Inquiring Readers,

In the age of increasing AI domination, it has become easier to find quick facts about Jane Austen and the age in which she lived on the internet. Yet, as many of us have learned, AI scrapes information willy nilly from online sites, regardless of whether those facts are accurate or not. At first I was caught flat-footed. Not being a JA scholar, but a devoted reader about her life, I sadly used some of those wrong facts, but I learned quickly. I now have some tricks up my sleeve – I study original sources from the memories of scholars and family members who knew her personally or lived during her age, as well as from the people who survived her and recalled their memories of her well into their old age. I also purchase books from Austen renowned scholars and academics (but a few of their books will be listed in another post.)

I found out-of-print books in antique book stores in England, Boston, New York – whichever city I visited or lived in. But these treasures could be quite expensive. I discovered Thrift Books and ABE Books online, which sell histories and biographies also out-of-print for an affordable price. Better yet, I discovered The Internet Archive and Project Gutenberg years ago. They’re akin to searching libraries and their catalogues of precious books on your computer.

I found Project Gutenberg first. When I began JAW, I could print any chapters I needed for research, or cut and paste quotes for my blog posts. At the time, this service was around 38 years old. It’s a rather old-fashioned site for today, but extremely useful nevertheless. Better yet, all their books are copyright free!

The Internet Archive (IA) is another online site in which most books, newspapers, and videos can be “borrowed” for free once you sign in. Once you borrow the book, you can return to it at a later time to continue your research. IA resides on a later platform, so it might be more appealing to younger users.

Below are some books easily accessed online. A few choices echo the precious books I purchased for my library. Enjoy!!!

About Project Gutenberg

https://www.gutenberg.org/about/

https://www.gutenberg.org/about/

Project Gutenberg is an online library of more than 75,000 free eBooks.

Michael Hart, founder of Project Gutenberg, invented eBooks in 1971 and his memory continues to inspire the creation of eBooks and related content today.

Since then, thousands of volunteers have digitized and diligently proofread the world’s literature. The entire Project Gutenberg collection is yours to enjoy.

All Project Gutenberg eBooks are completely free and always will be.

PG documents can be printed, or one can easily copy and paste sections.

The Books: Jane Austen

Memoir of Jane Austen by James Edward Austen-Leigh, 1871 edition

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/17797/17797-h/17797-h.htm

About this book…

[This] Memoir of my Aunt, Jane Austen, has been received with more favour than I had ventured to expect… [In this Second] Edition, the narrative is somewhat enlarged, and a few more letters are added; with a short specimen of her childish stories. The cancelled chapter of ‘Persuasion’ is given, in compliance with wishes both publicly and privately expressed. A fragment of a story entitled ‘The Watsons’ is printed; and extracts are given from a novel which she had begun a few months before her death; but the chief addition is a short tale never before published, called ‘Lady Susan.’ – J. E. Austen-Leigh

Jane Austen, Her Life and Letters: A Family Record, by William Austen-Leigh and Richard Arthur Austen-Leigh (RA A-L), 1913.

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/22536

About this book…

The Memoir [by JE Austen-Leigh] must always remain the one firsthand account of her, resting on the authority of a nephew who knew her intimately and that of his two sisters. We could not compete with its vivid personal recollections; and the last thing we should wish to do, even were it possible, would be to supersede it. We believe, however, that it needs to be supplemented, not only because so much additional material has been brought to light since its publication, but also because the account given of their aunt by her nephew and nieces could be given only from their own point of view, while the incidents and characters fall into a somewhat different perspective if the whole is seen from a greater distance. Their knowledge of their aunt was during the last portion of her life, and they knew her best of all in her last year, when her health was failing and she was living in much seclusion; and they were not likely to be the recipients of her inmost confidences on the events and sentiments of her youth.- W A-L and RA A-L

Jane Austen and Her Works by Sarah Tytler, 1880

This book was …

“Written by Scottish novelist, Henrietta Keddie, who wrote under the pseudonym Sarah Tytler. Keddie was known for her depictions of domestic realism within her work, becoming very popular with women.

This work is a study of Jane Austen and her writings, with chapters on the life of Jane Austen and her novels, as well as extracts from some of her most famous works. This includes chapters of Pride and Prejudice, Northanger Abbey, Emma, Sense and Sensibility and Persuasion.- Rooke Books (First Edition – £675.00)“ https://www.rookebooks.com/1880-jane-austen-and-her-works

The book is also available on the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/janeaustenherwor00tytlrich/page/n9/mode/2up

About the Internet Archive

The Internet Archive, a 501(c)(3) non-profit, is building a digital library of Internet sites and other cultural artifacts in digital form. Like a paper library, we provide free access to researchers, historians, scholars, people with print disabilities, and the general public. Our mission is to provide Universal Access to All Knowledge.

916 billion web pages

49 million books and texts

13 million audio recordings (including 268,000 live concerts)

10 million videos (including 3 million Television News programs)

5 million images

1 million software programs

Anyone with a free account can upload media to the Internet Archive. We work with thousands of partners globally to save copies of their work into special collections.

Jane Austen

The Jane Austen Companion, by J. David Grey, Managing Editor; A. Walton Litz, and Brian Southam, Consulting Editors; H. Abigail Bok, 1986, New York: Macmillan.

https://archive.org/details/janeaustencompan00grey

This Book’s Introduction…

…”we have aimed at an encyclopedic book that will be of value to both the specialist and the general reader…individual essays, which appear in alphabetical order, cover a great variety of subjects: the life of Jane Austen and her family; the manners and literary tastes of her time; the composition of her fictions and their critical histories; the language and form of the novels; and many more…subjects that may strike some readers as arcane or antiquarian [are] “Characterization” and “Servants,” “Romanticism” and “Auction Sales,” “Education and “Gardens.” are all topics that will be of interest to many readers…This volume speaks with the many voices of Jane Austen’s contemporary voices.

Jane Austen: her biographies and biographers – or, ‘‘Conversations minutely repeated.’ Deirdre Le Faye, Jane Austen Society, Report for 2007

https://archive.org/stream/austencollreport_2007/AustenReport%202007_djvu.txt

About this talk…

This is an edited version of a talk given first at University College, London, on 15

November 2003, and then again to the Bath and Bristol Group on 29 April 2006

…The only sources of contemporary written information about Jane Austen that we have…are primarily her own letters – but these were not published till many years after her death, and even then only emerged gradually from 1870 up to the second half of the twentieth century.

Secondly, there are letters and pocketbooks originating in an outer circle of relatives and friends; some of the former were published by R.A. Austen-Leigh in Austen Papers, but many more remain as yet unpublished. These, and especially the pocketbooks. can be useful for giving precise dates regarding Jane’s daily life, but by their very nature do not give any information about her opinions or her character.

Thirdly, her novels give some biographical information, but this has to be

identified in conjunction with reading her letters. For example, we know from her letters that she did not visit Northamptonshire before writing Mansfield Park, but relied upon Henry to provide her with local information, and we know that it was her visit to Lyme Regis which gave her the background for chapters 11 and 12 in Persuasion.

So fourthly and finally, we are left with oral tradition, the dredged-up memories, most of them surfacing only many years later, of the conversations that her family and friends had with and about Jane. Such memories originate with her siblings and their children, and are based on personal knowledge; they circulated within the family between 1820-70, and were then passed on to later generations, some still as oral tradition, others in the form of memoirs and reminiscences written down in the late nineteenth or early twentieth centuries. These unique anecdotes are widely scattered in different books or manuscripts, and like pieces of a jigsaw have to be found and slotted into place before the picture is complete.

Memoir of Jane Austen, Audio from LibriVox, script written by James Edward Austen-Leigh. No reader listed.

https://archive.org/details/memoir_jane_austen_0805_librivox

Please read the book’s description in the Project Gutenberg section above.

Jane Austen’s sailor brothers: being the adventures of Sir Francis Austen … and … Charles Austen; by Hubback, J. H. (John Henry), b. 1844; Hubback, Edith C. (Edith Charlotte), 1876 – Publication date 1906, London, J. Lane, New York, J. Lane company

https://archive.org/details/janeaustenssailo00hubbrich/page/n13/mode/2up

In this book…

My daughter and I have made free use of the Letters of Jane Austen published in 1884, by the late Lord Brabourne, and wish to acknowledge with gratitude the kind permission to quote these letters, given to us by their present possessor. In a letter of 1813, she speaks of two nephews who ” amuse themselves very comfortably in the evening by netting ; they are each about a rabbit-net, and sit as deedily to it, side by side, as any two Uncle Franks could do.” In his octogenarian days Sir Francis was still much interested in this same occupation of netting, to protect his Morello cherries or currants. It was, in fact, only laid aside long after his grandsons had been taught to carry it on. – cherries or currants.

– John H. Hubback, 1905 (John was the great-nephew of Jane Austen through his wife, Catherine’s side. She was the daughter of Sir Francis William Austen, JA’s sailor brother.)

Jane Austen, A Biography, by Elizabeth Jenkins, 1949. The Universal Library, Grosset & Dunlap, NY.

https://archive.org/details/janeausten0000eliz_w9e7

This book is…

The first full-length study by someone who was not a collateral descendant of the Austens was written by Elizabeth Jenkins in 1938… Miss Jenkins was the first to properly use Chapman’s edition of the letters, and was also allowed by RAA (Richard Arthur Austen-Leigh) to see other unpublished family papers. This work was well-balanced, very readable, as accurate in its facts as was then possible, and placed Jane Austen clearly against the background of her times; it consequently remained the definitive biography for fifty years.

Georgian/Regency England

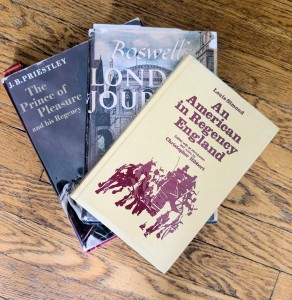

The Prince of Pleasure and His Regency 1811-20, by J.B. Priestley, 1969.

https://archive.org/details/princeofpleasure0000jbpr

Description in this book by the author…

With a pair of wild spendthrifts like Fox and Sheridan keeping him company night after night, the young Prince was not likely to imitate his father’s frugal habits. He was soon in debt and he never really got out of it. Yet for this his father, the careful George III, is at least as much to blame…The King had been unwise in first keeping his son, a full-blooded, high-spirited youth, so close to a dull and cheese-paring Court. He had been even more unwise when he had allowed the Prince of Wales his independence and his own establishment at Carlton House.- Priestly, p 24

An American in Regency England: The Journal of a Tour in 1810-1811, by Louis Simond, edited with an introduction and notes by Christopher Hibbert. The History Book Club, London 1968.

https://archive.org/details/americaninregenc0000loui

In this book:

The journal…while it adds little new to our knowledge of Regency England…deserves to be recognized as one of the most evocative portraits of Britain and the British to have been drawn by a foreigner during the years of the Napoleonic Wars. – Hibbert, Introduction

April 29–We have seen Mrs Siddons [55 yrs old)] again in the Gamester, and she was much greater than on the first day. Perfect simplicity, deep sensibility, her despair in the last scene, mute and calm, had a prodigious effect. There was not a dry eye in the house…Simond, 1810.

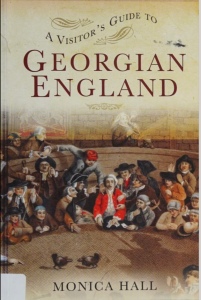

A Visitor’s Guide to Georgian England, by Monica Hall, 2017. Pen & Sword.

https://archive.org/details/visitorsguidetog0000hall/mode/2up

In this Book…

Monica Hall creatively awakens this bygone era, filling the pages with all aspects of daily life within the period, calling upon diaries, illustrations, letters, poetry, prose, 18th century laws and archives. This detailed account intimately explores the ever changing lives of those who lived through Britains imperial prowess, the birth of modern capitalism, the reverence of the industrial revolution and the upheaval of great political reform and class division. – Front description

Above all, the Georgian were optimistic risk-takers. They had to be, as there was no other way to live. They often did dangerous work in which the risk of tetanus or sepsis from wounds was ever present. The Industrial Revolution was underway, bringing both investment and employment opportunities – and the risk of losing money. Sanitation and drinking water was dubious to say the least, especially in towns and cities, and medical help were equally haphazard. Childbirth was still both inevitable and dangerous. But, most importantly, the Empire-builders were on the move. – Hall, Chapter 1, P 1.

Travel in England from pilgrim and pack-horse to light car and plane, by Thomas Burke, 1886-1945, first published 1942.

https://archive.org/details/travelinenglandf0000burk/page/n7/mode/2up

In this book: Chapters III & IV of this book are pertinent to the Georgian Era.

Chapter III: Georgian Journeys https://archive.org/details/travelinenglandf0000burk/page/94/mode/1up?q=Georgian+Journeys

In a ‘Tour Through the South of England (1791)’ Edward Daniel Clarke went with a friend…”and they took with them, as valet, the local barber–a sort of Partridge [small or insignificant man]. Travel was something new to the barber. He had never been fifty miles from his own door and every incident of the journey filled him with alarms. London frightened him, and Portsmouth with its sailors bewildered him. He had never stayed at an inn, and the hurry and confusion of a large inn almost caused a nervous breakdown. He was always bowing to the waiters, and stepping aside from them and colliding with the kitchen boys, and being kicked by one and pushed by the other, so that he was constantly running to his employer for protection. – Georgian Journeys, Ch 3, p 82.

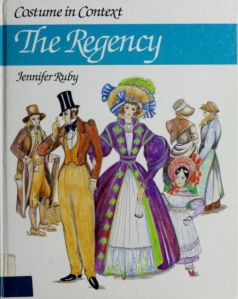

Costumes in Context: The Regency, by Jennifer Ruby, 1989

https://archive.org/details/regencycostumein00jenn/page/n3/mode/2up

This book…

…Traces the major fashion developments of the period, comparing the clothing of the well-to-do with that of less fortunate classes…

Each book in this series is built round a fictitious family. By following the various members, sometimes over several generations…you will be able to see the major fashion developments of the period and compare the clothing and lifestyles of people from all walks of life…

Major social changes are mentioned in each period and you will see how clothing is adapted as people’s needs and attitudes change…

Many of the drawings in [this] book have been taken from contemporary paintings.

This is another take on fashions during the regency era on IA:

Costume Reference 5: The Regency, by Marion Sichel, 1977.

https://archive.org/details/regencycostumere00mari/mode/2up

This book has better drawings and sketches, but does not include costumes year by year that represent all the classes.