A few days after Jane [Austen’s] birth a blizzard struck and paralyzed all the south of England, making travel almost impossible as snow drifted deeply and blotted out all signs of roads and tracks. On four nights in January the temperatures sank so low that even urine in chamber pots underneath beds became frozen. It was weeks before a thaw occurred, and even then the spring was very cold, so Jane was not taken out to Steventon church for her christening until early April 1776. – Jane Austen: The World of Her Novels, Deirdre Le Faye

In Ways to Keep Warm in the Regency era, Part 1, the post ended with the invention of the Rumford fireplace, a vast improvement over previous fireplaces in which most of the heat from a fire went up the chimney and smoke billowed into the room. Not all people during the Regency period could afford the more efficient new fireplaces. There were ways, however, to capture heat and to prevent feeling ice cold on one side while too hot on the other.

Mid 18th century Wing Back Chair, England

Wing chairs

Arranged in a circle around a cozy fire, wing chairs served a dual purpose, conserving heat and protecting the sitter from draughts. English homes were notorious for chill draughts entering under doors and through ill fitting window frames. The highs backs of these chairs and wings, sometimes known as cheeks, prevented cold air from swirling around the head and upper body, and at the same time prevented heat from escaping past the sitter. High backed wood settees served a similar purpose but were not quite so comfortable.

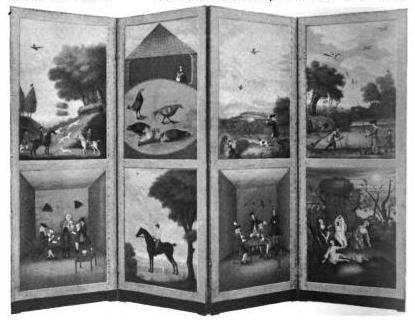

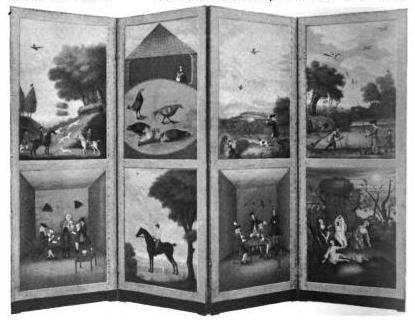

Room screens

Also known as draught screens, room screens have been used since medieval times as a protection against draughts. Thought of as a necessity, they partitioned off long halls and kept draughts from entering too close to the heated portion of the room. They could also serve as protection against too much sun in the summer in a room that faced west.

– Family Physician A Manual of Domestic Medicine, 1886

Draught Screen 1744

Of the tribe of fire screens and draught screens there are so many varieties that it is impossible to mention more than a tithe. The purpose of the former is so apparent as to need little commendation. So long as we are scorched baked or fried at one side of the room and frozen at the other so long shall we require at times a screen between the fire and those nearest it. This screen may take the form of transparent glass or tinted cathedral glass in leaded squares. It may have its panels of brocade, or old leather of rare needlework by skilful fingers, or of painting on panel in oils or in water colour. – The Furniture Gazette 1881

Pole screens

Pole screens

A beautiful addition to any room, decorative pole screens served an important function in the 18th century: The tall thin screens shielded people’s faces from the direct heat of the fire. In the 17th and 18th centuries both men and women wore makeup to hide blemishes. (It was said that before he turned fifty the Prince Regent’s face had turned waxen and copper colored from make up.) The cosmetic preparation worn to hide small pox was thick, and made up of wax and white lead. The lead was toxic, especially when warmed, and the heat from a fire could be life threatening. A pole screen protected the face from intense heat and prevented the wax from melting and the cosmetics from interacting with the skin. Pole screens were fitted with sliding panels that could be enlarged or diminished as needed. The earliest panels were made of wicker, but these were replaced with beautiful needlework or embroidered panels that came in many shapes and sizes – oval, heart-shaped, rectangular, etc. By the late 18th century, skin disfiguration caused by plagues was no longer as prevalent as before, and smaller polescreens became more fashionable.

The Bedroom

The bedroom remained a primary focus for staying warm. Privacy was a luxury only the rich or rising middle classes could afford. Most poor and working class families shared rooms (or lived in a one-room hovel), and children often shared a bed and huddled together. For the privileged, life was vastly different. A half hour before the family retired, a servant would enter the bedrooms and start a fire in each room. They would also warm the bed sheets with bed warmers.

Bed warmers

Brass bed warmer open

Bed warmers like the one depicted in the image above were made of brass tin or lined copper, and had long wood handles. The round metal pan was hinged so that it could be easily filled with hot coals. The pan would then be moved gently back and forth between the sheets to warm the beds on cold evenings. These bed warmers gradually fell into disuse in the 19th century after hot water bottles made of rubber became affordable and widespread.

Four poster beds

The thick hangings that surrounded a four poster or tester bed kept cold draughts out and body heat in. Popular since before the Elizabethan age, their design changed with the times: ornate in the 16th century, plain in the 18th century, and a rich but restrained neoclassical style in the 19th century. The bed and bedding materials varied according to wealth. Luxurious hanging made of velvet or brocade were often worth more than the wood bed frame, and in times past the rich would take the hangings with them as they traveled, leaving the wood bed behind. As improvements in insulation and draught exclusion were made, the four poster bed became more decorative than functional.

Four poster bed

Night caps (also known as jelly-bags in the 19th century).

Knitted wool or silk stocking caps provided warmth while sleeping. This distinctive cap was also used other than for sleeping. From the 14th-19th century it was known as a skullcap and worn indoors by men when they removed their wigs. Women wore a more ornate mob cap during the day, to bed, and outdoors under their hats.

Nightcaps are no protection against snoring

Foot warmers

Foot warmers were small, practical and transportable. Most foot warmers were simple wood, tin, or brass boxes with metal trays that held hot coals. The sides were poked with holes in a patterned design, and a rope or metal handle allowed for easy portability. Women and children would carry footwarmers to church or inside a carriage. They were used in a cold room as well. Women’s long skirts would hang over the warmer, providentially holding the heat around their feet. By the end of the 19th century, footwarmers were primarily used in sleighs and carriages until the advent of the automobile

Foot warmers were small, practical and transportable. Most foot warmers were simple wood, tin, or brass boxes with metal trays that held hot coals. The sides were poked with holes in a patterned design, and a rope or metal handle allowed for easy portability. Women and children would carry footwarmers to church or inside a carriage. They were used in a cold room as well. Women’s long skirts would hang over the warmer, providentially holding the heat around their feet. By the end of the 19th century, footwarmers were primarily used in sleighs and carriages until the advent of the automobile

High-sided Church Pews:

For about 54 shillings a year a family could rent a high sided pew whose tall wooden walls protected worshipers from winter drafts. Family members would sit close together and share the heat from a foot warmer. The pews were often individualized by family members who brought in their own pillows or fabrics, and even furniture. Pews in the galleries were for parishioners who could not afford to rent a box downstairs.

Family Pew, Tichborne

Read more about this topic at these links:

First Image, Rossetti’s Bed

Read Full Post »

Historic fruit trees were discovered in a National Trust garden in Ickworth House estate, Suffolk.

Historic fruit trees were discovered in a National Trust garden in Ickworth House estate, Suffolk.

Pole screens

Pole screens

Foot warmers were small, practical and transportable. Most foot warmers were simple wood, tin, or brass boxes with metal trays that held hot coals. The sides were poked with holes in a patterned design, and a rope or metal handle allowed for easy portability. Women and children would carry footwarmers to church or inside a carriage. They were used in a cold room as well. Women’s long skirts would hang over the warmer, providentially holding the heat around their feet. By the end of the 19th century, footwarmers were primarily used in sleighs and carriages until the advent of the automobile

Foot warmers were small, practical and transportable. Most foot warmers were simple wood, tin, or brass boxes with metal trays that held hot coals. The sides were poked with holes in a patterned design, and a rope or metal handle allowed for easy portability. Women and children would carry footwarmers to church or inside a carriage. They were used in a cold room as well. Women’s long skirts would hang over the warmer, providentially holding the heat around their feet. By the end of the 19th century, footwarmers were primarily used in sleighs and carriages until the advent of the automobile