Inquiring readers,

Throughout 2025, our team – Vic Sanborn, Rachel Dodge, and Brenda Cox – will celebrate events and historical details during Jane Austen’s life (including the years just before and after).This year marks the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen’s birth on December 16th, 1775. She lived her short life during King George III’s reign. (Austen died in 1817, aged 41; the king died in 1820, aged 81.) Jane Austen Society organizations around the world will, in the next twelve months, mark this important year with their own celebrations and acknowledgments of her life and the events that influenced her talents.

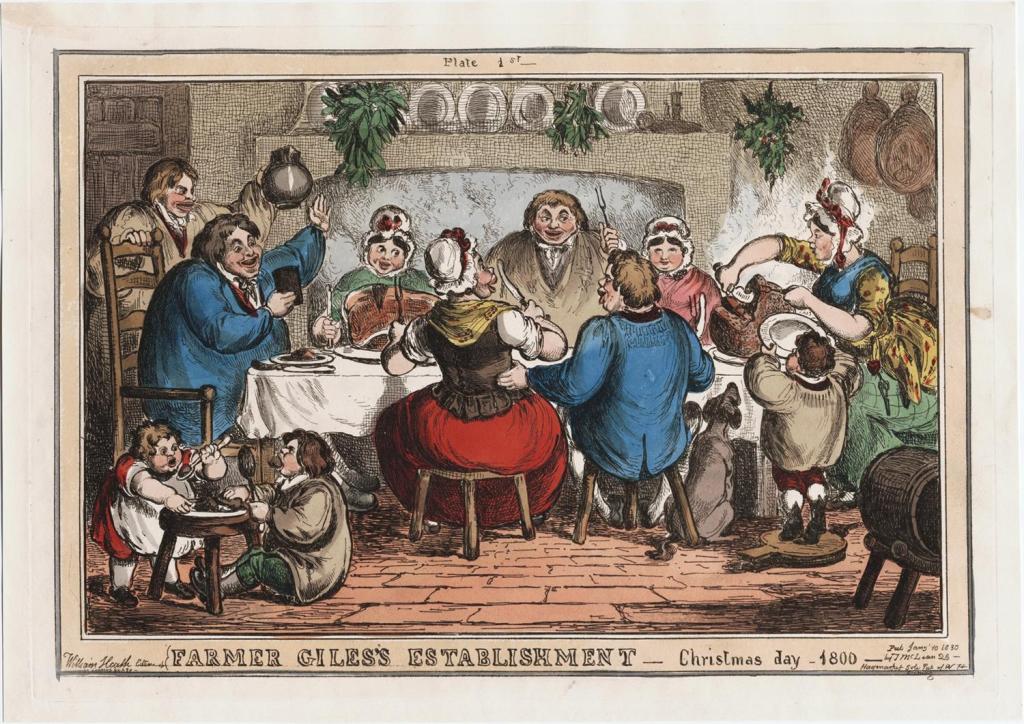

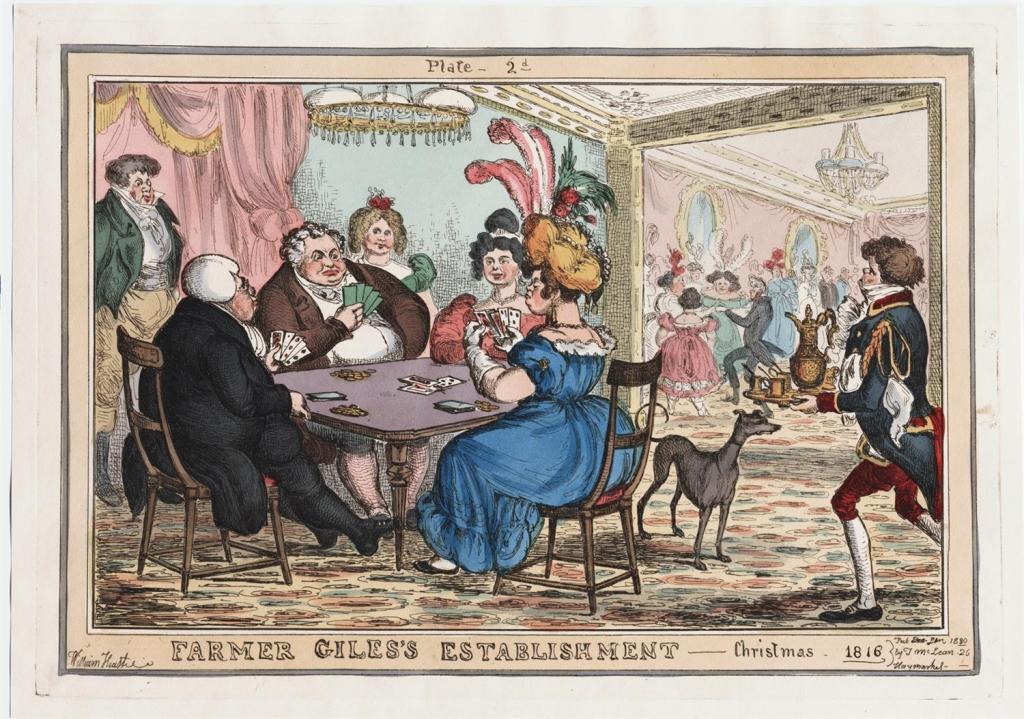

Most of us who have read about dining during the Georgian era learned about 18th C. dining etiquette largely through novels, films, and television shows that featured fabulous Aristocratic settings in high-ceilinged dining rooms, liveried servants at the ready to serve or take away plates, and tables laden with food in fine silver or porcelain dishes.

Lady Catherine de Bourgh’s dinner for Elisabeth Bennet and Mr Collins and Charlotte. Screen shot taken by Vic Sanborn

But how was British food celebrated among the other classes? How did British empire building affect what it meant to be British in terms of food tastes? Both of these topics will be addressed in this post by 1) renowned British food historian, Ivan day, and 2) Dr Sarah Fox, senior lecturer and researcher at Edge Hill University.

1) Dining and Hospitality in Eighteenth Century English Provincial Towns and Cities

In this YouTube video, Mr Day discusses the influences that changed dining and hospitality in 18th century Britain. French foods at court in the 1690s began to spread from British aristocrats to the provinces throughout the 1700s and into the 1780’s and 90’s, when Austen was a child.

English food preferences changed in remarkable ways, which Mr Day discusses in detail. This 36 minute video offers both closed captioning and a transcript.

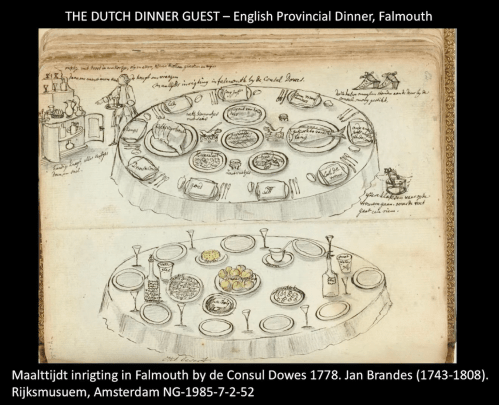

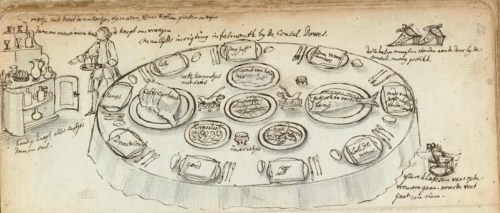

A few highlights of the talk that struck me include these drawings of a provincial English meal in Cornwall that were made in the 1770s by a visiting Dutch artist. He provided a marvelous snapshot of 18th C. dining.

Mr Day notes the details of these drawings, The details are remarkable. The pattens at the upper right were once worn to protect ladies’ shoes from mud. Only some vegetables were presented, with the emphasis still on eating meat. Notice the unique placement of a knife, fork and spoon to the right of the plates. A waiter holds a tray with wine glasses and points to a sideboard filled with more glasses, as well as decanters.

The second drawing shows a table laden with assorted sweets: cookies, almond biscuits, oranges, butter cream, and preserved cherries.

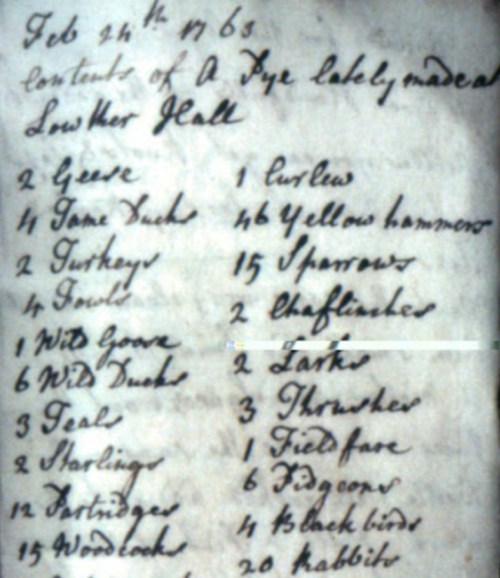

Another one of his observations intrigued me – that of an enormous English pie, labeled the Northern Country Great Pie in the video. James Lowther, the First Earl of Lonsdale House in Cumbria offered such a pie in 1763. It was the English aristocratic Christmas tradition to create this pie, meant to be eaten after dancing. Just imagine! The ball supper was served at 2 or 3 in the morning. Its size and weight of 22 stone (308 lbs.) must have been staggering, considering the list of baked animals that went into its making. This is a screenshot of half the list.

To view the entire list, click on this link entitled Eat the Entire Creation if You Dare, which sits on Mr Day’s blog, Food History Jottings. One can only read in awe at the amount of protein those animals contributed. These ball supper pies were not only large, but expensive, and most likely made from game hunted on the aristocrat’s land.

At the end of his video, Mr Day showed pie molds that resulted in exquisite creations. This link to raised pie molds at MichaelFinlay.com shows a pie made by Mr Day from the Harewood mould.

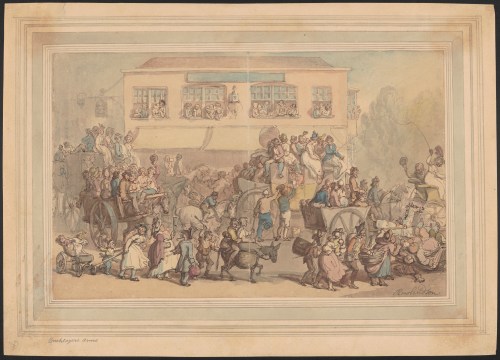

Smaller, often hand-held pies were consumed by all classes, especially the working classes and travelers. By 1775, the year of Jane Austen’s birth, these portable foods had become ubiquitous. Pies were made for long distance travel. They encased meat and fruits in a variety of pastries that helped food to last longer, an important feature in an age without refrigeration. In 17th and 18th century Britain…

“…pies were devices in many senses of the word. They were used to preserve food,…and to prevent rot. Perhaps in part because of their preservative functions, pies were well-traveled, sent to friends and family members across long distances. Pies were embedded within global foodways, filled with ingredients sourced from around the planet.” – Hearse Pies and Pastry Coffins: Material Cultures of Food, Preservation, and Death in the Early Modern British World, Amanda E. Herbert &Michael Walkden, 07 Sep 2023

These portable foods had a long and varied history, starting centuries ago with the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans. Recipes differed in each country, which did not diminish their popularity. Imagine being able to take food safely on long voyages, whether over land or sea, in an age when so many foods were consumed fresh.

The years between 1688 and 1815 were an important and exciting time for the British in terms of trade. Great Britain oversaw a sprawling empire during the Georgian era:

“Domestic industry [in England] flourished, with many workers pursuing dual occupations on a seasonal basis in industry and agriculture. English society contained a flourishing and more extensive middling sector than any other western country, including the Dutch Republic. This provided a strong platform for commerce with, and settlement in, far-flung territories.” – Symbiosis: Trade and the British Empire, Professor Kenneth Morgan, History, BBC.

Dr Sarah Fox, from Edge Hill University, examined the following topic:

2) Britishness revisited: food and the formation of British identities in the late eighteenth century.

Trade routes and the enormous reach of the British empire over the world began to change British attitudes towards food. Dr Fox discusses this topic in detail in the YouTube video below. This presentation also has closed captioning and a transcript. In this instance, I found both features useful, since, while Dr Fox’s research is fascinating, her rapid and soft-spoken speech is hard to follow. Still, this video is a worthwhile investment of time.

During what is now regarded as the long 18th century, which spans the Georgian era that either ended in 1815 after the Napoleonic Wars, or in 1830, which marks the death of King George IV (these dates are still under discussion), the British empire oversaw a dominant position among the major European trading empires.

At the end of this period, traders and merchant ships enabled the British to successfully expand beyond the boundaries of their island nation. They imported goods and foods from North America and the West Indies, Africa, the Carribean, and the East Indies. Closer to home they traded with Ireland, Germany, and Russia. Maps from The Guardian show the routes taken overseas in the 18th C. with densely criss crossed lines of travel.

King George III (‘Farmer George’)

As mentioned earlier, during her lifetime, Austen knew only one king. Her distaste of George III’s eldest son, the Prince Regent, is well known, and has been documented on this blog.

“George [III] was particularly interested and adept at farming. He felt strongly that he should use his lands to better feed the nation, and used Windsor and Kew to develop improvements in agriculture. He published his thoughts on more than one occasion, using the pseudonym ‘Ralph Robinson’.

George enlisted Sir Joseph Banks to smuggle merino sheep from Spain to breed them with British sheep. This flock of experimental sheep grazed under the Great Pagoda at Kew.

George would walk his fields and till the soil himself, often being mistaken for an ordinary gentleman. His nickname of ‘Farmer George’ endeared him to the public”. – Quote from George III, The Complex King, Historic Royal Palaces.

As it turned out, Farmer George had a simple, old-fashioned (but knowledgable) taste in cuisine. An article from the University College London (UCL) entitled “Chicken broth & lobster among 3,000 dishes served to King George III, 3 November 2023”, in which a research group, including Dr Fox, lists the top ten foods generally consumed by King George III. It is obvious his food tastes were quite conservative. They were:

Chicken broth, Sweet tarts, Roasted capon (similar to roast chicken), Roast mutton, Asparagus, Lobster, Spinach, Artichokes,Roast chicken, andRoast beef.

It’s fascinating to hear Dr Fox list the enormous amount of research regarding foods eaten during the Long 18th through datasets accumulated from meticulous records that were kept regarding household food consumption. Records that survived are available all over the UK. Ivan Day also benefited from such record keeping, which he shared in his video.

The typical British fare of the 18th century was not the only food ‘Farmer George’ and his family consumed. The king and queen occasionally dined on more exotic dishes during state occasions, including recipes based on French cuisine and foods brought in from the empire, such as those from the West and East Indies.

Like British pies, turtles also offered a portable solution for travelers. British sailors used turtles for fresh food. They could be transported alive in sea water and eaten when they were needed. The meat of a six pound turtle could feed quite a few men. Soon, turtles, once a preferred food for sailors, were prepared as an exotic food for aristocrats.

In 1744, Admiral of the Fleet, George Anson, brought two 300 lb turtles as gifts, one of which was given to the Royal Society’s Dining Club. From this time on, chefs created delicious dishes and soups from imported turtle meat. In fact, famed chef Marie-Antoine Careme, who created sumptuous banquets for the Prince Regent, thought turtle soup to be quite competitive with British roast beef! Fifty years after their introduction to British cuisine, turtles became a food mainstay for the British.

Captain George Anson, 1755, portrait by Joshua Reynolds.

Wikimedia Commons/National Portrait Gallery, London. Looking Through Art: Turtle Cuisine

Interestingly, George III, whose food tastes were traditional, ate only mock turtle soup made from a calf’s head, and had it served a mere fourteen times between 1788 and 1801. A JSTOR Daily article, Turtle Soup: From Class to Mass to Aghast, describes how turtle soup and mock turtle soup became accessible to the British middle classes. These tastes soon spread to the Continent and North America.

Meanwhile, the Prince Regent, who was more adventurous in his culinary explorations than his father, ate turtle meat at Carlton House at least once per week. He also embraced Eastern culture and built the Brighton Pavilion using Eastern motifs influenced by Eastern trade.

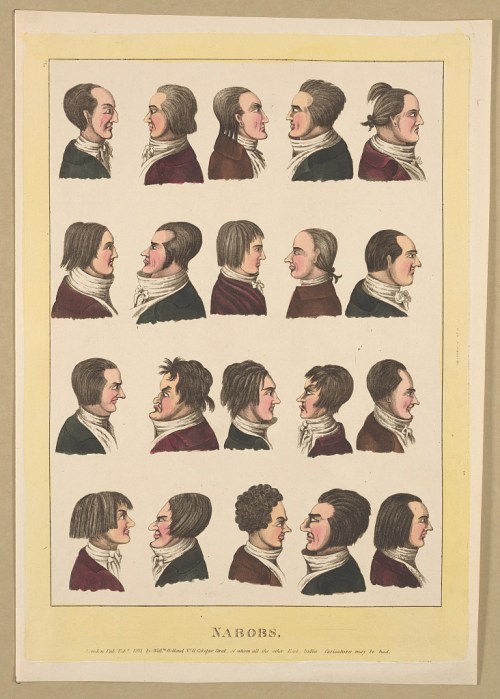

According to Dr Fox, the British adapted to the unfamiliar flavors and spices from the Far East more slowly than the foods from the West Indies. In addition, these spices were expensive. Nabobs, or British men who were employed in the East India Company, returned to Great Britain with their families, along with the fortunes they made in India’. They also brought with them their love of Indian spiced food. To many, these dishes were too hot and strong in flavor for British tastes — at first.

Print shows profile portraits of 20 men, called nabobs, who are representatives of the East India Company that have returned home with newly acquired wealth, generally through dubious or corrupt means.

Names: Holland, William, active 1782-1817, publisher. Library of Congress

In 1747, Hannah Glasse, cookbook author, published the first recipe for curry in her cookbook, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy. As Dr Fox relates, Glasse included rabbit plus onions, pepper, corn, rice, coriander seeds and butter in this edition. By 1751, she had replaced the rabbit with chicken. Then added new spices that included ginger, turmeric, lemon, and cream. Both the rice and coriander were removed. Due to the turmeric, this dish resulted in a bright yellow color. The recipe, adapted for British taste, was reproduced in a variety of cookbooks practically unchanged for years afterwards. As I understand, rice was added as a side dish to the changed cuisine. Glasse’s curry recipe was mild enough to satisfy British tastes.

While George III did not eat curry at all, in 1816, the Prince Regent was served a curry dish. From this period on, the British had, through trade and royal influences, adapted their taste towards foreign foods and spices. Today, over 12,000 curry houses are spread across Britain.

As a writer, Austen used food descriptions to characterize the people in her novels – Mr Woodhouse’s penchant for gruel; Mr Bingley’s lavish ball and a sumptuous supper meal afterwards, and Mrs Bennet’s two courses served for Mr Bingley and Mr Darcy. Her two courses most likely consisted of anywhere from 10 -25 dishes.

One can imagine how much Elizabeth must have cringed when her mother assured Mr Collins that they were able to keep a good cook, and that her daughters had nothing to do in the kitchen, (Pride and Prejudice, Chapter 13.) Austen’s use of food in her novels was sheer genius as she introduced her readers to absurdity and reality at the table!

Additional Resources:

Ivan Day

Spotify: The British Food History Podcast: 18th Century Dining, Ivan Day, January 2023

Ivan Day is a social historian of food culture and a professional chef and confectioner.

https://open.spotify.com/episode/22BHsKHncyk2i6UXEzcIY2

Issue 30: Cooking for the Georgians — Jane Austen Literacy Foundation

18th Century Autumn Pies, All Things Georgian

Sarah Fox

How Curry Conquered Britain, a short video by the BBC.

18th Century Curry Recipe – Beamish

Trade goods from the East: Spices | The East Indies | The Places Involved | Slavery Routes

Chicken broth & lobster among 3,000 dishes served to King George III | UCL News

About George III and George IV

The Royal Diets of George III and George IV | All Things Georgian

George III, the Complex King | Kew Palace

Regency Banquet is inspired by Antonin Carême – the original ‘celebrity chef’

About George III: Historic Royal Palaces: Kew Palace

Note:

Green sea turtles, whose popularity as a food slowly declined over the centuries, had been caught in such prolific numbers that in 1973 they were classified as endangered.

A short history of turtles as food, starting with seafarers in the early 18th century and culminating 50 years later, as turtle soup began to be closely associated with the British empire and British Identity. Turtle Soup: From Class to Mass to Aghast – JSTOR Daily