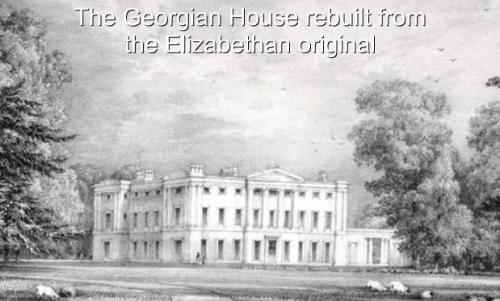

At Home With the Georgians: A Man’s Place, the BBC2 special, is hosted by Professor Amanda Vickery, who shares her expertise and unique knowledge gleaned from diaries written during that fascinating era. In the series about Georgian houses, shown in three installments in Great Britain, Dr. Vickery provides a fascinating insider’s view of what home and hearth meant to the individuals she showcases.

At Home With the Georgians: A Man’s Place, the BBC2 special, is hosted by Professor Amanda Vickery, who shares her expertise and unique knowledge gleaned from diaries written during that fascinating era. In the series about Georgian houses, shown in three installments in Great Britain, Dr. Vickery provides a fascinating insider’s view of what home and hearth meant to the individuals she showcases.

Host and scholar, Dr. Amanda Vickery in carriage

An 18th century gentleman, it seemed, yearned as much for domesticity as the Georgian woman. During this period the middle class began to earn enough money to purchase houses and furnish them in a style that reflected the owner’s tastes, character and moral values. Until a man could afford to head a household, his place in society as a full citizen was not fulfilled.

Dr. George Gibbs's letters to Miss Vickery

Take George Gibbs, a West Country doctor, for instance, who worked hard to woo his sweetheart, Miss Vickery. His future domicile and its furnishings were topics of much conversation in his letters to her. He looked for a house all over Exeter that would satisfy her as much as himself – “one with a good parlor with sashed windows and painted blue and with two chambers, tolerably good, and one hung with paper.”

Dudley Ryder fantasizes about a home and family in his humble one-room bachelor pad

Twenty-three year old Dudley Ryder, law student and son of a tradesman, yearned in his diaries for a wife to soothe his lonely nights and take care of him. He lived in squalid lodgings while studying law, eating his meals in chop houses and living a lonely bachelor existence.

In a contemporary cartoon, a bachelor cadges a meal from an irritated married friend

His dreams would not be realized for another twenty years when he married the daughter of a rich West Indian merchant.

Dudley Ryder as a respectable married man

Dudley not only came into his own later in life, but managed to acquire a quite handsome estate.

The Master Key to the Rich Ladies Treasures listed eligible ladies according to region and type

For these men, eligible brides were at a premium. A book, “Master Key to the Rich Ladies Treasures”, listed all the eligible women (and their incomes) in the land.

A lady's fortune and other assets could be consulted

Today, we think of the marriage mart in that long ago age as a “meat market” in which the bride went to the best prospect. Yet Georgian women longed as much for domesticity as the man yearned for a wife to complete his ambitions in becoming head of a household with a family.

John Courtney's house had curb appeal, unlike its master

Some men had more difficulty than others in acquiring a proper mate. John Courtney, who lived in a handsome house in the market town of Beverley in Yorkshire with his mama, was rejected eight times during his search for a wife. In this instance, Dr. Vickery makes the point that there was more to wooing a future wife than the prospect of living in a fine house – the man himself needed to have some finesse in the ritual of courtship and show some self-awareness.

The cost and maintenance of a carriage and horses was the equivalent of a helicopter today

Once the couple was married, the man could spend the family money as he wished. Much of a man’s financial outlay was on himself and his interests, such as horses, carriages, and leather (symbols of speed and virility) and on the sort of equipment that would be the equivalent of today’s laptops and flat screen tvs.

18th c. male items for sale today

Not surprisingly, the personalities of Georgian women varied. Not all were meek and mild. Miss Mary Martin from Essex was a rather complicated (and very bossy) individual. She was capable and demanding, yet womanly.

Miss Mary Martin oversees renovations

Engaged for seven years to her cousin, Colonel Isaac Rebow, she took care of his interests when he was away on garrison duty, jokingly writing to him, “I will only add that my breeches hang extremely well.” She was a powerful fiancee, able to oversee the hiring and firing of servants, look after storing Isaac’s wigs, and see after his provisioning. After they were married, she made sure that her husband was as happy in bed as out of it.

Charlotte Lucas was quietly content with her decision

At this juncture, Dr. Vickery points out that Charlotte Lucas in Pride and Prejudice, chose the security and status of a married woman, knowing she would be married to a buffoon. Through marriage she gained status and respectability. But what happened to a woman who never married? Unfortunately, as Jane Austen sagely wrote, “ There are not so many men of fortune in the world as there are pretty girls who deserve them.” In the 18th century, Dr. Vickery states, one out of three artistocratic girls were never married, for there were not enough estates to go around.

Even a buffoon of a husband did not detract from Charlotte's pride of home

And, indeed, Jane Austen in Mansfield Park wrote vividly about Fanny Price’s mother, who married down the social ladder. She took on her husband’s status, that of a lowly lieutenant, and lived a life of misery, poverty and want. Her tablecloths were surely dirty, whereas in the Georgian age a clean one was considered a sign of virtue.

Gertrude Savile, unhappy spinster

Dr. Vickery talks in detail of a lonely spinster, Gertrude Savile, who lives on sufferance in Rufford Abbey, her brother’s grand house in Nottinghamshire. Timid, shy, and pox marked, she hated her gilded caged life and struggled to find some social and emotional meaning in an existence that forced her to beg for “every pin and needle” and “every pair of gloves”. Even the servants treated her with contempt and thus she chose to remain within her rooms, with her cat her only comfort. In her diary she poured out her anger and sadness, using words like “miserable”, “unhappy”, “extremely miserable”, and “very unhappy”.

Gertrude Savile's agitated scribbles and crossings

Poor, poor Gertrude would never know the joys of managing her own household and overseeing her own brood. Her scribbled screams of rage and crossings leapt out from the pages of her journals.

George Hilton was full of self-loathing for his inability to control his base habits

Lifelong bachelors also felt the bitter pangs of loneliness. George Hilton, a dissolute 27-year-old squire, never married. He spent his time carousing in taverns, drinking to so much excess that he “fell paralytically drunk 220 times in eight years”. Even the men he drank with had no desire to introduce George to their eligible female relations. Graceless George had a house filled with pewter and devoid of womanly touches. His only female companions were prostitutes, which in a Christian society meant that he lived in sin. George died alone and was buried in an unmarked grave on the fells.

A serene view of Chawton Cottage

Romance and marriage for the Georgians was as complicated in a different way from courtship today. Women had fewer choices to make their way in the world, as poor Gertrude Savile situation as a spinster without prospects demonstrated, but many Georgian men yearned for domestic bliss as much as their women. Dr. Vickery ended the episode in Chawton Cottage, reminding us that another spinster, Jane Austen, chose to live a creative and productive life. Gertrude, who wallowed in her misery and anger, likely did not have the family support or innate talent that Jane had, and thus she was doomed to sit in her rooms alone.

Jane Austen's writing table, Chawton Cottage

I enjoyed this first installment by Dr. Vickery thoroughly. Her approach to what could have been a very dry topic was refreshingly unscholarly and accessible to even the most historically challenged (yet her script is backed up by impeccable sources.) While actors portrayed the diarists in various settings, we are shown the portraits of the actual individuals (when possible), and are shown their homes or a close facsimile.

Amanda Vickery reads Dudley Ryder's diaries

I did wonder, however, how on earth Dr. Vickery was allowed to handle valuable manuscripts with her bare hands. (Does not the oil on our fingertips eventually eat into the parchment? Are scholars exempt from having to wear gloves as they handle rare diaries that are stored in archival boxes?)

Portrait of Dr. George Gibbs

And I was a bit taken aback at her reaction to Dr. Gibbs’s portrait. Yes, he was a jowly man and did not resemble her fantasized movie star hero, but his lack of handsome looks in no way detracted (in my mind) from his tender feelings and consideration towards his wife and children. See this clip on YouTube. Still, this special made history come alive in a way that made me feel that I had met several people from a former time, and gave me a more complete understanding of their yearning for domestic bliss.

Next episode: A Woman's Touch, 9 Dec

BBC 2 will air the second installment, A Woman’s Touch, on Thursday evening at 9 PM. Viewers in countries round the world can only sit back and patiently wait for this excellent series to head their way.

More reading:

Read Full Post »