Emma, Lady Hamilton is best known by the casual history fan for her love affair with Lord Nelson. Born in poverty, she first plied her alluring wares in a brothel before becoming Sir Harry Fetherstonhaugh’s mistress. When she became pregnant, he unceremoniously dumped her. But Emma was too stunningly beautiful to live a life of squalor, and the Honorable Charles Greville next picked her to become his mistress. It was through Greville’s connections that she met painter, George Romney, whose obsession with her beauty resulted in a score of memorable paintings. (He continued to paint her portrait even after she left England.)

Emma loved Charles, but he needed money, so when he met a woman of means in 1786, he trundled Emma off to his widowed uncle in Naples, Italy, and thus Emma’s association with Sir William Hamilton began. Sir William was a diplomat and an avid art collector of classical statuary, urns and vases, which filled his villa in Portici overlooking the Bay of Naples. A connoisseur, he deeply appreciated Emma’s beauty, intelligence and special talents, not the least among which were her acting skills, hostessing abilities, and aptitude for learning new languages.

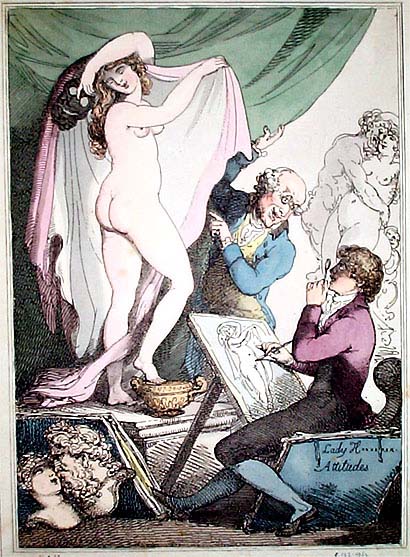

Emma’s stint as Romney’s model had given her experience posing in various classical guises. She’d also had the dubious distinction earlier in her career in London, of having worked as a scantily clad model and dancer – or “Goddess of Health” – at Dr. Graham’s Temple of Health and Hymen, which claimed to cure the reproductive and sexual problems of couples. Emma used her “theatrical” experiences to develop her “Attitudes”. In helping Emma design her act, Sir William, whose knowledge of the imagery on classical vases was authoritative, used ancient Roman pantomimes as a model. The result of their collaboration was a silent performance that combined poses, classical dance and acting with Emma’s special allure. Emma gave her first showing in spring of 1787 to a group of European guests. Sir William held the lights and introduced his wife, as he would do for all her theatrics.

The poses were an immediate hit. Emma moved through her routine within a tall black box surrounded by a gold picture frame, using only a shawl or urn for a prop. (Although she must have occasionally used a child, as included in these images.) For her “Attitudes”, Emma wore simple white-draped garments that fitted loosely and allowed her long hair to flow free. Her dresses were modeled on those worn by peasant women in the Bay of Naples. Sitting, standing, leaning, or kneeling, or posing as Medea or Cleopatra, she seemed to step right off the antique vases that her husband collected.

Emma’s repertoire was large and made up of at least 200 poses. During a performance she moved from one silent tableau to the other with great rapidity, delicacy. and deliberateness in what one writer termed ‘bursts of stillness.’ The private and select audiences would attempt to guess the names of the classical characters and scenes from stage and literature that she pantomimed, and stare in awe at Emma’s ability to transform her moods and the scene in an instant. Out of necessity, earlier viewings remained private, for Sir William and Emma were not married.

The couple did eventually marry in London in 1791 at St. George’s Church in Hanover Square. Sir William was 61 and his wife was 26. After their wedding, the Hamiltons returned to their home in Italy. They continued to perform the “Attitudes, but now they could publicly and conspicuously invite a much larger and more diverse audience. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the German poet, had been invited to watch a performance during a visit to Naples. Impressed, he wrote:

The Chevalier Hamilton so long resident here as English Ambassador, so long too connoisseur and student of Art and Nature, has found their counterpart and acme with exquisite delight in a lovely girl, English, and some twenty years of age. She is exceedingly beautiful and finely built. She wears a Greek garb becoming her to perfection. She then merely loosens her locks takes a pair of shawls, and effects changes of postures, moods, gestures, mien, and appearance that make one really feel as if one were in some dream. Here is visible complete and bodied forth in movements of surprising variety, all that so many artists have sought in vain to fix and render. Successively standing, kneeling, seated, reclining, grave, sad, sportive, teasing, abandoned, penitent, alluring, threatening, agonised. One follows the other and grows out of it. She knows how to choose and shift the simple folds of her single kerchief for every expression, and to adjust it into a hundred kinds of headgear. Her elderly knight holds the torches for her performance, and is absorbed in his soul’s desire.

There must have been something titillating and erotic about Emma’s act, for her poses, although inspired by classical motifs, also drew upon her earlier experiences as a “Goddess of Health” in London and her erotic performances dancing naked for Sir Harry Fetherstonhaugh’s friends on his dining table. Her fame spread far and wide, and Emma, Lady Hamilton’s “Attitudes” became a big draw on Europe’s Grand Tour. Painters and writers sought out her performances, which charmed aristocrats and royals as much as artists and the literary set. Élisabeth-Louise Vigée-Le Brun observed:

“Nothing was more curious than the faculty that Lady Hamilton had acquired of suddenly imparting to all her features the expression of sorrow or joy, and of posing in a wonderful manner in order to represent different characters. Her eyes alight with animation, her hair strewn about her, she displayed to you a delicious bacchanale, then all at once her face expressed sadness, and you saw an admirable repentant Magdalene.” – Elizabeth Vigee-Lebrun

The black and white Rehberg illustrations featured in this post and commisioned by Sir William, are drawn with simple, graceful and classical lines and freeze a particular “Attitude”. Their idealistic poses are among the few visual reminders that remain of Emma, Lady Hamilton as a performance artist. As the images show, Emma was a voluptuous, well-formed and beautiful woman. Her love for food and drink was no secret, and she would gain a substantial amount of weight over time, until at 47 she was described as being fat. But for a number of magical years, art, performance and beauty combined to create a series of tableaus that are still remembered today for their freshness and originality.

Read about Lady Hamilton’s later years and sad death in this link.

To learn more about Emma’s fascinating skills, watch a lecture by John Wilton-Ely. His talk is on the ” performances by Lady Emma Hamilton, one of the most celebrated beauties of her era and a remarkable pioneer in developing performance art.” Click here to watch the lecture. (A little over an hour long but well worth the time.)

More on the topic: