“My father’s old Ministers are already deserting him to pay their court to his Son; the brown Mare, which, as well as the black was to devolve on James at our removal, has not had patience to wait for that, & has settled herself even now at Deane.”—Jane Austen to Cassandra, Jan. 8, 1801, when her brother James was about to take over their father’s place as clergyman at Steventon church (as his father’s curate), and James was taking over much of their property as Jane, Cassandra, and their parents moved to Bath.

Church was an important part of Jane Austen’s life and her family’s lives. Last time we explored the church at Chawton, which Austen attended during the later years of her life. Today we’ll visit Steventon, the church in which she grew up. Both churches are named after St. Nicholas, both are small country churches of the national Church of England, and both are named after St. Nicholas, patron saint of sailors, children, and others. (He is also called, in a more modern incarnation, Santa Claus.)

The Rectory

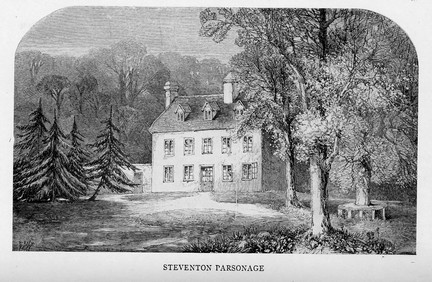

Jane grew up in the rectory at Steventon, which no longer exists. Her father was the rector, the clergyman of St. Nicholas’. The rectory, or parsonage, was the house provided for the rector to live in. George Austen made repairs and additions to the rectory as his family grew, and as he began to teach boarding students to supplement his church income.

When Jane’s father died in 1805, her brother James became rector of Steventon. After he died, her brother Henry served temporarily for three years (as Charles Hayter gets a temporary living at the end of Persuasion). Both lived in the rectory while serving the church.

However, that rectory was damp and tended to flood. The Knight family were the patrons of the parish, choosing the rectors for the church (as Colonel Brandon was the patron of his parish, giving a church living to Edward Ferrars). In 1823, Edward Knight’s son William Knight (Jane’s nephew) became rector of Steventon. Edward built a new rectory for his son, opposite the church on higher ground. That building still stands, now a private home called Steventon House (put up for sale in 2023).

Jane Austen’s family home, the old rectory, was demolished in the 1820s. In 2011, excavators found bits and pieces at the site: fragments of pottery and crockery, nails, etc. An old pump sat on the site for a long time; now you can see part of it inside the church.

The church itself is still standing and, in form at least, is mostly as Jane Austen knew it. She and her family worshiped there most Sundays for the first twenty-five years of her life. They likely attended church on Sunday afternoons or evenings as well as mornings. Services were several hours long, so Jane spent quite a bit of time at that church.

History of St. Nicholas’ Church, Steventon

Steventon was apparently a place of Christian worship from a very early date. Part of the shaft of a Saxon Cross, from about the ninth century, was discovered built into the wall of a nearby Tudor manor (now demolished). The cross shaft is displayed in the church. The cross was likely set up outdoors. Visiting priests would hold services there, before the church was built. Villagers may also have buried their dead near the cross. Steventon was possibly a stop on the Salisbury to Canterbury pilgrimage route.

The church building is medieval, built around 1200 A.D. The most obvious change since Jane Austen’s time is the addition of a Victorian steeple (around 1850-1860), a blue and brown structure that looks quite different from the rest.

Jane would have seen the four ancient “scratch dials” or “Mass clocks” on the outside walls of the church. These were sundials with a scratch marking the time when people were to come to worship. She would have also seen the medieval carvings of faces, a man and a woman, on either side of the main door.

Next to the church is a gigantic yew tree, an estimated 900 years old. It measures at least 25 feet around. Yews were considered sacred in ancient times and also by Christians. They represented regeneration and new life. The church key, 15 inches long and weighing 5 lb., was kept in a hole in this tree during Austen’s time. After the key disappeared, a replacement was made which is kept elsewhere. The church is now always left unlocked for visitors.

The tower holds three church bells. The oldest was cast in 1470. These bells were restored, through the support of JASNA, in 1995. I got to hear them ringing when the JASNA Summer Tour group visited in July. The bells are rung for church services, weddings, and funerals.

The Church Interior

The layout of the church is still much the same as it was in Jane Austen’s time. Three arches separate the nave of the church (where the congregation sits) from the chancel (where the altar is).

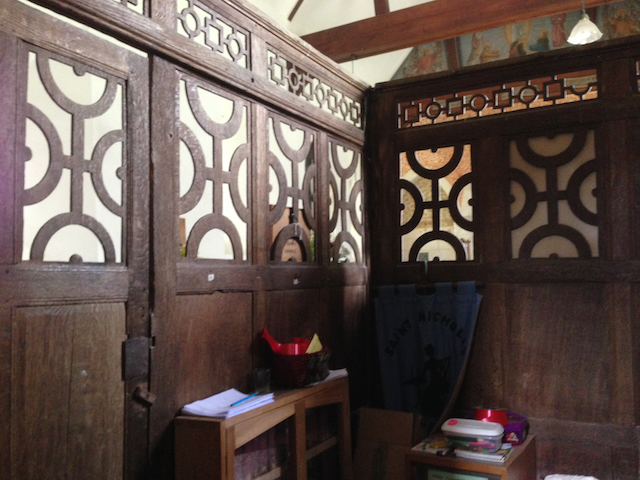

A large box pew, made of oak, was built in the seventeenth century for the lords of the manor. The Digweed family, who rented the manor house from the Knights, used this pew during Austen’s time. It was at the front of the nave, near the pulpit. The box pew is still in the church but has been moved to the back. It is now used as the vestry, the clergyman’s office.

So the Digweed family sat in state, protected from drafts and from curious eyes, at the front. Others, including the Austen family, likely sat on benches. If there weren’t enough benches, servants and the poor would have stood in the aisles and at the back. There was no gallery (balcony) in this church.

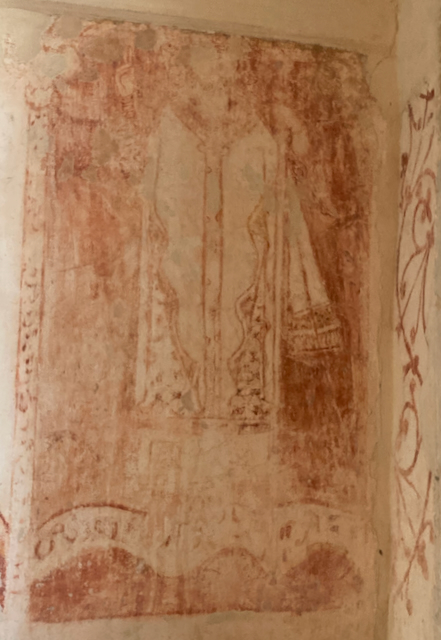

Some ancient wall paintings were found during one restoration of the church. These have been left uncovered. They were most likely covered by whitewash during Jane Austen’s time, however.

Other lovely decorations in the church are from Victorian times. The stained glass windows, pews, pulpit, baptismal font, choir stalls, and altar are all from the late 1800s, with the organ from the early 1900s.

Austen Documents

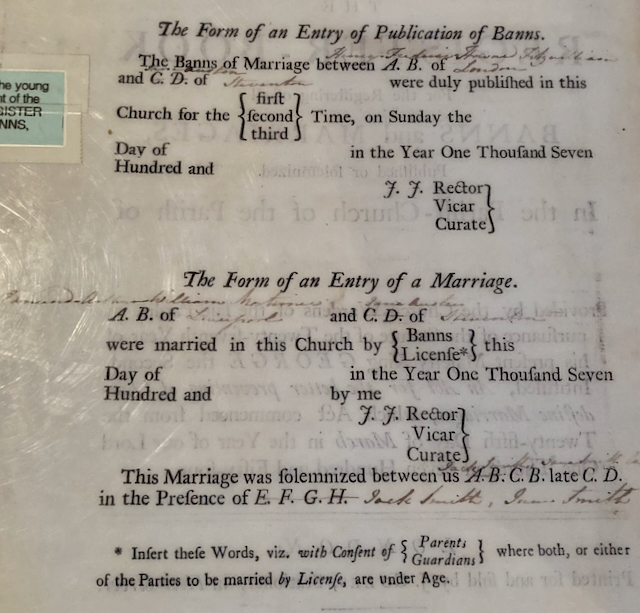

The church has reproductions of several church documents relating to Jane. (The originals are held at the Hampshire County Archives, which unfortunately I did not get a chance to visit.) The parish priest—in this case, Jane’s father, George Austen—kept the parish register for officially recording births, marriages, and deaths. The register included a sample page for marriages, and Jane playfully filled this out with imaginary names for her own future marriage.

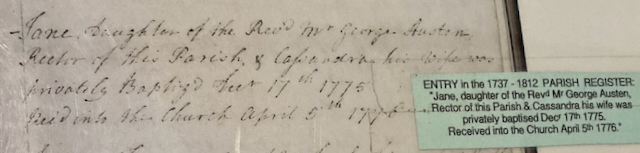

Another page of the parish register records Jane’s baptism at home on Dec. 17, 1775, shortly after her birth. She was born in the middle of a very cold winter, so her father christened her at home. She was officially received into the church on April 5, 1776, probably her first excursion.

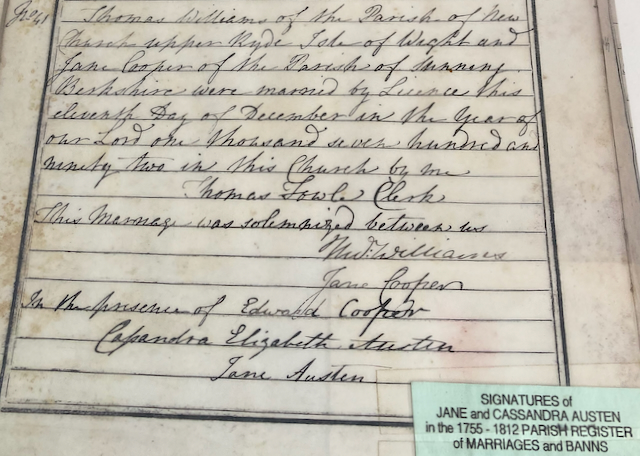

We can also see Jane and Cassandra’s signatures as witnesses to a wedding. Their first cousin Jane Cooper married Thomas Williams. Jane, Cassandra, and Edward Cooper (Jane Cooper’s brother and Jane Austen’s cousin), were the official witnesses.

Austen Memorials at Steventon Church

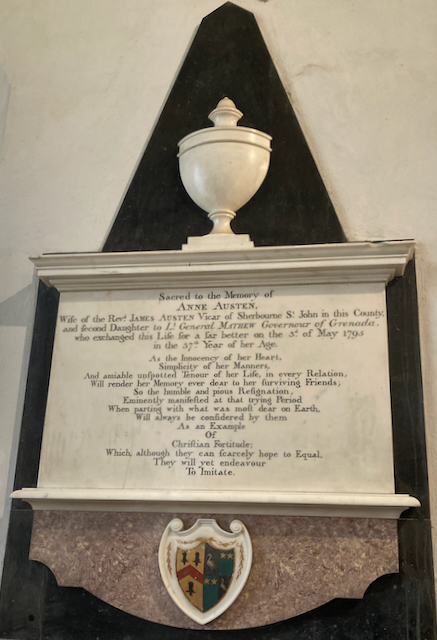

Inside the Steventon church, you can find memorial plaques to Jane’s brother James, James’s first wife Anne, and his second wife Mary. When Anne died in 1795, James was not yet rector of Steventon, so he is listed as vicar of Sherborne St. John.

When James died in 1819, the memorial says he “succeeded his father George Austen as rector of this parish.” George, of course, died in Bath and is buried at St. Swithin’s.

Mary’s memorial says that she died in 1843 at Speens, Berkshire, but was buried in Steventon (about 16 miles away) with her husband. Mary, of course, had left the rectory when her husband died and his brother Henry took over as rector.

James and Mary Austen’s grave is in the churchyard.

Knight and Digweed Memorials at Steventon

The Knight family owned the manor at Steventon from the early 1700s. They rented it to the Digweed family in 1758, and Digweeds lived there until 1877, though the Knights sold the property in 1855. (This was similar to Charles Bingley renting Netherfield and becoming the de facto squire of the parish.) Austen mentions some of the Digweeds in her letters.

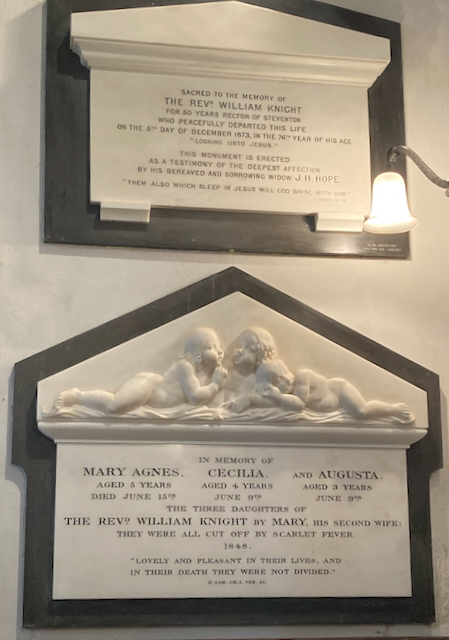

Memorials in the church commemorate Rev. William Knight, “50 years rector of Steventon.” He was Jane’s nephew who became rector after Henry. A sad memorial below his own records the deaths of William’s three daughters, ages 3, 4, and 5 years, who were all “cut off by scarlet fever” in one June week of 1848.

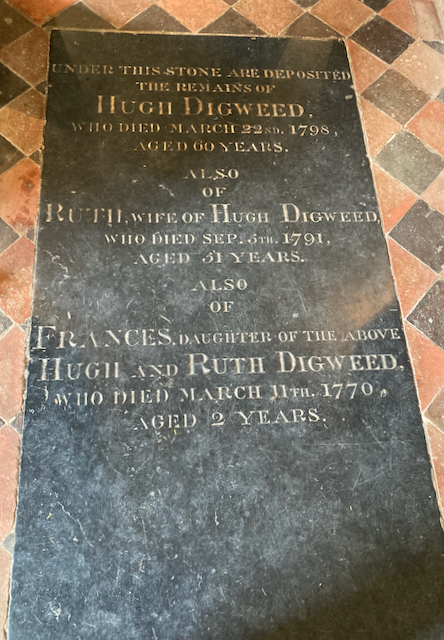

A ledgerstone on the church floor covers the grave of Hugh and Ruth Digweed, who died while Jane was at living at Steventon, and their daughter who died at age 2 in 1770. Other memorials enshrine later members of the Digweed family.

Some Digweeds, like these, are buried in the church, the most honored place to be buried, presumably since they were the squires of the manor house. Others are buried outside in the churchyard.

Steventon Church Today

Like most small country churches in England, Steventon is now part of a benefice including several churches, served jointly by a few clergy. Steventon belongs to the Overton Benefice, seven parishes all served by one rector, one vicar, and one curate.

The Steventon parish is still small, rural, and agricultural, as it was in Austen’s time. About 250 people live in the parish. Sunday services are still held at the church twice a month, usually with a dozen or so people in the congregation. One is a Communion service and the other may be matins, evensong, a holiday service, or a Saturday breakfast and talk for the wider community. Much larger crowds, up to 100 or even 200 people, come to events like holiday services, weddings, baptisms, and funerals. The church seats about 75-80 comfortably, so it can be quite crowded!

In Austen’s time, the church would get bitterly cold in the winter. A modern improvement is the addition of heaters under the pews. People in each pew can turn on their own heater, making the church much more comfortable without wasting energy by heating the whole church.

Marilyn Wright, the churchwarden, told me that she loves the peace of the church, and goes in there when she wants to pray and think. She said if her father, who has dementia, ever got lost, they would find him at the church. As I heard over and over in the Austen country churches, the church is still central to community life.

The Revd. Canon Michael Kenning, former rector of Steventon, gave our JASNA tour group a lovely introduction to the church. At the end, he pointed out that there are about 10,000 Church of England churches in the UK, and most do not get any funding from the National Trust, the British government, or the Church of England. Therefore they need outside funding. The Steventon church is currently in need of some major work. Damp has gotten into the walls, causing cracks and other damage. New drainage and other work is needed. After that, interior features of the church will be renovated.

If you wish to donate to the Steventon church, you can use this link.

JASNA provides support for such special projects at Austen family churches, including this one. If you are a JASNA member, donations to the churches fund for such projects are appreciated. (You can donate when renewing your membership, or sign in to your account and go under the drop-down menu to “Donate to JASNA or English Institutions.”)

For Further Exploration

During Austen time, Steventon had a Norman baptismal font. For an idea of what that might have looked like, as well as stories of St. Nicholas, see, The Winchester Type Fonts.

A Guide to St. Nicholas Church Steventon gives more details and pictures of all parts of the church and churchyard (follow links to further pages).

A Drive through Steventon to St Nicholas Church

A guide to the Steventon church, Jane Austen’s Steventon by Deirdre LeFaye, and guides to other Austen-related churches are available from Jane Austen Books.

Rectors and Vicars in Jane Austen

Posts on Other Austen Family Churches

Adlestrop and the Leigh Family

Great Bookham and Austen’s godfather, Rev. Samuel Cooke

Brenda S. Cox is the author of Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England. She also blogs at Faith, Science, Joy, and Jane Austen.