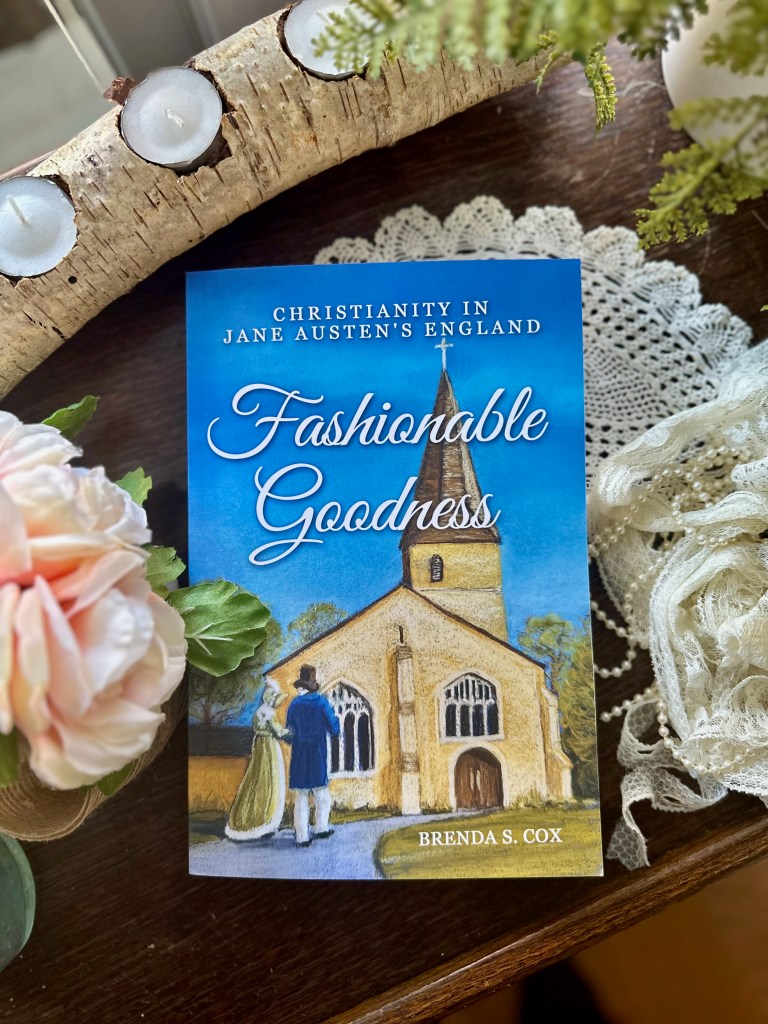

Our very own Brenda S. Cox has just published her new book Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England. It’s already receiving a wonderful reception, and I know it will continue. For those of us who are always expanding our understanding of Jane Austen’s life, and particularly her personal life and faith, this new book is an essential resource.

When I was writing my book Praying with Jane: 31 Days Through the Prayers of Jane Austen, I read every article and book I could find on the topic of religion and faith as it related to Austen and her family. I scoured every available resource on Austen’s personal faith, her family’s daily and weekly religious habits, and the Anglican church at large. I discovered many wonderful details about her religious life, but as I worked, I always felt as though I was putting together a giant puzzle. And when it came to understanding more fully the implications of her religious beliefs and background in her novels, I felt as though the puzzle was missing many important pieces.

In Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England, Brenda has finally put the puzzle pieces in their rightful places and collected all of the information one might want to know about Jane Austen’s religious life in one handy place. This book covers a broad range of topics that any Jane Austen lover can benefit from knowing, especially for those of us who enjoy looking into the varied layers and greater context of her writing.

Of particular interest is the clever manner in which Brenda has organized the information in this book. Each chapter is easy to find, plus she has included many helpful resources at the end of the book, including handy tables with income information, terminology, ranks within the church, and denominations; several appendices; detailed chapter notes; a hefty bibliography; a glossary of terms; and a topical index. You can read this book cover-to-cover or you can pick and choose the topics that interest you most.

I highly recommend this book for any Austen fan or scholar. Without this book, you can only know part of what makes Jane Austen’s characters and plots so intriguing. Thank you Brenda for creating this invaluable resource!

(See below for giveaway details.)

About the Book:

“Brenda Cox’s Fashionable Goodness is an indispensable guide to all things religious in Jane Austen’s world. . . . a proper understanding of 18th century Christianity is necessary for a full appreciation of Austen’s works. Cox provides this understanding. . . . This work will appeal to novice readers of Austen as well as scholars and specialists.”

Roger E. Moore, Vanderbilt University, Jane Austen and the Reformation

The Church of England was at the heart of Jane Austen’s world of elegance and upheaval. Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England explores the church’s role in her life and novels, the challenges that church faced, and how it changed the world. In one volume, this book brings together resources from many sources to show the church at a pivotal time in history, when English Christians were freeing enslaved people, empowering the poor and oppressed, and challenging society’s moral values and immoral behavior.

Readers will meet Anglicans, Dissenters, Evangelicals, women leaders, poets, social reformers, hymn writers, country parsons, authors, and more. Lovers of Jane Austen or of church history and the long eighteenth century will enjoy discovering all this and much more:

- Why could Mr. Collins, a rector, afford to marry a poor woman, while Mr. Elton, a vicar, and Charles Hayter, a curate, could not?

- Why did Mansfield Park‘s early readers (unlike most today) love Fanny Price?

- What part did people of color, like Miss Lambe of Sanditon, play in English society?

- Why did Elizabeth Bennet compliment her kind sister Jane on her “candour”?

- What shirked religious duties caused Anne Elliot to question the integrity of her cousin William Elliot?

- Which Austen characters exhibited “true honor,” “false honor,” or “no honor”?

- How did William Wilberforce, Hannah More, and William Cowper (beloved poet of Marianne Dashwood and Jane Austen) bring “goodness” into fashion?

- How did the French Revolution challenge England’s complacency and draw the upper classes back to church?

- How did Christians campaigning to abolish the slave trade pioneer modern methods of working for social causes?

About the Author, Brenda S. Cox:

Brenda S. Cox has loved Jane Austen since she came across a copy of Emma as a young adult; she went out and bought a whole set of the novels as soon as she finished it! She has spent years researching the church in Austen’s England, visiting English churches and reading hundreds of books and articles, including many written by Austen’s contemporaries. She speaks at Jane Austen Society of North America meetings (including three AGMs) and writes for Persuasions On-Line (JASNA journal) and the websites Jane Austen’s World and her own Faith, Science, Joy, and Jane Austen.

Buy the Book:

You can purchase Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England here:

Amazon and Jane Austen Books

International: Amazon

Book Giveaway:

To enter for a chance to win a copy of Brenda’s book Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England, please leave a comment below with an answer to this question:

What is one question you’ve always had about Jane Austen’s faith or the role religion plays in her novels?

Giveaway Details: This giveaway is for ONE (1) print copy and ONE (1) ebook (Kindle) edition for readers of this blog. The winners will be drawn by random number generator on November 18, 2022.

Note: This giveaway is limited to addresses in the U.S., U.K., Australia, Canada, Germany, Spain, France, or Italy for a print copy of the book. The author can only send a giveaway ebook (Kindle) to a U.S. address. (However, both the ebook and paperback are available for sale to customers from any of these countries, and some others that have Amazon.)

Blog Tour Schedule

- Oct. 20 Jane Austen’s World, Vic Sanborn, Interview

- Oct. 21 My Jane Austen Book Club, Maria Grazia, Book Giveaway and Guest Post, “Sydney Smith, Anglican Clergyman and Proponent of Catholic Rights, Potential Model for Henry Tilney”

- Oct. 22 Clutching My Pearls, Lona Manning, Book Review

- Oct. 23 Jane Austen Daily on Facebook, Austen and Her Nephews Worship (1808)

- Oct. 25 Fashionable Goodness Book Excerpt and Giveaway, Jane Austen in Vermont, Deborah Barnum, Book Giveaway, Review, Excerpt from Chapter 1, and Interview

- Oct. 25 “Jane Austen and Fashionable Goodness,” History, Real Life and Faith, Michelle Ule, Book Review

- Oct. 27 Australasian Christian Writers, Donna Fletcher Crow, Guest Post, “Seven Things Historical Fiction Writers Should Know about the Church of England”

- Oct. 30 Regency History, Andrew Knowles, Book Review and Video Interview with the author

- Nov. 1 So Little Time, So Much to Read!, Candy Morton, Guest Post, “Women as Religious Leaders in Austen’s England”

- Nov. 2 Fashionable Goodness and Jane Austen’s Use of Faith Words, Austen Variations, Shannon Winslow, Interview and Review

- Nov. 3 Laura’s Reviews, Laura Gerold, Book Review

- Nov. 4 Jane Austen’s World, Rachel Dodge, Book Review and Book Giveaway

- Nov. 5 Kindred Spirit, Saved by Grace, Rachel Dodge, Book Review

- Nov. 7 The Authorized Version, Donna Fletcher Crow, Book Review and Excerpt

- Nov. 8 Inspired by Life and Fiction, Julie Klassen, Book Review and Guest Post, “Jane Austen at Church”

- Jan. 10 The Calico Critic, Laura Hartness, Book Review

RACHEL DODGE teaches college English classes, gives talks at libraries, teas, and book clubs, and writes for Jane Austen’s World blog. She is the bestselling author of The Little Women Devotional, The Anne of Green Gables Devotional and Praying with Jane: 31 Days Through the Prayers of Jane Austen. Coming soon: The Secret Garden Devotional! You can visit Rachel online at www.RachelDodge.com.