Chelsea Buns. Image courtesy @Kathleen Corfield, The Ordinary Cook (Click on blog for the British recipe.)

Our crocuses and daffodils are blooming in Richmond, making me realize that Easter and spring and hot cross buns are just around the corner. Back in Jane Austen’s day, the Chelsea bun was the treat of choice. These sticky sweet buns, filled with raisins and currants and topped with a sugary glaze, were sold by the tens of thousands at the famous Chelsea Bun-House on Pimlico Road near Sloane Square in London (technically Pimlico, not Chelsea), which was frequented by Royalty and the public alike.

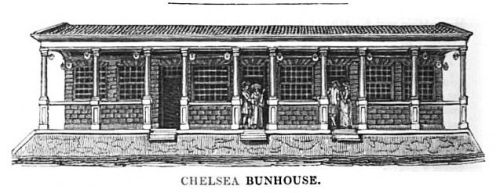

During the last century, and early in the present, a pleasant walk across green fields, intersected with hedges and ditches, led the pedestrian from Westminster and Millbank to “The Old Bun House” at Chelsea. This far-famed establishment…stood at the end of Jew’s Row (now Pimlico Road), not far from Grosvenor Row. The building was a one-storeyed structure, with a colonnade projecting over the foot pavement, and was demolished in 1839, after having enjoyed the favour of the public for more than a century and a half. ” – Old and New London: Volume 5, Edward Walford, 1878, British History Online, Chelsea

“I soon turned the corner of a street which took me out of sight of the space on which once stood the gay Ranelagh. … Before me appeared the shop so famed for Chelsea buns, which for above thirty years I have never passed without filling my pockets. In the original of these shops—for even of Chelsea buns there are counterfeits—are preserved mementoes of domestic events in the first half of the past century. The bottle-conjuror is exhibited in a toy of his own age; portraits are also displayed of Duke William and other noted personages; a model of a British soldier, in the stiff costume of the same age; and some grotto-works, serve to indicate the taste of a former owner, and were, perhaps, intended to rival the neighbouring exhibition at Don Saltero’s. These buns have afforded a competency, and even wealth, to four generations of the same family; and it is singular that their delicate flavour, lightness, and richness, have never been successfully imitated.” – Sir Richard Phillips, “Morning’s Walk from London to Kew,” 1817.

Chelsea Bun-House image from The Mirror, Google eBook

The building was fifty-two feet long, by twenty-one feet wide. The colonnade e xtended over the foot pavement into the street, and afforded a tempting shelter and resting-place to the passenger to stop and refresh himself. Latterly the floor of the colonnade was level with the road, which has probably been considerably raised; as in the old print it is represented as a platform with steps at the three doors for company to alight from their carriages. – The Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Chronicle, Volume 11, 1839

Not all of the bun house’s customers enjoyed the sweet sticky buns, as Dean Swift attests in 1711: “Pray, are not the fine buns sold here in our town? was it not R-r-r-r-r-r-r-r-r-rrare Chelsea buns ? I bought one today in my walk ; it cost me a penny ; it was stale, and I did not like it, as the man said, [R-r-r-r-rnre] Sec.” – (Journal to Stella. May 2, 1711.)

It is not to be wondered at, that the witty Dean did not relish his stale bun ; for, to be good, it should be made with a good deal of butter, be very light, and eat hot. Chelsea Buns formed a frequent cry in the streets of London during the last century, and were as popular as the Bath Buns of the present time. The cry (or rather song) was ” Chelsea Buna, hot Cheheii Buns, rare Chelsea Buns! ” Good Friday was the day in all the year when they were most in request; and the crowds that frequented the Bunhouse on that day, is almost past belief. – Gentleman’s Magazine

The following account was written in The Mirror, April 6, 1839, the year that the original Bun-House was demolished for improvements.

CHELSEA BUN-HOUSE. This Bun-House, whose fame has extended throughout the land, was first established about the beginning of the last century; for, as early as 1712, it is thus mentioned by the celebrated Dean Swift:—”Pray are not the fine buns sold here in our town, as the rare Chelsea buns ? I bought one to-day in my walk,” &c.

The building consists of one story, fifty feet long, and fourteen feet wide. It projects into the high-way in an unsightly manner, in form of a colonade, affording a very agreeable shelter to the passenger in unfavourable weather.

The whole premises are condemned to be pulled down immediately, to make way for the proposed improvements of Chelsea and its neighbourhood, the bill for which is in committee of the House of Commons, under the superintendance of that most active member, Sir Matthew Wood.

It was the fashion formerly for the royal family, and the nobility and gentry, to visit Chelsea Bun-House in the morning. His Majesty King George the Second, Queen Caroline, and the Princesses, frequently honoured the elder Mrs. Hand with their company.

Their late Majesties King George III, and Queen Charlotte, were also much in the habit of frequenting the Bun-House when their children were young, and used to alight and sit to look around and admire the place and passing scene. The Queen presented Mrs. Hand with a silver half-gallon mug, richly enchaced, with five guineas in it, as a mark of her approbation for the attentions bestowed upon her during these visits: this testimonial was kept a long time in the family.

On the morning of Good Friday, the Bunhouse used to present a scene of great bustle; it was opened as early as four o’clock j and the concourse of people was so great, that it was difficult to approach the house; it has been estimated that more than fifty thousand persons have assembled in the neighbourhood before eight in the morning; at length it was found necessary to shut it up partially, in order to prevent the disturbances and excesses of the immense unruly and riotous London mob which congregated on those occasions. Hand-bills were printed, and constables stationed to prevent a recurrence of these scenes.

Whilst Ranelagh was in fashion, the BunHouse was much frequented by the visitors of that celebrated temple of pleasure ; but after the failure of Ranelagh, the business fell off in a great degree, and dwindled into insignificance.

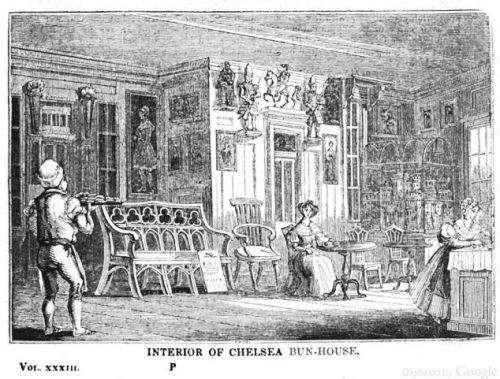

Interior of Chelsea Bun-House. Image from 1839 edition of The Mirror, Google eBook. The inside of the Bun-House was fitted up as a museum. It might have contained some very curious articles, but the most valuable had long since disappeared.The materials of the building, with the relics of the museum, were sold by auction April 18, 1839, and the whole was immediately cleared away. – Gentleman’s Magazine

Click here to see a color drawing of the Bun-House interior at the British Museum

See another image of the Bun-House at Swann Galleries

INTERIOR Of CHELSEA BUN-HOUSE. The interior was formerly fitted up in a very singular and grotesque style, being furnished with foreign clocks, and many natural and artificial curiosities from abroad ; but most of these articles have disappeared since the decease of Mrs. Hand.

At the upper end of the shop is placed, in a large glass-case, a model of Radcliffe Church, at Bristol, cut out very curiously and elaborately in paste-board ; but the upper towers, pinnacles, &c. resemble more an eastern mosque than a Christian church.

Over the parlour door is placed an equestrian coloured statue, in lead, of William, the great Duke of Cumberland, in the military costume of the year 1745, taken just after the celebrated battle of Culloden: it is eighteen inches in height.

On each side stand two grenadier guards, presenting arms, and in the military dress of the above period, with their high sugarloaf caps, long-flap coats, and broad gerilles, and old-fashioned muskets, presenting a grotesque appearance, when compared with the neat short-cut military trim of the present day. These figures are also cast in lead, and coloured; are near four feet high, and weigh each about two hundred weight.

Underneath, on the wall, is suspended a whole-length portrait, much admired by connoisseurs, of Aurengzebe, Emperor of Persia. This is probably the work of an Italian artist, but his name is unknown.

After the death of Mrs. Hand, the business was carried on by her son, who was an eccentric character, and used to dress in a very peculiar manner,; he dealt largely in butter which he carried about the streets in a basket on his head; hot or cold, wet or dry, throughout the year, the punctual butterman made his appearance at the door, and gained the esteem of every one by his cheerful aspect and entertaining conversation ; for he was rich in village anecdote, and could relate all the vicissitudes of the neighbourhood for more than half a century.

After his decease, his elder brother came into the possession of the business; he had been bred it soldier, and was at that time one of the poor knights of Windsor, and was remarkable for his eccentric manners and costume. He left no family, nor relations, in consequence of which his property reverted to the crown…A writer in the Gentleman’s Magazine, vol. LIU. for July 1783, p. 578, speaking of Cross Buns in Passion week, observes, that ” these being, formerly at least, unleavened, may have a retrospect to the unleavened bread of the Jews, in the same manner as Lamb at Easter to the Pascal Lamb. “

Chelsea Bun-House, image @ Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Chronicle, Volume 11. One can see the raised steps leading to three doors where ladies and gentlemen could alight comfortably from their carriages.

Apparently when Chelsea Buns were invented there were two rivals who vied for the honor of selling the best buns: the Old Chelsea Bun House or the “Real Old Original Chelsea Bun-house.” On Good Friday, long lines of people waited to purchase the buns. In 1792, the Good Friday line was so long that the Bun-House skipped selling them the following year. A notice stated:

“Royal Bun House, Chelsea, Good Friday.—No Cross Buns. Mrs. Hand respectfully informs her friends and the public, that in consequence of the great concourse of people which assembled before her house at a very early hour, on the morning of Good Friday last, by which her neighbours (with whom she has always lived in friendship and repute) have been much alarmed and annoyed; it having also been intimated, that to encourage or countenance a tumultuous assembly at this particular period might be attended with consequences more serious than have hitherto been apprehended; desirous, therefore, of testifying her regard and obedience to those laws by which she is happily protected, she is determined, though much to her loss, not to sell Cross Buns on that day to any person whatever, but Chelsea buns as usual.”

Forty six years later, the Bun-House closed its doors for good. One has to wonder today if during her many trips to London Jane Austen traveled to the Bun-House on Pimlico Road to purchase a half-dozen of these fresh-baked delicacies.

Read more on the topic:

- Chelsea Buns: CooksInfo.com

- The Mirror, April 6, 1839: The Chelsea Bun-House

- Gentleman’s Magazine

- The Old Chelsea Bun Shop

- British History Online

- The Old Chelsea Bun-House, eBook, Mary Powell, 1855

- An Englishman’s Favorite Bits of England

- Baking for Britain

- The Old Chelsea Bun House: A taste of the last century (1855)