By Brenda S. Cox

“Edward & I settled that you went to St. Paul’s Covent Garden, on Sunday.”—Jane Austen, letter to Cassandra from Godmersham Park, Oct. 26, 1813

Covent Garden

We’ve been visiting London churches mentioned in Austen’s novels. Now let’s go to one mentioned in her letters. In the fall of 1813, Jane was staying with her brother Edward and his family at Godmersham Park. Cassandra was visiting their brother Henry at 10 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, London. He lived in a flat above his bank. (For locations Henry lived in London, see Jane Austen’s Visits to London.) Covent Garden was known for its fruit and vegetable market, as well as, unfortunately, its prostitutes.

Jane Austen’s London offered two official theatres, at Drury Lane and Covent Garden. Both were in the church parish served by St. Paul’s Covent Garden, and Austen saw plays at both. She was planning to see a play at the Covent Garden theatre when she visited Henry a month earlier:

“Fanny and the two little girls are gone to take places for to-night at Covent Garden; “Clandestine Marriage” and “Midas.” The latter will be a fine show for L. and M.” (Lizzie and Marianne)—Sept. 15, 1813 (Fanny was the eldest daughter of Jane’s brother Edward Austen Knight; her mother had died five years earlier. Lizzie and Marianne were Fanny’s younger sisters. Edward was with them but staying at a nearby hotel.)

Jane and Edward assumed Cassandra would go to church at St. Paul’s Covent Garden, since it was Henry’s parish church. Jane probably attended that church herself when any of her visits to Henrietta Street lasted over a Sunday. She and her family regularly attended church on Sundays, wherever they were.

The Actors’ Church

The Covent Garden area today offers more than twenty theatres. St. Paul’s, called “The Actors’ Church,” hosts concerts and plays in the church and in its walled garden. They have an in-house professional theatre company, Iris Theatre. The church’s summer schedule for this year includes Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice, along with several Shakespeare productions and children’s shows. To accommodate such events, the church replaced deteriorating Victorian pews with custom-made movable and stackable pews.

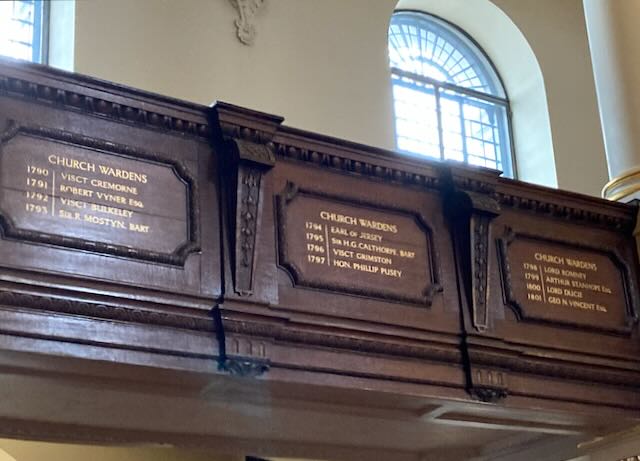

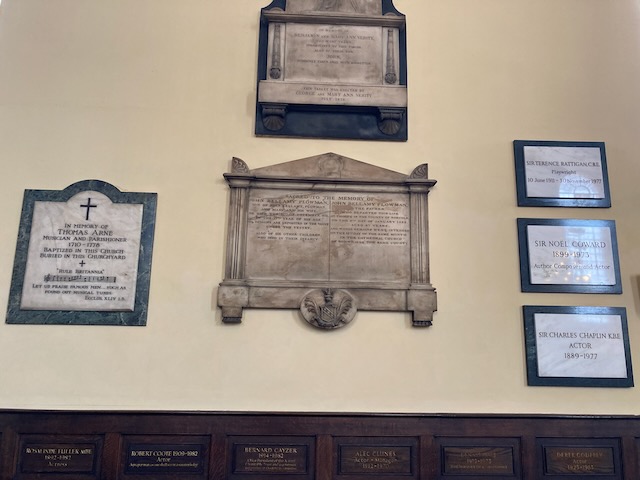

The inside of the church commemorates famous entertainers wherever you look. Hundreds of plaques adorn the walls of the church, the backs of the pews, and the garden benches and walls.

Some plaques are memorials to the church’s leaders and parishioners, as you would see in other English churches. But most remind visitors of famous people such as Vivien Leigh (star of Gone with the Wind), Boris Karloff (who played Frankenstein’s monster), Thomas Arne (who wrote “Rule, Britannia” around 1740), Sir Charles Chaplin (Charlie Chaplin), and others.

Besides actors and actresses, plaques commemorate dancers, singers, directors, theatre managers, patrons, choreographers, drama teachers, playwrights, and even a “critic, journalist, wit.” One woman is listed as “Actress, Producer, Supernova.” The church charges hefty fees to install these plaques (around £3000 for a plaque on the wall). These fees have kept the church solvent.

History

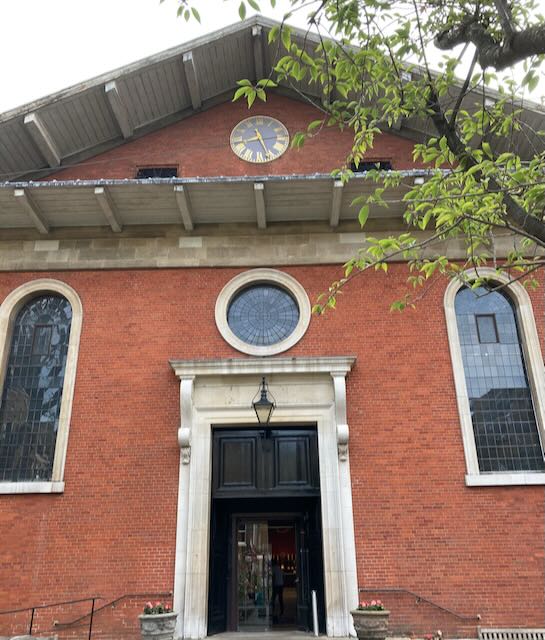

The church was designed by Inigo Jones and consecrated to St. Paul in 1638.

Jones designed it with a great East Door into the main piazza of Covent Garden. However, that would have put the altar at the west end of the church, which went against Christian tradition. At the last moment, the Bishop of London decreed that the altar had to be in the east end of the church, so the East Door doesn’t open. Entry is through the churchyard, from the sides of the building.

Various famous people are buried in the churchyard, including the painter JMW Turner and the first victim of the Great Plague of London, who died in 1665. In the 1850s, Parliament stopped all burials in central London churches. At that time, the headstones were removed and the gardens laid out as they are today.

A fire destroyed much of the church in 1795, but it was rebuilt so that today it is much as Austen would have seen it.

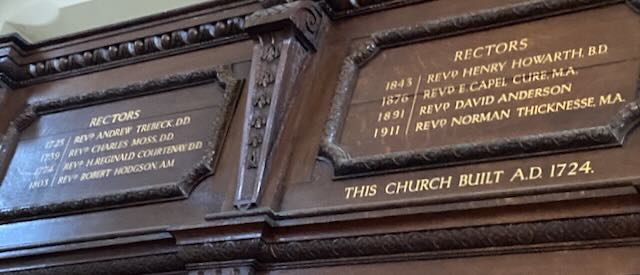

Rectors

When Jane Austen was there, Edward Embry was the rector, from 1810-1817. She might have heard him preach, but she does not mention him in her letters. His portrait is in the National Gallery.

The rector who kindly showed us around when we visited was Rev. Simon Grigg, who has been rector since 2006. His bio says “When not in church you will usually find him in a bar, a theatre or the gym.” The assistant rector, Rev. Richard Syms, is a professional actor and theatre manager as well as a priest.

Worship

The church offers communion services on Sundays and Wednesdays, and brief Morning Prayer services Tuesday through Friday. Their choir sings Choral Evensong once a month. Rev. Grigg told us that attendance on Sundays is about 50 people, plus those who attend online. The church seats 200.

They have larger services for Easter and for midnight mass on Christmas Eve. Of course they also host weddings, baptisms, and funerals. According to their website, “St Paul’s is well known because of its memorial services for members of the theatrical and entertainment community, but we also offer them for the local community.”

Inclusion

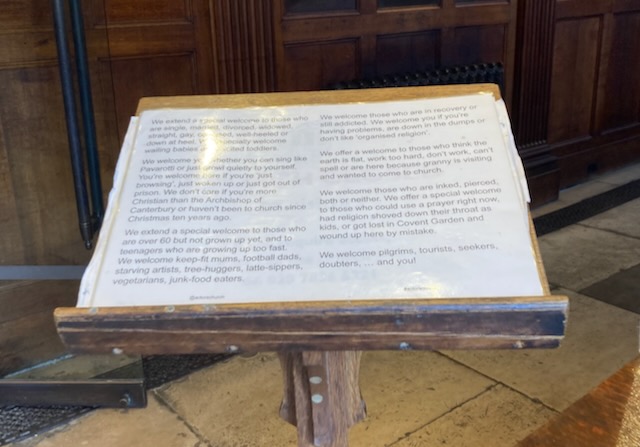

The church seeks to be inclusive, according to their website and this entry sign:

“We extend a special welcome to those who are single, married, divorced, widowed, straight, gay, confused, well-heeled or down at heel. We especially welcome wailing babies and excited toddlers.

We welcome you whether you can sing like Pavarotti or just growl quietly to yourself. You’re welcome here if you’re ‘just browsing’, just woken up or just got out of prison. We don’t care if you’re more Christian than the Archbishop of Canterbury or haven’t been to church since Christmas ten years ago.

We extend a special welcome to those who are over 60 but not grown up yet, and to teenagers who are growing up too fast. We welcome keep-fit mums, football dads, starving artists, tree-huggers, latte-sippers, vegetarians, junk-food eaters.

We welcome those who are in recovery or still addicted. We welcome you if you are having problems, are down in the dumps, or don’t like ‘organized religion’.

We offer a welcome to those who think the earth is flat, work too hard, don’t work, can’t spell or are here because granny is visiting and wanted to come to church.

We welcome those who are inked, pierced, both or neither. We offer a special welcome to those who could use a prayer right now, had religion shoved down their throats as kids, or got lost in Covent Garden and wound up here by mistake.

We welcome pilgrims, tourists, seekers, doubters, . . . and you!”

No doubt Jane Austen and her family would have felt welcome in the church, especially with their love of the theatre.

All photos in this post ©Brenda S. Cox, 2025

More Information about St. Paul’s Covent Garden

Self-Guided Tour, explaining parts of the church and giving prayers

Visitor Information and schedule of events

Churches Mentioned by Name in Jane Austen’s Novels

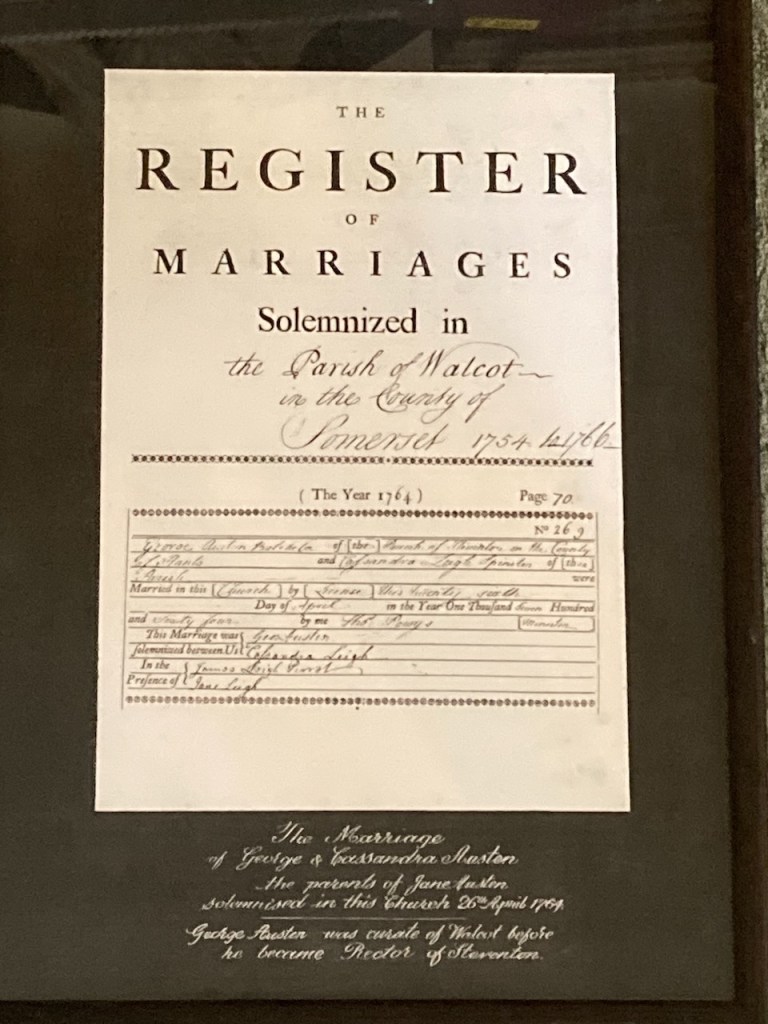

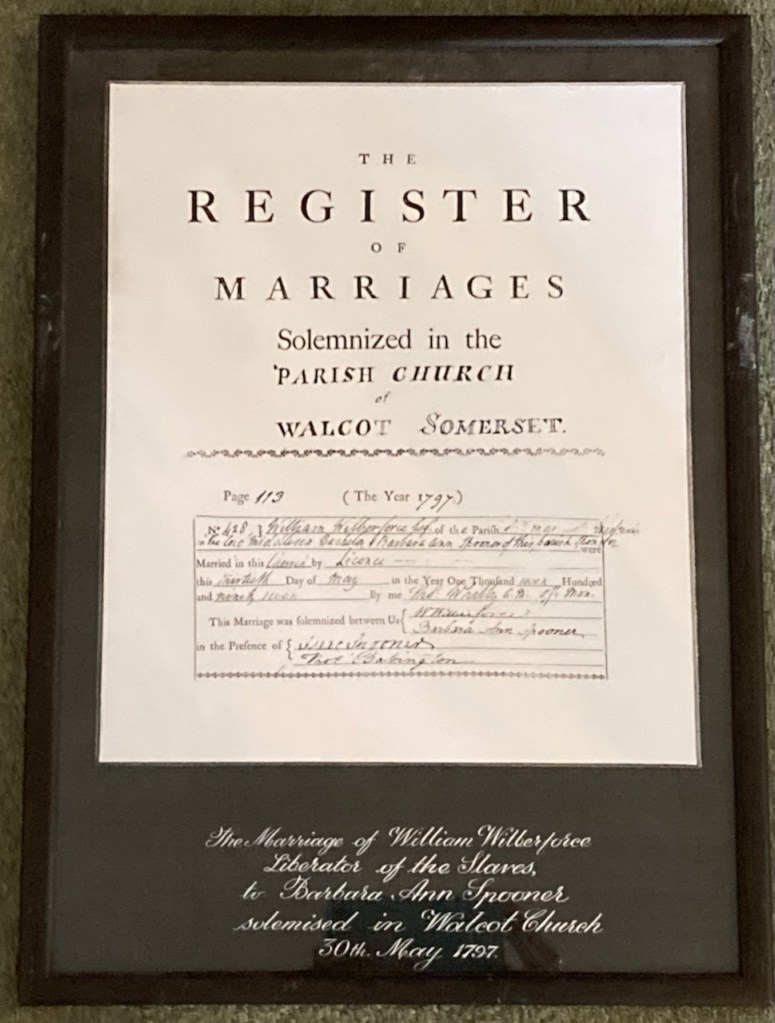

St. Swithin’s, Walcot and other churches in Northanger Abbey

London Churches in Austen’s Novels

Austen Family Churches

Hamstall Ridware and Austen’s First Cousin, Edward Cooper

Adlestrop and the Leigh Family

Stoneleigh Abbey Chapel and Mansfield Park

Great Bookham and Austen’s Godfather, Rev. Samuel Cooke

Brenda S. Cox is the author of Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England. She also blogs at Faith, Science, Joy, and Jane Austen.