Part One of this four-part series left me salivating to meet Darcy’s aunt, for up to now we have experienced her only through Mr. Collins’s observations, which, the astute reader has come to surmise, MUST be suspect. After Lady Catherine de Bourgh’s daughter Anne stops by to visit Hunsford in her carriage, Charlotte announces to the group that they are invited to dine at Rosings. Even if Mrs. Collins hadn’t opened her mouth, Lizzy would have realized that something was up, what with an ecstatic Mr. Collins performing cartwheels and Irish jigs in the background and his chest puffed up with so much consequence and triumph that he nearly topples over from imbalance.

He cannot stop gloating about Lady CdeBs graciousness and affability, and pops up here and there like a Regency era whack-a-mole as the ladies and Sir William Lucas prepare for their walk to Rosings, constantly admonishing them with – “Lady CdeB wants this” – ” Lady CdeB expects that” – ” Lady CdeB says” — until he has Sir William and his daughter Maria quaking in their boots and practically passed out from fear.

Only Lizzy remains unperturbed. Mere stateliness of money or rank do not overly impress her, and this is one of the many reasons why this heroine, conceived in the late 18th century, retains her appeal over two hundred years after her conception. Her attitude is so modern that we readily understand the motives of this educated, independent-minded woman, who, despite having some serious socio-economic cards stacked against her (she has no legal rights under British law and her dowry is but a mere pittance), refuses to buckle under pressure or kowtow to Society’s dictates. Unlike many fictional heroines of her day, she will chance fate and wait for a man she can respect AND love. You go girl!

Much to our chagrin, Jane Austen continues to delay that first meeting between Lizzy and Mr. Collins’s benefactress. Jane first takes us over hill and dale to enjoy the beautiful vistas and prospects and forces us to listen to more of Mr. Collins’s blathering until we readers begin to skim-read with impatience. Then Rosings comes into view and Jane swiftly takes us inside the manse’s impressive entrance hall and to the room where Lady CdeB receives her visitors (the Hunsford party and us). Our hostess rises to greet us with great condescension and for a second we wonder if she might not be all that Mr. Collins promised. Much to our delight, the lady is MORE than was advertised. (Thank you, thank you, Ms. Austen.). Lizzy calmly takes in the scene and inspects Lady CdeB.

Lady Catherine was a tall, large woman, with strongly-marked features, which might once have been handsome. Her air was not conciliating, nor was her manner of receiving them such as to make her visitors forget their inferior rank.”

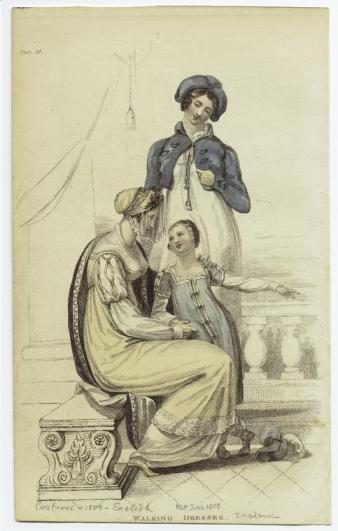

Lady CdeB much as I envision her in her younger years: Haughty and Handsome. Painting by Gainsborough.

In fact, the lady’s demeanor brought everything Mr. Wickham had said about her to Lizzy’s mind. Undaunted, Lizzy turns her inquisitive gaze upon the daughter, in whose pale, sickly, Gollum-like features and timid presence she finds nothing remarkable. Her inner bad-girl is immensely satisfied that such a mousy specimen is destined to become Mr. Darcy’s bride.

While Lizzy scarcely bats an eye at the sight of Lady CdeB, Sir William is unable to speak, his tongue cleaving to the dry roof of his mouth, while Maria is seriously considering rolling over and playing dead. Lady CdeB is more than happy to show off her silver and fine plate and chef’s talents to this humble group, for “the dinner was exceedingly handsome. ” This is about as detailed a description of outer appearances as Jane Austen ever gives. We have no idea of what the guests wore, what dishes were served, and how many servants were in attendance. Such details are unimportant in the grand scheme of Jane’s masterful study of the human character.

Mr. Collins is completely in his element, scraping and bowing and prattling while carving the meat, an honor he finds so great that it has eliminated any vestige of restraint. As he babbles nonstop, Sir William, having recovered his severe case of nerves, echoes the unfiltered stream of utterances. Lady CdeB laps up their compliments without a sense of irony. No Mr. Bennet she!

Lizzy, meanwhile, sits unnoticed on the side and twiddles her thumbs, waiting for an opening in the conversation. This fails to come, for Lady CdeB is too busy relating the opinions of “Me, Myself, and I”, an overpowering and determined trio intent on delivering their viewpoint on every subject.

In the drawing room Lady CdeB continues her one-sided discussions, giving Charlotte advice on all matters pertaining to household management, including the care of her poultry and cows, of all things. Then, just before poor Lizzy falls asleep from boredom, the Lady zeroes in on our heroine, firing off a series of questions.

- How many sisters do you have?

- Are they younger or older?

- Are they handsome?

- Any chance of them marrying soon?

- Are they educated as a young lady ought to be?

- What is your mother’s maiden name?

- What year and make is your father’s carriage?

Lizzy hides her outrage but feels all the impertinence of this inquiry. Lady CdeB attempts to rattle her again. “Your father’s estate is entailed on Mr. Collins,” she drops, before abruptly switching the topic. Seasoned interrogators use this technique to catch their subjects off guard, but our Lizzy remains unflappable:

“Do you play and sing, Miss Bennet?”

“A little.”

“Do your sisters play and sing?”

“One of them does.” (Mary. Hah!)

Undeterred, Lady CdeB keeps the chandeliers spotlighted over Lizzy’s head and continues her inquisition:

You ought all to have learned, the Miss Webbs all play.”

Still trying to rattle Lizzy’s chain, she resorts to insulting Mrs. Bennet’s mothering skills. The reader guffaws from the irony of it all.

“What, you don’t draw? Strange, but your mother should have taken you to town for the benefit of masters.”

“No Governess! How is that possible. You must have been neglected.”

And on and on she goes. Elizabeth plasters a polite smile on her face and refuses to cower. I recall reading this passage with the speed of a Ferrari on an open road racing to the finish. I so enjoyed the heady ride Jane Austen was taking us on that I had to read how it ended as swiftly as possible! (In fact, I finished my first reading of P&P in one sitting, then reread it a short time later, slowly savoring each word.)

Lady CdeB asks one more question —

Are any of your younger sisters OUT, Miss Bennet?”

“Yes, ma’am, ALL.”

“ALL?!!” You could have thrown the feathers on top of Lady CdeB’s aristocratic head for a loop when Lizzy calmly explains the fairness of her mother’s decision. “You give your opinion decidedly for so young a person, ” she sniffs, but the reader already knows the score:

Miss Elizabeth Bennet of Longbourn, One

Lady Catherine de Bourgh of Rosings, Zilch

GO TEAM LIZZY!”

After this scene one can only conclude that Lost in Austen got it right when the series transported Elizabeth Bennet to the future and had her land on her feet, embracing smart phones, automated teller machines, and iPads as if to the Internet born. In this time travel fantasy series the viewer can readily imagine Jane’s prototype of a modern heroine wanting to free herself from the restraints of her era. In my estimation, Lost in Austen lost its way when it followed the story line of boring Amanda Price discovering life in the past in favor of Lizzy’s more interesting journey into the future.

As for Lady CdeB, I will next examine her as a Proficient. Read Part One of the Lady CdeB series here.

Read Full Post »

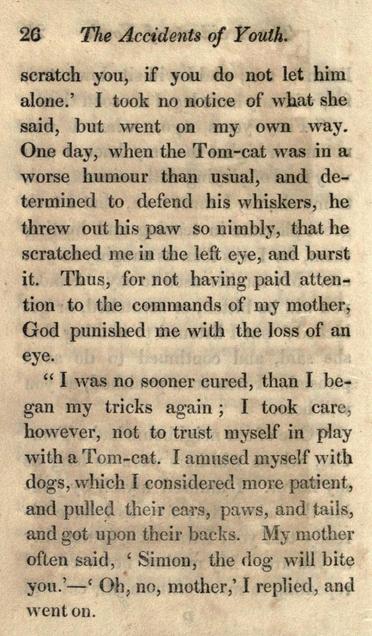

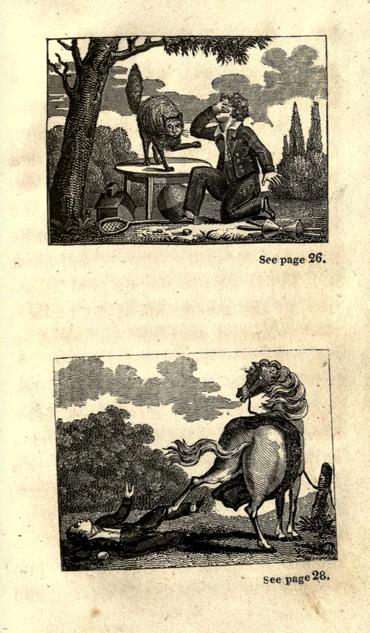

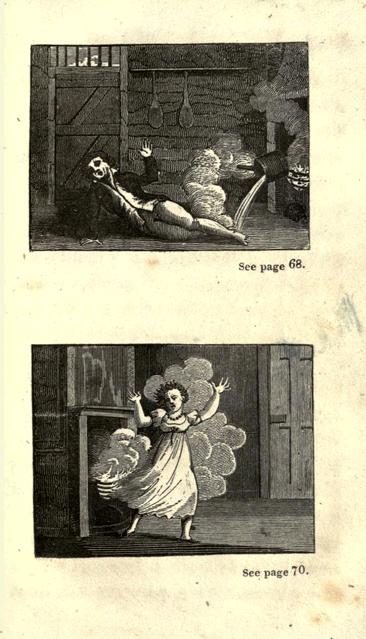

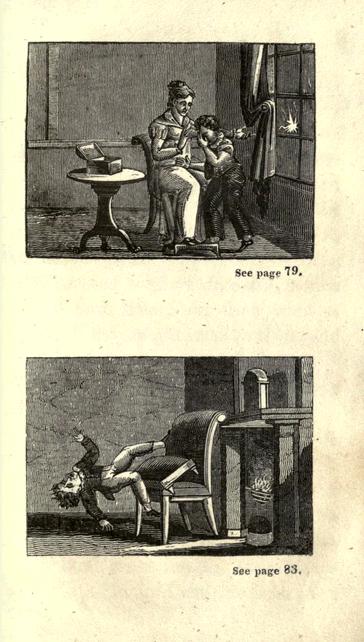

The final image in this post shows the danger of a broken glass window and a young boy falling from furniture that he had rearranged at play. Another, earlier book entitled The Blossoms of Morality and published in 1806, concentrates on the instruction of young ladies and gentlemen”. The stories include “Juvenile tyranny conquered” and “The melancholy effects of pride”. One can imagine that, after reading Fordyce’s Sermons to his young children, Mr. Collins would have picked up these books to read to his children.

The final image in this post shows the danger of a broken glass window and a young boy falling from furniture that he had rearranged at play. Another, earlier book entitled The Blossoms of Morality and published in 1806, concentrates on the instruction of young ladies and gentlemen”. The stories include “Juvenile tyranny conquered” and “The melancholy effects of pride”. One can imagine that, after reading Fordyce’s Sermons to his young children, Mr. Collins would have picked up these books to read to his children.