Copyright (c) Jane Austen’s World. Post written by Tony Grant, London Calling.

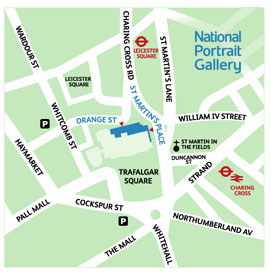

The pencil and watercolour picture Cassandra made of Jane Austen in about 1810, is in the National Portrait Gallery, St Martin’s Place, London, just off Trafalgar Square. It is unique within the exhibits there because, although it is grouped with other 18th century portraits, it is displayed in a glass case on a plinth in the general concourse of room 18. It is not hung on the walls with her other contemporaries.

Jane Austen by Cassandra Austen, pencil and watercolour, circa 1810

The portrait is also unique in another way. It is the only portrait within the gallery made by an amateur. All the other portraits are of famous politicians, the lords and ladies of the time, rich merchants and industrialists, and the powerful. They were painted for a particular purpose by professional artists, some of whom, like Sir Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough and Thomas Lawrence, were the best, most sort after and amongst the most brilliant artists of their day. Cassandra, was an ordinary, lower middle class person dabbling in sketching and painting for her own interest and edification. A pastime, thousands of other ladies participated in, along with playing the pianoforte, singing and dancing. It was an important element in their home entertainment. We can only guess as to why Cassandra drew a portrait of Jane on that day in 1810 and for what purpose. The drawing and painting process, techniques and style of famous artists like Reynolds , Gainsborough and Lawrence can be found out through evidence and documents, expert analysis of their paintings and by charting their careers as painters. How Cassandra sketched can only be surmised. But one thing is for sure, you can look at her sketch of Jane carefully and there are no apparent errors or mistakes. There is no working out on the picture. It is a finished product. So how did Cassandra produce it and what does it tell you and I about Jane and Cassandra?

From where I live it is an interesting journey to The National Portrait Gallery. I go out of my front door, turn right and walk for five hundred yards, past the newsagents, butchers, chemist and green grocers in Motspur Park, to the station. Motspur Park being part of the London Borough of Merton and next to the town of Wimbledon. It’s famous for the London University playing fields and athletics track and it is home to Fulham Football Club’s training ground. The one-minute mile was nearly broken at the London University track here in the 1950’s.before it was eventually achieved at Oxford.

The train journey from Motspur Park, passing through, Raynes Park, Wimbledon, Earlsfield, Clapham Junction, Vauxhall and Waterloo takes about twenty minutes. It is sixteen miles to the centre of London from where I live.

Waterloo Station. Image @Wikimedia Commons

Waterloo Station is an Edwardian masterpiece of acres of glass roof corrugated like a sea of glass waves. Beneath its roof, during the April of 1912, the rich and wealthy caught the boat train to Southampton Docks and then bordered The Titanic. Millions of soldiers between 1914 and 1918 caught troop trains to the same Southampton Docks to board troop ships for France and the trenches. In the Second World War, the same again. Millions of troops travelled from Waterloo to Southampton to sail to Normandy. In Waterloo the ghosts of the past begin to cling to your consciousness like suffocating cobwebs. The giant concourse clock hanging from the roof reminds you of the lovers trysts famously enacted beneath it’s ticking mechanism from the time the station began.

Villiers Street. Image @Wikimedia Commons

Walking out of Waterloo station on to the South bank and the breezes of The River Thames brings it’s ghosts too, of millennia’s of people, famous, infamous, notorious and where many events throughout history took place. You walk across the pedestrian path attached to Hungerford Railway Bridge across which Virginia Woolf walked and along Villiers Street next to Charring Cross Station and past where Rudyard Kipling lived when he came back from India, past the house where Herman Melville lived for a short while and past the house where Benjamin Franklin lived for many years with his common law wife and wrote, printed, invented and had revolutionary ideas.

![twinings[1]](https://janeaustensworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/twinings1.jpg?w=249&h=300)

Twinings. Image @Tony Grant

You go past where Charles Dickens had his office for Household Words, past the recumbent statue to Oscar Wilde, “I may be in the gutter but I’m looking at the stars.,” past Twinings, where Jane Austen bought her tea, past the present day protest outside Zimbabwe House to the atrocities that are happening, as I write, in that country, past St Martins in the Fields,…

Trafalgar Square. Image @Wikimedia Commons

… then into Trafalgar Square, Nelsons Column, Landseers giant lions and round the side of The National Gallery and into the entrance of The National Portait gallery in St Martin’s Place, opposite The Garrick Theatre. All those ghosts now thickly clinging about neck, arms, legs and hair, streaming like veils of gossamer as you walk, playing with the imagination.

Entrance to the National Portrait Gallery. Image @Tony Grant

The entrance to The National Portrait Gallery is inauspicious. It is arched and fine but doesn’t compare with the more grandiose entrance in Trafalgar Square of The National Gallery with it’s entrance on a raised platform, Ionic pillars, fine Greek portico and temple dome. Entering, The Portrait Gallery, is almost like going into the sombre muted entrance of a cathedral. Some arches, mosaic floor, heavy wooden doors to right and left and then up some limestone steps.

Escalator up to the second floor

Once at the top of the entrance staircase you enter into a modern, light and airy hall with a ceiling four floors high and a tall escalator reaching high, up to the second floor.

Looking down.

Open plan galleries , rows of computer screens and a library for research are to your right as you go up the escalator.

On the way to the second floor. Image @TonyGrant

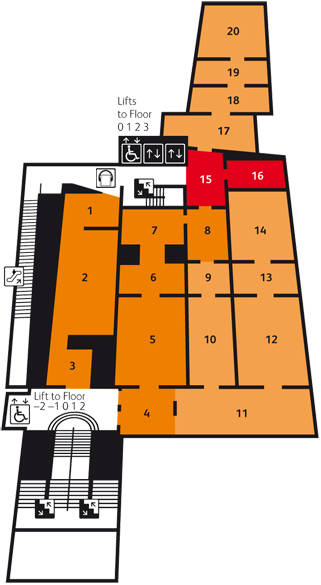

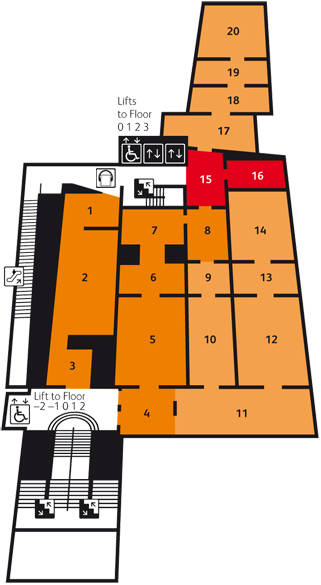

Cassandras portrait of Jane is on the second floor in room 18. As you get to the top of the escalator turn left and you are soon in room 18.

Second floor of the National Portrait Gallery, Room 18

The walls have the rich and famous of the early 19th century hanging on them but just to left and almost as soon as you enter the gallery, there is a glass cube positioned on a plinth and the painting in it is about chest height. It is Cassandra’s portrait of Jane, set within a heavy, elaborate, gold frame.

Jane Austen's portrait framed and in situ.

The frame seems too heavy and wide for the small picture. It dominates the picture. The portrait is positioned so the back of it is towards you. You have to walk around it to see it.

Mezzotint print of Gainsborough's portrait of the Duchess of Devonshire

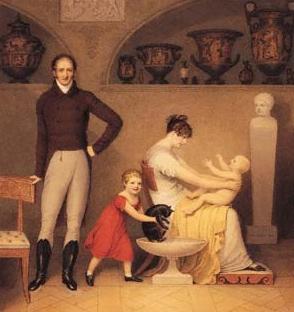

We can compare a portrait executed by Thomas Gainsborough, with Cassandra’s sketch of Jane. The portrait of Georgianna The Duchess of Devonshire done by Gainsborough in 1787, is nicknamed, “the large black hat,”and has many similarities to Cassandra’s portrait of Jane. Both show the sitter with their face in profile, Jane facing left and Georgianna facing right. Both have curled and ringletted hair, both have young smooth looking faces and both have their arms folded in front of them. Gainsborough’s portrait of Georgiana is about fashion, position in society, and has a beautiful and intelligent face. The way she is standing, side on, even with the luxurious folds , creases and layers of the expensive materials of the dress and bodice you can see the sensuous curve of her back, the relaxed slender manicured fingers of her left hand are resting on her right arm. Georgianna’s eyes are looking straight at the observer, inviting you to look back and admire, a slight whimsical glance and that mouth, sensuous, waiting to be kissed. The picture speaks of wealth, confidence, beauty, calmness, style, luxury and is executed by a master painter at the top of his profession.

Jane Austen by Cassandra Austen. Image @National Portrait Gallery

Cassandras picture on the other hand shows Jane, shoulders full on towards the observer. She looks solid and lumpy. The drawing is a pencil sketch. The four fingers of the left hand resting on her right arm is a claw, four talons, more appropriate on a hawk. What disappoints me most is that Jane is looking away. If Cassandra had got her to look at her and had drawn a direct look, I would have forgiven all the amateurism and lack of skill shown in the picture. That one thing would have had Jane Austen looking at us. We could have made contact, seen into her soul. That would have lifted the picture immeasurably. Georgiana looks at us and we immediately have a relationship with her. Cassandra keeps Jane away from us. She keeps her private. Maybe that one fact tells us about Jane and Cassandra’s relationship. Or, perhaps Cassandra was trying, merely, to keep to the conventions of portraiture too closely. It showed lack of imagination. The mouth is thin, small and tight. Not one to be kissed easily. There is some colour in her cheeks. Her face is given a three-dimensional quality by the deep, long, unattractive creases leading from the wings of her nostrils to the corners of her mouth. There is a long aquiline nose, smooth and thin. Her eyebrows are pronounced, dark thin curves above her wide-open intelligent eyes. In some way the eyes do save the picture even though you do not have eye contact. They show wide-open, hazel orbs, thoughtful and carefully looking. The pronounced fringe of curls and ringlets above her brow are what strike you most about the picture. Cassandra wanted to emphasise them for some reason. Maybe she could draw hair better than other things.

One other thing. This picture was made in 1810. Jane was thirty-five years old. The picture is of a girl no older than a teenager.

When sketching, a sketcher has to look and look and keep looking. They make many marks, some right and some wrong. A process of catching the subject happens on the paper. There is no sign of a sketching process going on in this picture. Either Cassandra drew without wanting to change anything so keeping mistakes, although I think that is impossible for an artist, or she did a series sketches first and then created this one from her rough attempts. I think she did make other sketches leading up to this finished product. Presumably, like many of Jane’s letters they were destroyed by Cassandra in later life.

Queen Elizabeth I, one of Jane Austen's neighbors.

This poor, amateurish and unsatisfying drawing of Jane Austen is in pride of place in room 18 of The National Portrait Gallery. There it is, amongst some of the finest examples of 18th and early 19th century portraits. It is one of the most popular pictures in the gallery. It is Jane Austen.

Gentle reader: This post was written by Tony Grant from London Calling. Except for the Wikimedia images, he provided all the images for this post.

More on the topic:

Read Full Post »

![twinings[1]](https://janeaustensworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/twinings1.jpg?w=249&h=300)