Inquiring Readers: I will be contributing four posts to Pride and Prejudice Without Zombies, Austenprose’s main event for June/July – or an in-depth reading of Pride and Prejudice. This post discusses the clothes that the characters would have worn in relation to the film adaptations and actual fashion plates of the time. Warning: this is a long post.

The Netherfield Ball. Ah! How much of Jane Austen’s plot for Pride and Prejudice was put on show in this chapter! Elizabeth Bennet – its star – enters the ball room hoping for a glimpse of a strangely absent Mr. Wickham, but is forced to dance two dances with bumblefooted Mr. Collins, whose presence she somehow can’t seem to shake. (From his actions the astute reader comes to understand that this irritating man will be proposing soon.)

Mr. Darcy then solicits Lizzie for a dance, and his aloofness and awkward silences during their set confirms in Lizzie’s mind that he suffers from a superiority complex.

As the evening progresses her family’s behavior is so appalling (Mary hogs the pianoforte with her awful playing; Kitty and Lydia are boisterously flirtatious with the militia men; and Mrs. Bennet brazenly proclaims to all within earshot that Mr. Bingley and Jane are as good as engaged) that the only enjoyment Lizzie takes away from the event is in the knowledge that Mr. Bingley is as besotted with Jane as she is with him.

Jane and Bingley have eyes only for each other, while Lizzie cannot wait for her set with Mr. Collins to end, Pride & Prejudice 2005

In anticipation of furthering her acquaintance with Mr. Wickham, Lizzie dressed with extreme care, making sure both her dress and hair looked perfect. In the image below, Jennifer Ehle’s “wig” is adorned with silk flower accessories, and a string of pearls, which was the fashion of the time. She wears a simple garnet cross at her throat (Jane Austen owned one made of topaz) and her dress shows off her figure to perfection.

Jane Austen wrote Pride and Prejudice between 1797 and 1813, when the novel was accepted for publication. For continuity’s sake, I will discuss the style of dresses worn from 1811-1813.

Pride and Prejudice 1980 and 1995 stayed fairly consistent in using costumes that were based on fashions from the early 19th century. Pride and Prejudice 2005 took great liberties in several ways, and I shall point out the most egregious deviations or obvious errors as they arise.

For a private ball, Lizzie and Jane would don their best ball gowns, also known as full dress gowns. They would have worn simpler dresses for a public assembly hall dance, such as the one in Meryton when Mr. Bingley and Mr. Darcy made their first appearance, and where anyone in town who could afford the price of a season ticket could attend. (This is one of the reasons that the Bingley sisters and Mr. Darcy did not comingle with the hoi poloi! Imagine Mr. Darcy dancing with an apothecary’s daughter!) The image above shows Lizzie in a dark green cotton gown and Charlotte in a brown dress. None of the ladies are wearing hair ornaments or gloves, nor holding fans.

For a private ball, in which the guest list could be controlled by the host, the guests went all out to show off their finery. Their best gowns were retrieved from storage and were accessorized with long gloves, fancy hair ornaments, a fan, dance card, delicate necklaces and earrings, and a beautiful Norwich or India shawl. The dresses were made of finer muslin or silk (an extremely expensive fabric worn largely by the rich). They had these qualities in common: bare necks and/or low necklines, short puffy sleeves, and long, columnar skirts embellished with lace, embroidery or ribbon. Under the dresses, the ladies wore bodiced petticoats and silk stockings and slippers. By 1813, trains on full dress gowns were beginning to go out of fashion or were reduced considerably in length, except for court gowns, which followed a different set of rules.

Balls were generally scheduled during a full moon so that carriages traveling over dark roads were guided by lunar light. As the revelers approached the house, brightly lit lanterns dangling from trees or torches planted alongside the road would light the way; and the rooms themselves would be emblazoned from the light of hundreds of beeswax candles, which tended not to drip and would give off a steady flame (but were horrifically expensive). Candlelight made large rooms look smaller, since so many dark corners remained unlit. The resulting low light was kind to aging skin and the badly complected.

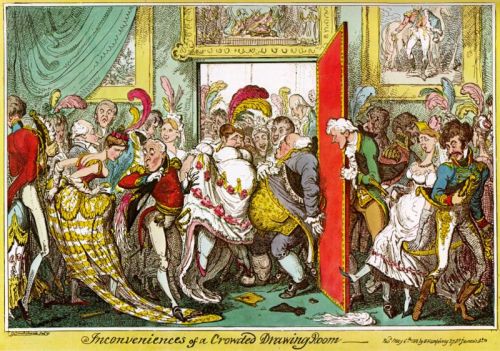

The hundreds of blazing candles emitted no more light than that of a few 25 watt bulbs. The light was enhanced by the crystal pendants that acted as reflectors and by mirrors, that were often placed in back of wall sconces. Candlelit rooms became hot over time and ceilings were covered in soot from the smoke. With the number of people assembled in one space and the great number of burning candles, ball rooms required good ventilation. Most women carried fans. One can imagine how hot the men must have felt wearing long sleeved shirts and waistcoats under coats and cravats that covered the neck up to the chin. As an aside, if an overabundance of guest spilled over from room to room, the event was deemed to be a “crush,” (or a rousing success).

One can suppose that the gathering at Netherfield was a more sedate affair than the one depicted above by Cruikshank, with only the cream of Meryton crop invited to partake in the festivities. Given the size of Netherfield Park, a crush would have looked more like this:

The golden glow emanating from chandeliers and wall sconces would alter the color of the gowns that the ladies wore. Colors that looked good in the yellow light would be chosen for greatest effect, colors that clashed would be avoided. I imagine that a blue gown could look green under yellow light, and that a strong puce could look black or that lavender would turn a sickly gray.

Young ladies of fashion preferred to wear white during the Regency era, but they would also wear soft pastel colors, as shown in the image below from P & P 1995. Notice the slight differences in the necklines and details of sashes and embellishments, but the gowns look as if they were designed for the same era.

A Lady of Distinction, author of The Mirror of Graces (1811), advised young maidens how to dress:

In the spring of youth, when all is lovely and gay, then, as the soft green, sparkling in freshness, bedecks the earth; so, light and transparent robes, of tender colours, should adorn the limbs of the young beauty…Her summer evening dress may be of a gossamer texture; but it must still preserve the same simplicity, though its gracefully-diverging folds may fall like the mantle of Juno…In this dress, her arms, and part of her neck and bosom may be unveiled: but only part. The eye of maternal decorum should draw the virgin zone to the limit where modesty would bid it rest.”

A Lady of Distinction advised married ladies like Mrs. Bennet to make more modest choices:

As the lovely of my sex advance towards the vale of years, I counsel them to assume a graver habit and a less vivacious air…At this period she lays aside the flowers of youth, and arrays herself in the majesty of sobriety, or in the grandeur of simple magnificence…Long is the reign of this commanding epoch of a woman’s age; for from thirty to fifty she may most respectably maintain her station on this throne of matron excellence.”

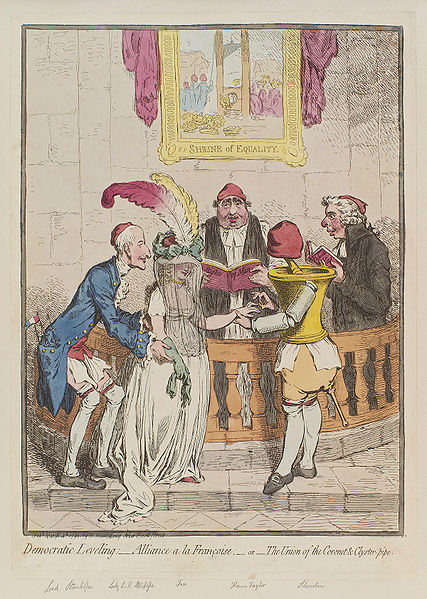

Mrs. Bennet and other matrons are shown covering their hair with feathers or caps. At their age, they were allowed to wear deeper but more somber colors. If they chose to wear white, they were advised to add a striking color through accessories, such as a richly colored shawl. The costumes in Pride and Prejudice 2005 combine the fashionable dress of 1812-1813 (women at left below) with old-fashioned 18th century gowns that had natural waists (Brenda Blethyn and woman at right). Since Regency gowns kept their “value” longer, it makes sense that matrons would wear them beyond their fashionable hey day. It would not make sense for a young lady on the marriage mart to wear anything but the most up to date gown she could afford.

All five Bennet girls were “out,” much to Lady Catherine de Bourgh’s surprise, and allowed to attend balls and parties en masse. This meant that all the girls would need their own party and ball dresses in addition to their regular gowns, a quite expensive proposition for Mr. Bennet, who, one suspects, would have preferred to spend his money on books . Handmade fabrics were still very costly before the age of mass production and ladies recycled their gowns as a matter of course. It was the tradition to remake their gowns, or to hand them down to younger or smaller members of the family to be recut in the latest fashion or refurbished with new trim and accessories, which were more affordable.

Silks were quite expensive. Mr. Bennet could probably afford to dress Jane in silks since she was the eldest daughter and her dresses could be handed down to the younger girls, but the cost would be too prohibitive for him to outfit all his daughters in such a costly fabric.

The Bennet girls lived less than a day’s drive from Town and received the most recent fashion magazines within days of their city counterparts, but they did not have access to the latest textiles at the fabric warehouses in London. Whenever friends or relatives visited London, they came armed with orders to purchase fabrics and clothing items at the Draper’s.

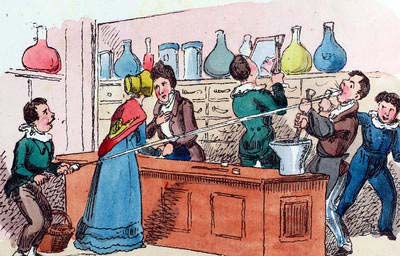

Traveling salesmen and local shops could offer only a limited supply of fabrics to choose from, and one imagines that quite a few ladies in a small community would be forced to make dresses (or have them made up by a dressmaker) from the same bolt of cloth. Local drapers, dressmaker shops, and millinary shops would have looked much like the shop below:

In 1828 the proprietor of this milinary shop in Sutton Valence, Miss Elizabeth Hayes, "went to London to purchase Bonnetts at Ludgate Hill".

Because fashion took longer to take hold in the “provinces”, most of the women in Meryton would have worn dresses that were popular several years back (1811 or 1812). They could update their gown with lace and ribbon, or embroidery, and make minor adjustments, which is what Jane Austen often wrote about in her letter to Cassandra. In that way they updated their gowns and introduced variety.

Miss Bingley and Mrs. Hurst, on the other hand, would be decked out in the latest and most elaborate finery that London fashion had to offer. The fabrics and trims on Miss Bingley’s gown are rich and costly and is made up of a color that was quite in vogue. Mrs. Hurst’s hairdo, which evokes a Roman matron, must have taken a while to fashion. Her decolete is more obvious; not only is she better endowed than her sister, but her neckline is lower and the sleeves are puffier. She, too, wears a more elaborate necklace than the Bennet girls, but is is matched with a simple pair of pearl drop earrings. Compare Mrs. Hurst’s hairstyle to that of the ancient Roman portrait below.

Pride and Prejudice 2005 shows most of the young women wearing pretty but simple muslin ball gowns, many of which would be embroidered in whitework. The young ladies of that era were adept seamstresses, and they learned to embroider at a young age. Whitework embroidery patterns were readily available in fashion magazines.

Lizzie’s hair (below) is styled becomingly with pearls, but it has a more modern, contemporary flavor than Miss Bingley’s and Mrs. Hursts hairdos in the (3rd) image above.

Caroline Bingley (below) looks like she’s dressed for a 2005 wedding. There is nothing Regency about her outfit or her hair. While actress Kelly Riley looks beautiful, I wince every time I see her in this supposed Regency costume.

Director Joe Wright wanted to play up Lizzie’s tomboyish side, but regardless of her affinity for plein air walks she would still have followed propriety and worn gloves. Her dress, too, has a modern feel. We know that Keira Knightely has a small bosom, but a corseted petticoat would have given this gown more structure. In addition, her waist is a tad too low. Compare this image with the one above, and you get virtually no sense of place or time in Pride and Prejudice 2005 via the gowns.

Elizabeth dancing with bare arms. Her hair is elaborately fashioned, but the gown's waist should be a little higher.

In the 1980 movie adaptation, Lizzie is shown wearing a more elaborate ballgown. She is also holding a fan, a handy instrument in a crowded and hot ballroom! My biggest complaint with her gown is that her bosom is showing entirely too much, and would have earned disapprobation from A Lady of Distinction.

Ornaments were woven through upswept hairdos. Small tight curls framed the face and tumbled in front of ears. The only ornamentation in Charlotte’s hair (image above) are thin braids that are twisted in such a way as to decorate the upswept “do.”

One note about the opera gloves used in these film adaptations. They should be worn over the elbow and they should be quite loose! In the image at right, below, the loose long gloves fall naturally below the elbow.

Up to now I’ve shown the fashions from movie adaptations. But the fashion plates from the Regency era are even more revealing. Let’s look at some sample plates from 1811 to 1813. Note that throughout these three years, the waists remained high, just under the bosom. Gown lengths seemed to vary, but the hems would creep up as the decade progressed to reveal neat ankles and lovely slippered feet. In 1811, such brazenness was frowned upon by A Lady of Distinction.

It is apparent from the above illustration that the bodice petticoat provided a “shelf” silhouette to the bosom. A Lady of Distinction found this new fashion abhorrent:

The bosom, which nature has formed with exquisite symmetry in itself … has been transformed into a shape, and transplanted to a place, which deprives it of its original beauty and harmony with the rest of the person. This hideous metamorphose has been effected by mean of invented stays or corsets…”

Jane Austen noted in one of her letters to Cassandra how long sleeves were becoming fashionable for evening. I imagine this dress was meant to be worn on a cold night, for such sleeves would have been stifling in summer. The sleeves are known as Mamaluke or Marie Sleeves.

In the illustration above, you can best see how the loose gloves bunched below the elbows. This dress comes with a short train, ribbon embellishments at the hem, and white lace ruffles around the neckline and on the sleeves. Pearls and flowers are woven throughout the hair.

Let’s not forget the gentlemen. Their attire included beautifully formed jackets and waistcoats, white pantaloons, silk stockings, leather slippers, and short gloves. Their cravats, it goes without saying, were tied with precision and made with the whitest starched linen. A cravat pin, a quizzing glass, snuff box, and fob watch completed their sartorial splendor.

More on the topic:

- Pride and Prejudice 1995, Lizzie and Darcy dance to Mr. Beveridge’s Maggot

- Designing the costumes for P&P 1995

- Public Reaction to Rising Waists in the 18th Century

- Regency Dress Database

- Fashions During Cassandra Austen’s Lifetime

This post is copyrighted. You may link to it, and use excerpts with attribution, but you may not place it wholesale on your blog. Always, always attribute this post or material derived from it to Vic at Jane Austen’s World.