As spring turns to summer on our month-by-month exploration of Jane Austen’s life, letters, and novels, we turn our attention to June in Jane Austen’s world. If you’re new to the series, you can find previous articles in this “A Year in Jane Austen’s World” series here: January, February, March, April, and May.

Last month, we enjoyed the beauty of springtime coming to Chawton, along with the beautiful blooms of May. Let’s take a look at our monthly view of Chawton House Gardens. Many visitors will come tour the gardens over the next few months to enjoy the garden walks, see the house, and perhaps stay for tea.

June in Hampshire

June is the time of year when England turns into a beautiful garden of scenic greenery, lush fields, and lovely flowers. Hampshire is one of the prettiest places you can visit. I’ve been to Hampshire in the spring and early summer several times, and I highly recommend a summer trip if the opportunity ever presents itself. It’s also time for berries!

“Yesterday I had the agreable (sic) surprise of finding several scarlet strawberries quite ripe;- had you been at home, this would have been a pleasure lost. There are more Gooseberries & fewer Currants than I thought at first.- We must buy currants for our Wine.-” (Jane Austen writing to Cassandra from Chawton Cottage in June 1811)

Here is Jane Austen’s House Museum and the roses that frame the front door this time of year:

June in Jane Austen’s Letters

We have several letters from June to explore. After the “season” ended, many rich families left London and went to the countryside or Bath. Jane and her family frequently traveled to visit family members or friends for longer visits during the summer months.

2 June 1799 (Queen’s Square, Bath):

- Edward’s health: “What must I tell you of Edward? Truth or falsehood? I will try the former, and you may choose for yourself another time. He was better yesterday than he had been for two or three days before,—about as well as while he was at Steventon. He drinks at the Hetling Pump, is to bathe to-morrow, and try electricity on Tuesday. He proposed the latter himself to Dr. Fellowes, who made no objection to it, but I fancy we are all unanimous in expecting no advantage from it. At present I have no great notion of our staying here beyond the month.”

- Visits with friends: “I spent Friday evening with the Mapletons, and was obliged to submit to being pleased in spite of my inclination. We took a very charming walk from six to eight up Beacon Hill, and across some fields, to the village of Charlecombe, which is sweetly situated in a little green valley, as a village with such a name ought to be. Marianne is sensible and intelligent; and even Jane, considering how fair she is, is not unpleasant. We had a Miss North and a Mr. Gould of our party; the latter walked home with me after tea. He is a very young man, just entered Oxford, wears spectacles, and has heard that ‘Evelina’ was written by Dr. Johnson.”

- Outings: “There is to be a grand gala on Tuesday evening in Sydney Gardens, a concert, with illuminations and fireworks. To the latter Elizabeth and I look forward with pleasure, and even the concert will have more than its usual charm for me, as the gardens are large enough for me to get pretty well beyond the reach of its sound. In the morning Lady Willoughby is to present the colors to some corps, or Yeomanry, or other, in the Crescent, and that such festivities may have a proper commencement, we think of going to….”

11 June 1799 (Queen Square, Bath):

- Taking the waters: “Edward has been pretty well for this last week, and as the waters have never disagreed with him in any respect, we are inclined to hope that he will derive advantage from them in the end. Everybody encourages us in this expectation, for they all say that the effect of the waters cannot be negative, and many are the instances in which their benefit is felt afterwards more than on the spot.”

- Thoughts on “First Impressions”: “I would not let Martha read ‘First Impressions’ again upon any account, and am very glad that I did not leave it in your power. She is very cunning, but I saw through her design; she means to publish it from memory, and one more perusal must enable her to do it.”

15 June 1808 (Godmersham)

- Details of their journey: “Which of all my important nothings shall I tell you first? At half after seven yesterday morning Henry saw us into our own carriage, and we drove away from the Bath Hotel; which, by the by, had been found most uncomfortable quarters,—very dirty, very noisy, and very ill-provided. James began his journey by the coach at five. Our first eight miles were hot; Deptford Hill brought to my mind our hot journey into Kent fourteen years ago; but after Blackheath we suffered nothing, and as the day advanced it grew quite cool.

- A rest for breakfast: “At Dartford, which we reached within the two hours and three-quarters, we went to the Bull, the same inn at which we breakfasted in that said journey, and on the present occasion had about the same bad butter. At half-past ten we were again off, and, travelling on without any adventure reached Sittingbourne by three. Daniel was watching for us at the door of the George, and I was acknowledged very kindly by Mr. and Mrs. Marshall, to the latter of whom I devoted my conversation, while Mary went out to buy some gloves. A few minutes, of course, did for Sittingbourne; and so off we drove, drove, drove, and by six o’clock were at Godmersham.”

25 April 1811 (Sloane St.)

- Possible publishing date for Sense and Sensibility: “No, indeed, I am never too busy to think of S. and S. I can no more forget it than a mother can forget her sucking child; and I am much obliged to you for your inquiries. I have had two sheets to correct, but the last only brings us to Willoughby’s first appearance. Mrs. K. regrets in the most flattering manner that she must wait till May, but I have scarcely a hope of its being out in June. Henry does not neglect it; he has hurried the printer, and says he will see him again to-day. It will not stand still during his absence, it will be sent to Eliza.”

6 June 1811 (Chawton)

- New set of dishes: “On Monday I had the pleasure of receiving, unpacking, and approving our Wedgwood ware. It all came very safely, and upon the whole is a good match, though I think they might have allowed us rather larger leaves, especially in such a year of fine foliage as this. One is apt to suppose that the woods about Birmingham must be blighted. There was no bill with the goods, but that shall not screen them from being paid. I mean to ask Martha to settle the account. It will be quite in her way, for she is just now sending my mother a breakfast-set from the same place. I hope it will come by the wagon to-morrow; it is certainly what we want, and I long to know what it is like, and as I am sure Martha has great pleasure in making the present, I will not have any regret. We have considerable dealings with the wagons at present: a hamper of port and brandy from Southampton is now in the kitchen.”

13 June 1814 (Chawton)

- Thoughts on Mansfield Park from Mr. and Mrs. Cooke: “In addition to their standing claims on me they admire “Mansfield Park” exceedingly. Mr. Cooke says “it is the most sensible novel he ever read,” and the manner in which I treat the clergy delights them very much. Altogether, I must go, and I want you to join me there when your visit in Henrietta St. is over. Put this into your capacious head.”

23 June 1814 (Chawton):

- Travels and plans: “I certainly do not wish that Henry should think again of getting me to town. I would rather return straight from Bookham; but if he really does propose it, I cannot say No to what will be so kindly intended. It could be but for a few days, however, as my mother would be quite disappointed by my exceeding the fortnight which I now talk of as the outside—at least, we could not both remain longer away comfortably.”

- Friends go to Clifton: “Instead of Bath the Deans Dundases have taken a house at Clifton—Richmond Terrace—and she is as glad of the change as even you and I should be, or almost. She will now be able to go on from Berks and visit them without any fears from heat.”

23 June 1816 (Chawton)

- Bits of news: “My dear Anna,—Cassy desires her best thanks for the book. She was quite delighted to see it. I do not know when I have seen her so much struck by anybody’s kindness as on this occasion. Her sensibility seems to be opening to the perception of great actions. These gloves having appeared on the pianoforte ever since you were here on Friday, we imagine they must be yours. Mrs. Digweed returned yesterday through all the afternoon’s rain, and was of course wet through; but in speaking of it she never once said “it was beyond everything,” which I am sure it must have been. Your mamma means to ride to Speen Hill to-morrow to see the Mrs. Hulberts, who are both very indifferent. By all accounts they really are breaking now,—not so stout as the old jackass.”

June in Jane Austen’s Novels

Pride and Prejudice

- Lady Catherine to Elizabeth: “Oh, your father, of course, may spare you, if your mother can. Daughters are never of so much consequence to a father. And if you will stay another month complete, it will be in my power to take one of you as far as London, for I am going there early in June, for a week; and as Dawson does not object to the barouche-box, there will be very good room for one of you—and, indeed, if the weather should happen to be cool, I should not object to taking you both, as you are neither of you large.”

- June at Longbourn after Lydia’s departure: After the first fortnight or three weeks of [Lydia’s] absence, health, good-humour, and cheerfulness began to reappear at Longbourn. Everything wore a happier aspect. The families who had been in town for the winter came back again, and summer finery and summer engagements arose. Mrs. Bennet was restored to her usual querulous serenity; and by the middle of June Kitty was so much recovered as to be able to enter Meryton without tears…

- Lydia born in June: “Well,” cried her mother, “it is all very right; who should do it but her own uncle? If he had not had a family of his own, I and my children must have had all his money, you know; and it is the first time we have ever had anything from him except a few presents. Well! I am so happy. In a short time, I shall have a daughter married. Mrs. Wickham! How well it sounds! And she was only sixteen last June. My dear Jane, I am in such a flutter, that I am sure I can’t write; so I will dictate, and you write for me. We will settle with your father about the money afterwards; but the things should be ordered immediately.”

Mansfield Park

- Edmund’s letter to Fanny: “I have sometimes thought of going to London again after Easter, and sometimes resolved on doing nothing till she returns to Mansfield. Even now, she speaks with pleasure of being in Mansfield in June; but June is at a great distance, and I believe I shall write to her. I have nearly determined on explaining myself by letter. To be at an early certainty is a material object. My present state is miserably irksome.”

Emma

- Happenings in Highbury: “In this state of schemes, and hopes, and connivance, June opened upon Hartfield. To Highbury in general it brought no material change. The Eltons were still talking of a visit from the Sucklings, and of the use to be made of their barouche-landau; and Jane Fairfax was still at her grandmother’s; and as the return of the Campbells from Ireland was again delayed, and August, instead of Midsummer, fixed for it, she was likely to remain there full two months longer, provided at least she were able to defeat Mrs. Elton’s activity in her service, and save herself from being hurried into a delightful situation against her will.”

- An outing delayed: “It was now the middle of June, and the weather fine; and Mrs. Elton was growing impatient to name the day, and settle with Mr. Weston as to pigeon-pies and cold lamb, when a lame carriage-horse threw every thing into sad uncertainty. It might be weeks, it might be only a few days, before the horse were useable; but no preparations could be ventured on, and it was all melancholy stagnation. Mrs. Elton’s resources were inadequate to such an attack.”

- Mr. Knightley offers his strawberry fields: “You had better explore to Donwell,” replied Mr. Knightley. “That may be done without horses. Come, and eat my strawberries. They are ripening fast.”

Persuasion

- Elizabeth Elliot born: “Walter Elliot, born March 1, 1760, married, July 15, 1784, Elizabeth, daughter of James Stevenson, Esq. of South Park, in the county of Gloucester, by which lady (who died 1800) he has issue Elizabeth, born June 1, 1785; Anne, born August 9, 1787; a still-born son, November 5, 1789; Mary, born November 20, 1791.”

- A June sorrow: “And I am sure,” cried Mary, warmly, “it was a very little to his credit, if he did. Miss Harville only died last June. Such a heart is very little worth having; is it, Lady Russell? I am sure you will agree with me.”

June Dates of Importance

This brings us now to several important June dates that relate to Jane and her family:

Family News:

8 June 1771: Henry Thomas Austen (Jane’s brother) born at Steventon.

23 June 1779: Charles Austen (Jane’s brother) born at Steventon.

18 June 1805: James Austen’s daughter, Caroline, born.

Historic Dates:

18 June 1812: The United States declares war on Great Britain (War of 1812).

18 June 1815: The Duke of Wellington defeats Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo.

Writing:

3 June 1793: Jane Austen most likely writes the last item of her juvenilia.

June 1799: Austen most likely finishes Susan (Northanger Abbey).

Sorrows:

I’m happy to report that I found no major sorrows for the Austen family in the month of June throughout Austen’s lifetime.

Joyful June

This concludes our June ramble through Jane Austen’s life, letters, and works. There is always something fascinating to explore! Next month, we’ll discover all the important dates and events from July in Jane Austen’s World. Until then, you might join the Jane Austen’s House Museum virtual book club! You can click here for more: https://janeaustens.house/visit/whats-on/.

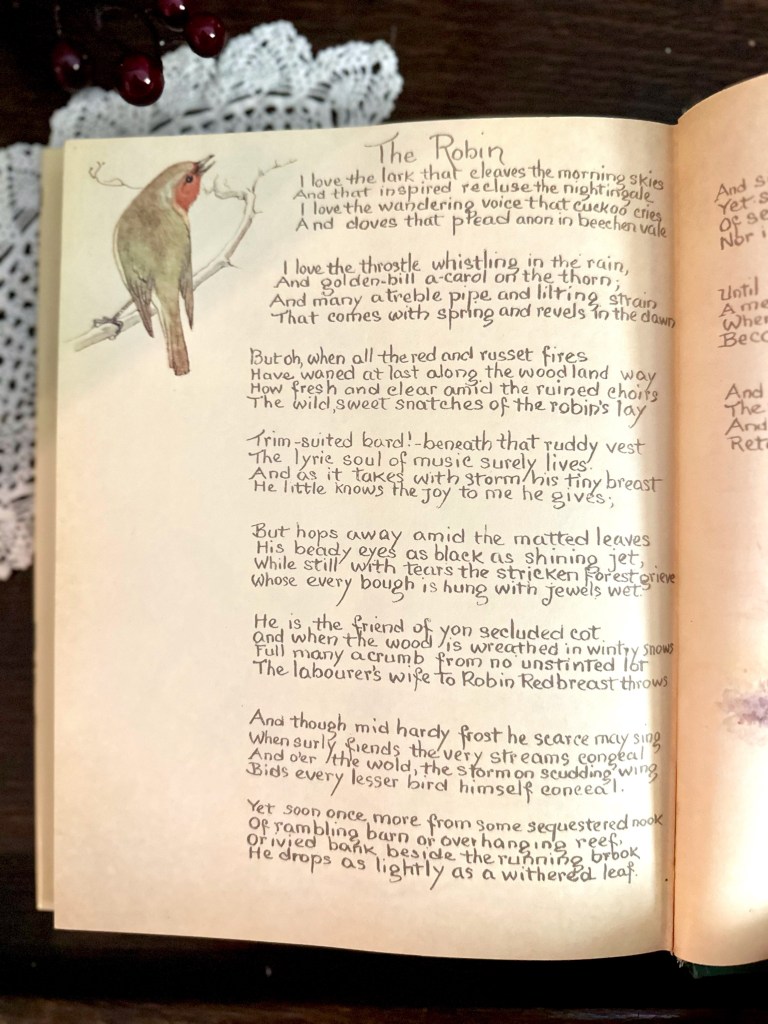

RACHEL DODGE teaches college English classes, gives talks at libraries, teas, and book clubs, and writes for Jane Austen’s World blog. She is the bestselling author of The Little Women Devotional, The Anne of Green Gables Devotional and Praying with Jane: 31 Days Through the Prayers of Jane Austen. Now Available: The Secret Garden Devotional! You can visit Rachel online at www.RachelDodge.com.