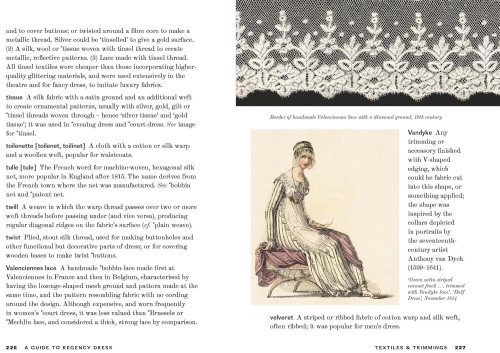

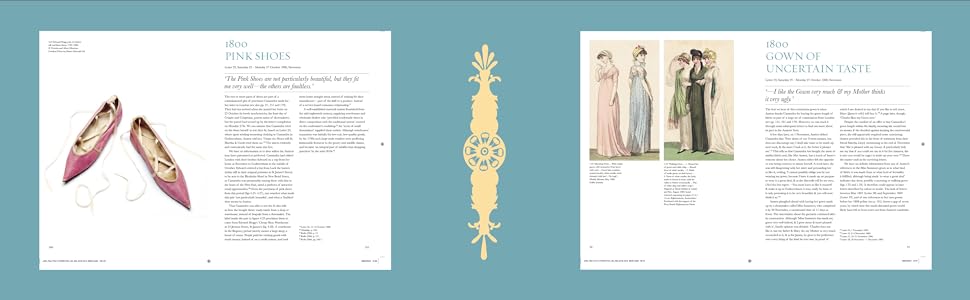

This is one of my favorite new books of the past year, and I plan to use it as I read and research Austen’s novels and watch the film adaptations. Davidson provides a comprehensive glossary of terms related to fashion and clothing during Austen’s time, included beautiful photography to help illustrate various items. Seeing everything in one place makes this a Jane Austen fashion dictionary and encyclopedia that is both fascinating and beautiful. What might normally take me hours to research for one of my articles, I can now find easily in one place.

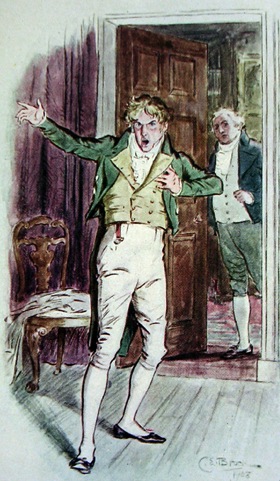

I particularly enjoyed the way the book is broken up into sections, with a detailed glossary in each section. The sections include Women, Men, Hair and Beauty, Jewellry (sic), and Textiles and Trimmings. Each section includes information and a full glossary with exquisite, full-color photos and illustrations. I enjoyed reading about the differences between items such as women’s stockings and men’s stockings. Women are often the focal point of Regency dress, but men’s clothing and dress is just as interesting. As a writer, I also appreciated Richardson’s extensive bibliography at the end of the book.

You can peruse this book anytime you want to learn more about dress in Austen’s day or find inspiration for your next Regency tea party, event, or ball!

Order Your Copy Here

About the Book

An accessible, fun, yet authoritative guide to male and female Regency fashion: Celebrated dress historian Hilary Davidson brings together nearly 20 years of research on Regency fashion in an illustrated guide for the first time. All the elements of the Regency wardrobe of both men and women―from coats, gowns and undergarments to shoes, accessories, beauty, hair and jewellery―are assembled, along with their textiles and trimmings.

A Guide to Regency Dress is an essential companion to navigate the fashion world of Jane Austen or re-create the Regency look. Here’s a look inside the book:

About the Author

Hilary Davidson is a dress, textiles, and fashion historian and curator. Hilary trained as a bespoke shoemaker in her native Australia before completing a Masters in the History of Textiles and Dress at Winchester School of Art (University of Southampton) in 2004. As a skilled and meticulous hand-sewer, she has created replica clothing projects for a number of museums, including a ground-breaking replication of Jane Austen’s pelisse.

In 2007, Hilary became curator of fashion and decorative arts at the Museum of London. She also worked on the AHRC 5-star rated Early Modern Dress and Textiles Network (2007-2009) and from 2011 has appeared as an expert on a number of BBC historical television programs, and as a frequent radio guest speaker in London and Sydney. From 2012, Hilary worked between Sydney and London as a freelance curator, historian, broadcaster, teacher, lecturer, consultant and designer, while working on a PhD in Archaeology at La Trobe University, Melbourne. In 2022, she moved to New York City to take up the role of Associate Professor and Chair of the MA Fashion and Textile Studies: History, Theory, Museum Practice at the Fashion Institute of Technology.

Hilary has taught and lectured extensively at the University of Southampton, Central St Martins, the University of Cambridge, the University of Glasgow, New York University London, The American University Paris, Fashion Design Studio TAFE Sydney and the National Institute of Dramatic Art, Sydney. Her previous books include Dress in the Age of Jane Austen (2019) and Jane Austen’s Wardrobe (2023).

Final Thoughts

When I attended my first JASNA AGM many years ago, I wore a beautiful Regency dress my mother sewed for me to the banquet and ball. I received a lot of compliments, but I only had a dress. Since then, I’ve slowly added to my “Jane Austen closet” with various accessories. Now that I have this book, I can continue to expand my collection until I can dress in Regency clothing from head to toe.

I could easily spend hours researching the fashion and textiles of Jane Austen’s era, and I hope others of you will find this new resource as fascinating as I do!

Rachel Dodge Bio

Rachel Dodge teaches writing classes, speaks at libraries, teas, and conferences, and writes for Jane Austen’s World blog. She is the bestselling, award-winning author of The Anne of Green Gables Devotional, The Little Women Devotional, The Secret Garden Devotional, and Praying with Jane: 31 Days Through the Prayers of Jane Austen. She has narrated numerous book titles, including the Praying with Jane Audiobook with actress Amanda Root. A true kindred spirit at heart, Rachel loves books, bonnets, and ballgowns. Visit her online at www.RachelDodge.com.