Copyright (c) Jane Austen’s World.

Hear what a male writer has observed on the fashion of exposing the bosom! A woman, proud of her beauty, says he, may possibly be nothing but a coquet: one who makes a public display of her bosom, is something worse.” – The Mirror of Graces, by A Lady of Distinction, 1811, p. 120

Could the above statement possibly be true in light of our modern assumptions that the Georgian bossom was displayed in all its soft glory for all to see?

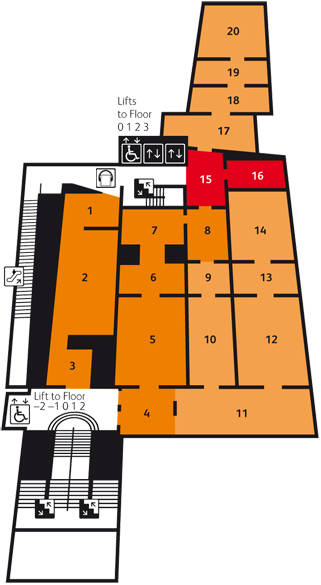

Waiting on the ladies

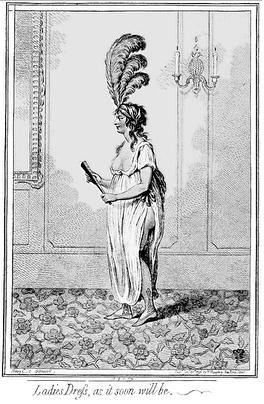

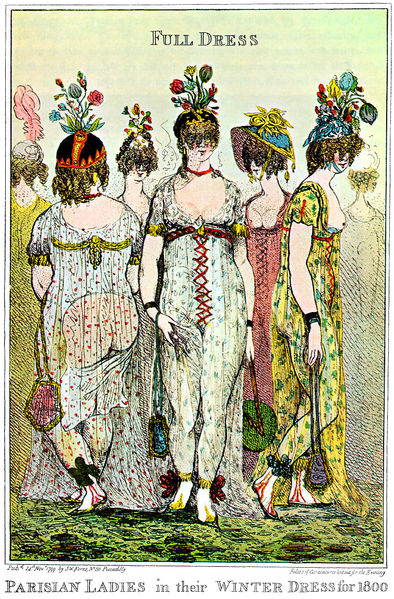

Our modern perception is heavily influenced by the caricatures of the period that make fun of unrestricted Regency gowns. But how much did contemporary cartoonists exaggerate? And what sort of woman would have exposed her bosom to such an extent that she would have been regarded as worse than a coquet? To be fair, the above image depicts a time (the 1820s) when the waist had gone as high as it could go under a woman’s bosom, skirts had widened and become conical shaped, and hems were festooned and decorated and shortened to reveal slippers and ankles.

Regarding the bosom, the proof is in the pudding, and the best way to assuage our curiosity is to view contemporary examples year by year.

From left, upper row: 1794-1795 walking gowns. 1795-1800 round gown. From left, lower row: 1797 Countess of Oxford. 1798, round gown.

Gentle reader, as you peruse the gallery of images, please look for a pattern. You shall begin to see a distinction between day and evening dress, regardless of the time of year.

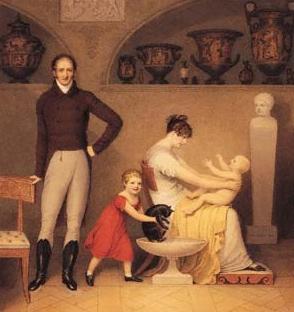

1st column, top: 1800, Salucci family. Bottom: 1800 V&A gown. 2nd column, top: 1801 April day gowns. Bottom: 1801 Marie Denise Villiers

While I believe that a variety of cleavages were on display during the Regency era (and I shall delve more into this topic later), the top left portrait of Mrs. Salucci is one of the few instances in which a shadowed cleavage is clearly painted or drawn.

1802 Bosoms. Top right: Princess Augusta. Other two images from Ladies Monthly Museum.

Why is this? One can safely assume that a voluptuous woman with large breasts, even when wearing a dress with a modest neckline, would reveal some cleavage. Thin girls or women with small bosoms would not have as much difficulty following the rules of decorum. Before the 20th century, the feminine ideal was a woman whose curves were bounteous and whose figures were pleasingly plumb. Rich husbands and fathers were proud to show off their well-fed women. Only the poor, who toiled all day and never had enough to eat, or the sick, or those who were metabolically overchallenged, were thin and scrawny. Thus, it made sense that during the Regency heaving bosoms were de rigueur. But were they?

In this image I have included both French, English, and American gowns. Left to right, clockwise, starting at the top. 1803, Costume Parisien. 1803, Mirroir de la Mode. 1805, American neoclassical gown. 1805, English cotton muslin, Kyoto costume Institute. 1804, three French Promenade dresses.

Regardless of nationality, a woman could choose to be as modest (or daring) as she liked. As far as I can tell from fashion images and portraits, modesty won hands down. High necklines, chemisette inserts, and high collars ruled the day. But night provided a different story.

1806 gowns. Top left, Binney sisters. Top right, Opera and drawing room gowns. Bottom image, Lady Codrington.

In the above composite image of 1806 gowns, more of the bosom is revealed than in previous images. Consider the sources. The Binney sisters and Lady Codrington, who were sitting for their portraits, would have chosen their best gowns to wear. Full dress, or evening dress, revealed more skin. The third image also depicts evening wear. In those two images you can more readily understand why empire gowns created such a stir at first:

Observers of the period frequently deplored the absence of modesty conveyed by a style that was predicated on the prominence and exposure of the breasts and on the barely veiled body….Sheer, narrow dresses … caused a sensation at the beginning of the nineteenth century, more because of their contrast with the elaborate hooped costumes of previous decades than for any real immodesty. – Source: Two dresses [French] (1983.6.1,07.146.5) | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

1807 Regency gown fashion plates

By now you have seen enough examples to have noticed a trend. Examine the above fashion plate images. Which necklines belong to full dress, or evening gowns, and which belong to day gowns or walking gowns? Of the five necklines, only the top left can be construed as revealing. And this neckline, depending on the size of the woman’s breasts, could be both modest or plunging.

1810 Regency gowns

The 1810 Regency gowns demonstrate a variety of necklines and layers of clothing. As in Cassandra’s portrait of Jane Austen, chemissetes were widely used. Fichus, shawls, tippets, and pelerines were also popular. The widow in the evening mourning gown (top middle) wears a cross that lies inside her cleavage. The white embroidered gowns (top right and lower left) demonstrate how the neckline is determined by whether the gown is worn for day (top right) or for evening (lower left, image of French gowns, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Jane Austen by Cassandra, 1810

In the image painted by Cassandra, Jane wears a simple gown, much like the Binney sisters were wearing. You can observe her chemisette under the low neckline, which created a more modest look for day time.

Regency gowns, 1811-1814

Princess Charlotte’s 1814 bellflower court gown (lower right), while breathtaking, did not reveal her bosom. The image of the 1812 full dress (second from top on the left) is a bit misleading, for the decorative drooping elements give the illusion that the neckline is lower than it actually is. (In this example, it is hard to see the line of the silk fabric running across the top.) The other day gowns cover the torso quite modestly.

1815-1816 Regency Gowns

The high necklines of the 1815 morning gown at top left and Mrs. Jens Wolff’s 1815 satin dress at top right would make a Quaker lady proud. The two 1816 evening gowns show a relatively modest neckline (lower left) and one that could be quite daring (lower right).

Until now I have not discussed the role that corsets played in propping up the bust line. Regency stays, which were darted and laced in the back, were quite short and were much less constricting than earlier Georgian models that cinched in the waist. The purpose of the Regency stay was to support a woman’s bust and create the distinctive Regency “shelf” silhouette.

1819 stays (short on left, long on right with inserted busk). Image @ Kyoto Costume Institute

A rigid wood or bone busk, which served to separate the breasts and encourage good posture, was inserted in the stays (or corseted petticoat).

1810 German copy of James Gillray's cartoon. The lady inserts her busk as her maid ties her stays.

Busks might provide one explanation of why so few drawings and paintings of the era depict a deep, shadowed cleavage, for the breasts were splayed aside. The busks were often hand-carved and decorated by a woman’s sweetheart. The exerpt from a poem entitled: On a Juniper Tree, cut down to make Busks, waxes eloquently about the tree’s sacrifice for beauty.

She cut me down, and did translate,

My being to a happier state.

No martyr for religion died

With half that unconsidering pride;

My top was on that altar laid,

Where Love his softest offerings paid:

And was as fragrant incense burned,

My body into busks was turned:

Where I still guard the sacred store,

And of Love’s temple keep the door.

1817-1820 dresses

By 1817, the stark neoclassical outlines of empire gowns at the turn of the century had given way to a fancier more decorative outline, in which embellishments were added both at the top of the gown and at its hem. The 1817 portrait of Princess Charlotte (top left) is bittersweet, for she died in fall of that year in childbirth. Once again, the popular princess fails to exhibit her cleavage.

Rolinda Sharples’ painting of the cloak room at Clifton Assembly Rooms (top right) shows a woman with a small bust wearing a low décolleté ball dress. Countess Blessington (second from bottom, left) also wore a daring neckline for her sitting for her portrait by Thomas Lawrence. The two evening gowns at the bottom are modest, and the 1820 beige walking dress with its high ruff neck demonstrates the Tudor influences in dress embellishments. Also note the lowered waistline.

1823-1825 dresses

By 1823, Jane Austen had been dead for six years. She would have been shocked to see how many furlebows, tucks, rows of lace, and ribbons decorated ladies gowns. At this time, the waistline was gradually lowering back to its natural position. Gone was the neoclassical Regency empire silhouette. Note how the three ball gowns shown in this series of images provide hardly any chance for a lady to show off her cleavage.

One can see the hint of shadow of the woman’s breasts in the large 1823 La Belle Assemblee image in the center and how the artist accommodated the influence of the busk. I included the plain every day green 1825 American gown to show the kind of dress an ordinary woman would sew for herself and wear.

I hope this post has cast a light on a Regency lady’s bosom. A Lady of Distinction wrote in 1811:

Let the youthful female exhibit without shade as much of her bust as shall come within the limits of fashion, without infringing on the borders of immodesty. Let the fair of riper years appear less exposed. To sensible and tasteful women a hint is merely required.”

A tasteful hint? I can only conclude that exposing too much of one’s bosom was not considered lady-like behavior. Thin and small breasted women experienced an easier time following society’s strictures. The well-endowed had a tougher row to hoe, although an enterprising young virgin could always insert a handy nosegay to hide her feminine bounty or add a pretty bow or a lace embellishment at the precise spot where a gentleman’s eyes should not stray.

Brazen hussies, light skirts, and women of easy virtue could bare as much skin as they pleased, having no reputation to protect. A very rich matron, whose place in society was secure, might be tempted to show more of her bosom than was prudent, but even she would refrain from displaying too many of her feminine allures before she was married!

Next, I will discuss heaving bosoms in Regency films and on book covers, and how the two media have influenced our perception of Regency bustlines.

More on the topic:

Read Full Post »

![twinings[1]](https://janeaustensworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/twinings1.jpg?w=249&h=300)