By Brenda S. Cox

“Yesterday came a letter to my mother from Edward Cooper to announce, not the birth of a child, but of a living; for Mrs. Leigh has begged his acceptance of the Rectory of Hamstall-Ridware in Staffordshire, vacant by Mr. Johnson’s death. We collect from his letter that he means to reside there, in which he shows his wisdom. Staffordshire is a good way off . . .”—Jane Austen to Cassandra, Jan. 21, 1799

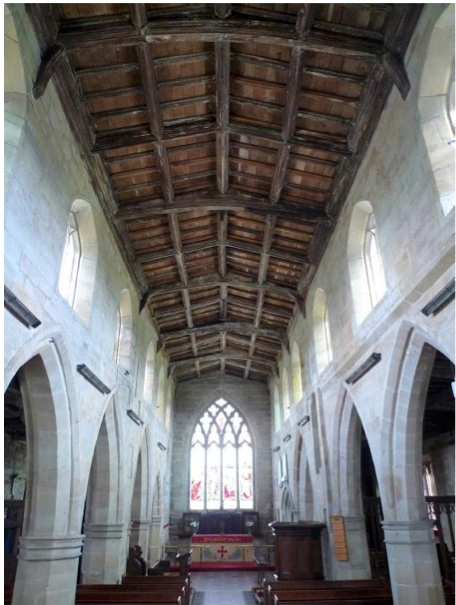

In 1806, Jane Austen and her family made a trip to visit their relatives in the north. They spent five weeks with her first cousin Edward Cooper, rector of Hamstall Ridware (whom I wrote about earlier). They stayed in his rectory, and must have attended the adjacent Church of St. Michael and All Angels and heard Edward Cooper preach there. The church is still much as Austen knew it, inside and out.

Hamstall Ridware History

Hamstall Ridware means “homestead,” or “place of the house,” by the “river ford.” It is on the River Blithe. The first word is Anglo-Saxon, the second is Celtic, indicating that the two people groups may have both been living in the area at the time it was named. Three other towns with the name Ridware (Pipe Ridware, Hill Ridware, and Mavesyn Ridware) are nearby.

The de Ridware family were the medieval “lords of the manor” for the area. The church was built, in the Norman style, around 1120 A.D, and expanded in the 14th and 15th centuries.

In the 1370s, the de Ridwares had no male heir, so the land passed to the Cotton family. A Cotton family tomb, from the time of King Henry VIII, still stands in the church. Each shield on the sides commemorates one of the children of John and Joanna Cotton. Half of each shield is their family crest, an eagle on a blue background. For the sons, the other half represents their profession. For the daughters, the other half shows the shield of their husband’s family.

In the 1500s, the Cottons had no male heir, so the manor, Hamstall Hall, and the lands, passed to Sir Anthony Fitzherbert, the husband of the eldest daughter.

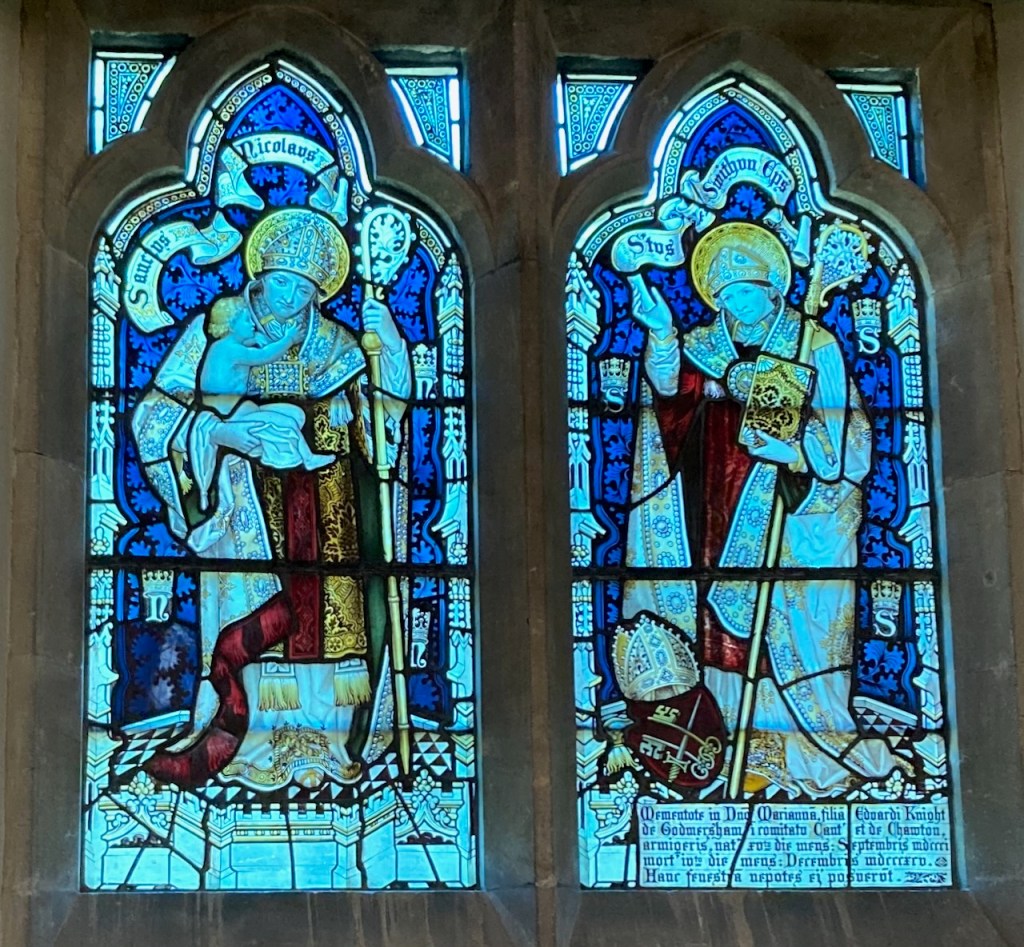

In 1601 the estate went to Sir Thomas Leigh of Stoneleigh, one of Jane Austen’s forebears. This early stained glass window, incorporating 14th century glass, commemorates all these patrons of the Hamstall Ridware church. Each family would have owned the advowson for the Hamstall Ridware church, the right to choose the rector of the church when the previous one died.

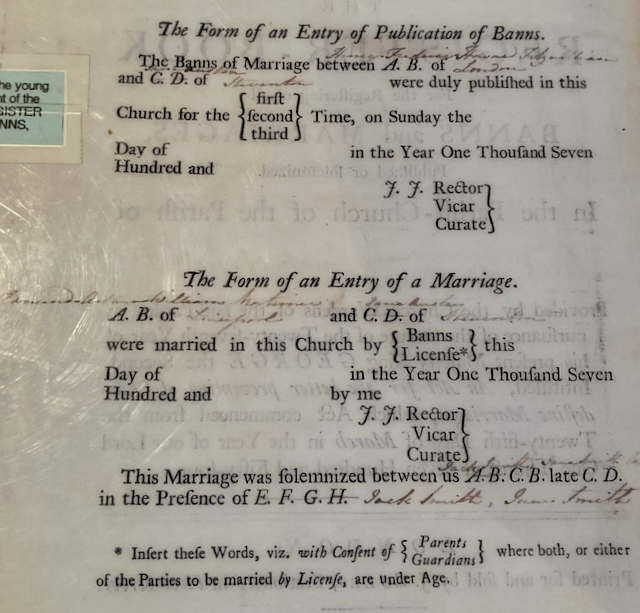

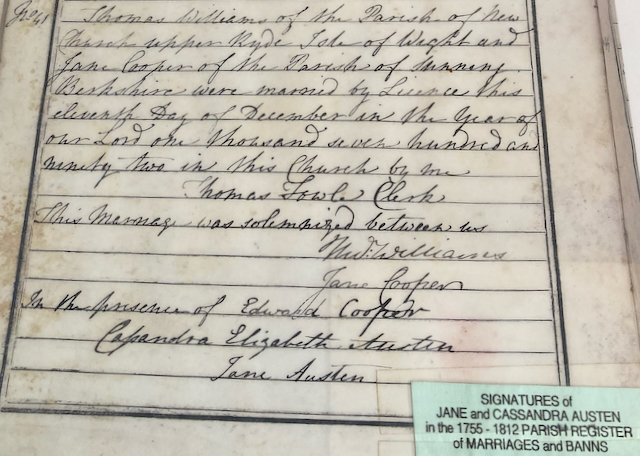

The Leighs’ main home was at Stoneleigh Abbey (which we’ll “visit” later). The Hon. Mary Leigh of Stoneleigh Abbey was patroness of Hamstall Ridware in 1799. When the previous rector, Mr. Johnson, died, she gave the living to her relative Edward Cooper. Before that he had been a curate, an assistant or substitute clergyman, probably with a low salary, at Harpsden. Jane and her family had visited the Coopers at Harpsden in August and September of 1799, before the Coopers moved to Hamstall Ridware in October. Edward invited them to visit Hamstall Ridware in 1801, but Jane said in a letter that they preferred to go to the seaside that summer. However, five years later, the Austens did make a long trip to visit their Leigh relations at Adlestrop, then accompanied their cousin, Rev. Thomas Leigh, who had just inherited Stoneleigh Abbey, to the abbey. From Stoneleigh they went to Hamstall Ridware, 38 miles away.

During this time, it’s possible that Jane may have seen the play Lover’s Vows, an important part of Mansfield Park. It was advertised in a village called Cheadle about an hour’s carriage ride away (Gaye King, “Visiting”).

Unfortunately, during Jane’s visit, Edward’s eight children came down with whooping cough, and Jane got it a few weeks later, after she got home (Letters, Jan. 7, 1807).

The Rectory

The rectory (or parsonage, the house provided for the rector of the parish) where the Austens stayed is now a private home. It is now difficult to see even from the outside, but this photo shows the building before a gate was built.

It has been speculated that this rectory was the pattern for the Delaford rectory, where Edward and Elinor Ferrars settle in Sense and Sensibility. The layout of the Delaford estate, with “stew-ponds” (fish ponds), “a very pretty canal” (perhaps suggested by the nearby river), and “great garden walls,” also corresponds to some features of the Leighs’ estate at Hamstall Ridware.

“Edward had found the rectory quite large enough to accommodate his growing family. Like the fictional parsonage at Delaford it had ‘five sitting-rooms on the ground floor, and … could make up fifteen beds’ (292). So the young rector could look forward to maintaining the tradition of liberal hospitality such as that he had enjoyed at the Steventon parsonage. When Jane Austen, together with her mother and sister, did eventually spend those five weeks at Hamstall Ridware in 1806 Edward and Caroline had eight children. There were also, living in at the rectory, two maids and a governess, yet there was still ample accommodation for the guests.”

(I have since noticed that the five sitting rooms and fifteen beds were characteristics of the manor house where Col. Brandon lived, not of the parsonage! And I doubt a country parsonage would have so many sitting rooms.)

However, relatives who visited wrote that it was “a beautifully situated parsonage house on a considerable eminence, back’d with fine woods, seen at a distance from the road to this happy village,” and that the church “was a very neat old Spire Building of stone, having two side Ailes [sic] Chancel &c. and makes a magnificent appearance as a Village Church” (quoted in Deirdre Le Faye, Jane Austen: A Family Record, 157).

The Church of St. Michael and All Angels, Hamstall Ridware

The church is large, seating 200 people, almost three times the size of Jane’s church at Steventon (which seats about 75). It has a long central aisle leading to the chancel, where the altar sits, and two side aisles. Lining both sides is a clerestory, high walls with a series of windows which let in natural light.

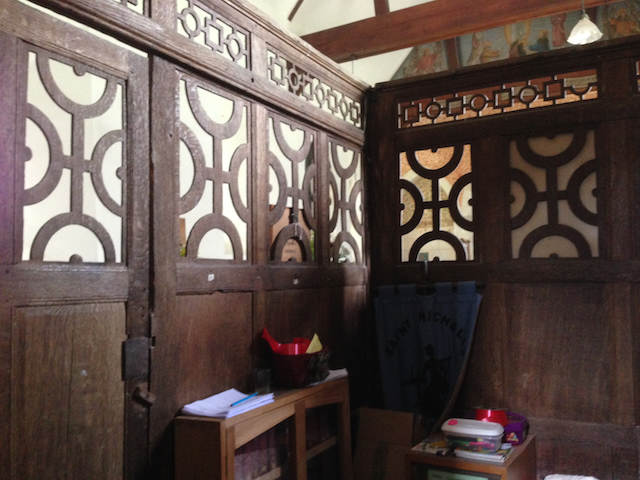

Like many churches in England before the Reformation, this church once had a rood screen separating the chancel from the nave. This was a barrier between the chancel, where the clergy celebrated mass at the altar, and the lay people worshiping in the nave. It was usually topped by a cross; the Anglo-Saxon word for cross is rood. Some churches also had a rood loft, above the screen, from which a choir would sing parts of the service. Many rood screens and lofts were destroyed during or after the Reformation, to symbolize people’s more direct access to God.

A few steps, which once led to the rood loft, still remain in one wall. Two paintings from the rood screen are now behind the main altar in a reredos (reer-ih-dahss is one pronunciation). This means a decorative panel behind the altar. These paintings are from the late 15th century, by an unknown accomplished artist, probably local.

Memorials to the Cooper Family

Edward Cooper and his family left their mark on the church. The memorial to Edward Cooper says:

In a vault near this spot, are deposited the remains of the Rev. EDWARD COOPER, who, for upwards of 30 years was rector of this parish, and for many years of the adjoining parish of Yoxall also: in both which places, (as a faithful minister of Christ, and endeared to all his parishioners,) he discharged, with unremitting zeal, the duties of his sacred office.

He was the only son of the Rev. Edward Cooper, L.L.D. vicar of Sonning Berks, &c. and prebendary of Bath and Wells; and of Jane his wife, grandaughter of Theophilus Leigh, Esq., of Addlestrop, in the county of Gloucester,

He was formerly fellow of All-Souls’ College, Oxford, as was his father also.

He departed this life, the 26th day of February, 1833, in the 63rd year of his age.

“He being dead yet speaketh”

Within the same vault also repose the remains of CAROLINE ISABELLA, his widow, only daughter of Philip Lybbe Powys, Esq. of Hardwick House in the county of Oxford,

She died on the 28th day of August, 1838, in the 63rd year of her age.

This tablet is erected by their eight surviving children, as a tribute of grateful affection, and respect, to the memory of their deeply lamented, and much beloved parents.

As the memorial notes, Edward was also rector of a neighboring parish, Yoxall (from 1809). Like George Austen, he needed the income from two small parishes and was able to serve them both since they were close. Rev. Thomas Gisborne, another Evangelical minister, was from Yoxall. He wrote a book that Cassandra and Jane both liked, An Enquiry into the Duties of the Female Sex (letter of Aug. 30, 1805). Perhaps Edward had recommended it to them. Though we have no record of it, it’s possible Jane could have met Gisborne during her visit. He was a friend of Edward’s, and he and Henry Austen were the godfathers of one of Edward’s sons. Gisborne was also involved with Wilberforce in fighting the slave trade. (Gaye King, “Cousin” article)

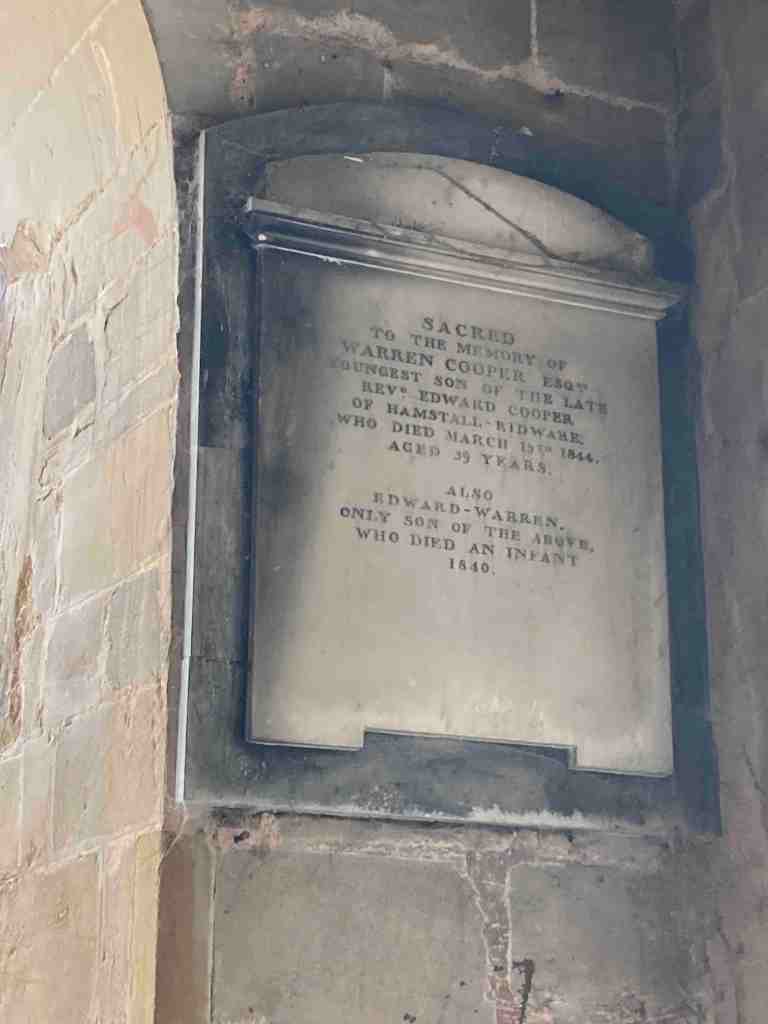

On another wall is a memorial to Edward’s son and grandson. His youngest son Warren died in 1844, age 39, and Warren’s son, Edward-Warren, died as an infant in 1840.

Outside, under a large cross, are the graves of Edward’s third son, Rev. H. C. Cooper, vicar of Barton-under-Needwood (5.6 miles away), who died in 1876, “in the 76th year of his age.” Also Edward’s second daughter, Cassandra Louisa, who died in 1880, “in the 84th year of her age.” The final inscription reads, “Looking for the mercy of our Lord Jesus Christ unto eternal life. Jude, v. 21”

Another side memorializes Frederic Leigh Cooper, born 1801, died 1885. This was Edward’s fifth child.

Glebe

Green fields surround the church. Most churches in England had glebe land, farmland that provided income for the clergyman. In 1978, all glebe land was transferred to the dioceses, who administer it now. (A diocese is a group of church parishes overseen by a bishop.) Some modern locations in England still retain the name glebe. Hamstall Ridware is part of the Diocese of Lichfield, and I was told the diocese still receives income from grazing on glebe lands nearby. Glebe income today is used to pay clergy salaries and other expenses.

The Church Today

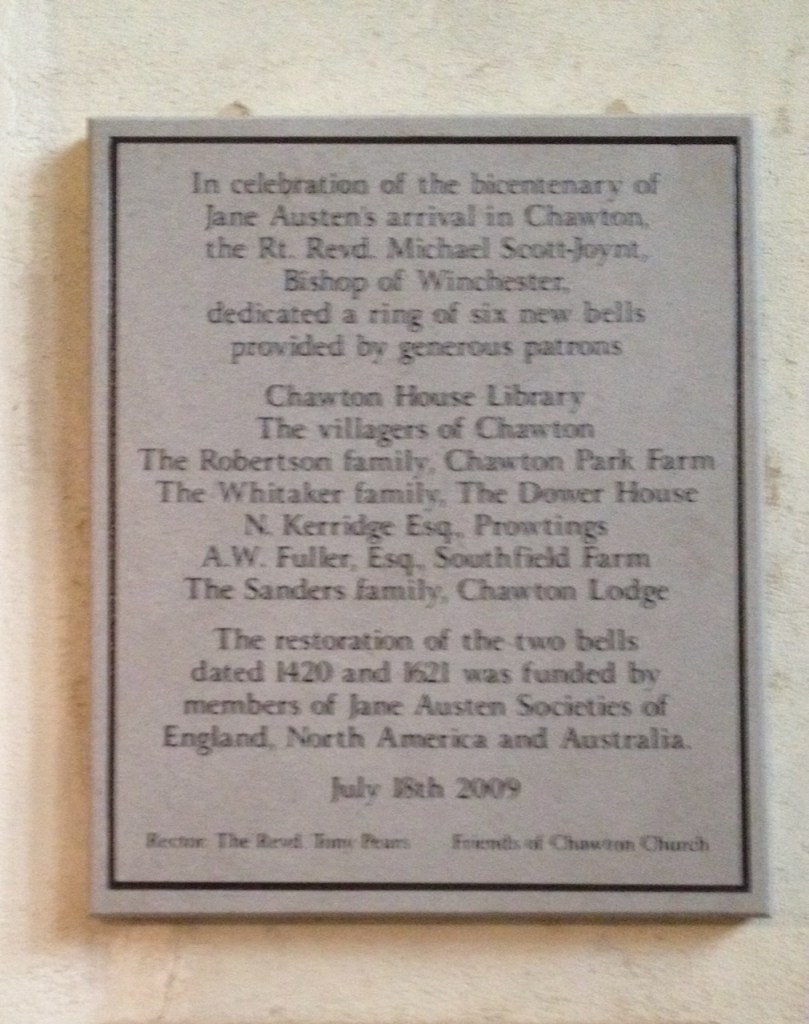

The Hamstall Ridware church is now part of a benefice including four parishes with one rector. In 1831, the population of the parish was 443. In 2011 it was 313.

Hamstall Hall, previous home of the Leigh family, is now mostly in ruins. But, according to the church booklet, the current Lord Leigh is still “a patron of the United Benefice of King’s Bromley, the Ridwares, and Yoxall jointly with the Bishop of Lichfield and the Dean and Chapter of Lichfield Cathedral.” (In other words, they jointly choose/approve the clergymen for the churches of the benefice.)

Like Chawton and Steventon, Sunday services are held at the Hamstall Ridware church weekly, usually with only ten or so faithful parishioners attending. The church is large, seating 200 people, but it has little heating, and only a chemical toilet outside. However, they do get big crowds for Harvest, Christmas, and other special services, as well as lectures and concerts. And many visitors come to the church, which is open in the daytime, though apparently the door can be tricky to open.

The Church of St. Michael and All Angels is well worth a visit for Jane Austen enthusiasts. It is just over an hour’s drive, by car, from Stoneleigh Abbey. The Samuel Johnson Birthplace Museum in Lichfield is on the way.

For Further Exploration

This post from the Ridware Historic Society includes diary entries from Edward’s mother-in-law, during her visits to the family at Hamstall Ridware, as well as more information about the town and its people.

The church website gives some history and a schedule of services.

The historic listing tells more details of the church’s architecture.

A video showing many aspects of the church

Booklet on the church (a slightly older version than the one I used for this article)

Photos on Flickr of Hamstall Hall, Hamstall Ridware church and Yoxall church

Gaye King “Jane Austen’s Staffordshire Cousin: Edward Cooper and His Circle,” Persuasions 1993

Gaye King, “Visiting Edward Cooper,” Persuasions 1987

Donald Greene article, “Hamstall Ridware: A Neglected Austen Setting,” Persuasions 1985

Posts on other Jane Austen Family Churches

Adlestrop and the Leigh Family

Great Bookham and Austen’s godfather, Rev. Samuel Cooke

Ashe and Jane’s Friend Mrs. Lefroy

Brenda S. Cox is the author of Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England. She also blogs at Faith, Science, Joy, and Jane Austen.