Emma was not inclined to give herself much trouble for his entertainment, and after hard labour of mind, [Lord Osborne] produced the remark of its being a very fine day, and followed it up with the question of: “Have you been walking this morning?”

“No my lord, we thought it too dirty.” (Unpleasant, stormy.)

“You should wear half boots.” After another pause: “Nothing sets off a neat ankle more than a half boot; nankeen galoshed with black looks very well. Do not you like half boots?”

“Yes; but unless they are so stout as to injure their beauty, they are not fit for country walking.” – Jane Austen, The Watsons

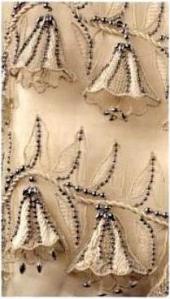

Ladies shoes were quite delicate in Jane Austen’s day. They were made of satin or soft kid leather, and thin soles with short heels. Kid leather was a soft and pliable leather made from young goat skin that was often used for slippers (and gloves as well). Shoes made from kid leather could be dyed or embroidered, but the thin flimsy material could barely withstand ordinary wear and tear, much less rough treatment.

During the mid-Regency, tied shoes went out of fashion as lace-up half-boots became popular for outdoor wear. Made of leather or nankeen (a durable natural cotton from China, with a distinct yellow color), these boots were more geared for long walks in the country than the delicate slippers they replaced. But the boots were deceptive, for the leather was quite thin by today’s standards and tore and scuffed easily or were quickly ruined by the elements. As a general rule, thick leather shoes with sturdy wooden soles were worn by laborers. The ruling classes, it was felt, needed no such rough and tumble items.

Although still a minority in women’s footwear at the beginning of the 19th century, ankle boots would become the dominant style of daytime footwear by the 1830s. This early pair of fashionable boots shoes shows the importance of angular lines, repeated throughout designs and evident from what ever position the boots are viewed. The museum also possesses a similar boot with a small “Italian” heel (2009.300.1487), demonstrating the overlap in styles. The original shoelaces, unlike those now in the boots, would have most likely matched the dark teal color of the leather. – Met Mus collection database

Boots began to become fashionable for women in the last quarter of the 18th century, but their use was limited primarily to riding and driving. Few pairs survive, and the peculiar wrap-around leg on this example is specific to this period and extremely rare. Although not well-fitted enough to provide a particularly secure fastening to the foot, the wrapped leg may have been intended to provide superior protection from dust and moisture than the standard laced closure. Colored footwear was a favored means of complimenting plain white dresses in the early 19th century, and the dark teal blue color seen here seems to have been particularly favored.- Boots

In the early years of the 19th century boots gradually became acceptable for women. By 1804, half-boots with front lacing and ribbon trimmings, like this pair, had started to appear in fashion illustrations for ‘walking’ or ‘morning’ dress. Hardwearing cottons – the striped uppers are made of cotton jean – became increasingly available and were used as alternatives to leather. Heroines in novels by Jane Austen (1775-1817) are often described wearing footwear of this kind. V&A

Toughening Nankeen for rough wear and tear: To Wash- Put a handful of salt into a vessel with a gallon of cold water immerse the nankeenm and let it remain for twenty four hours; then wash it in hot lye without soapm and hang up to dry without wringing it, Nankeen washed in this manner will keep its colour for a long time – The Dictionary of Daily Wants, 1866