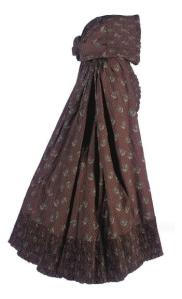

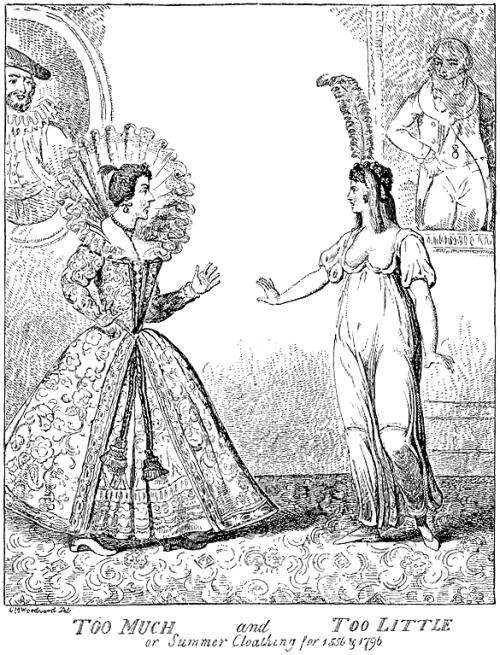

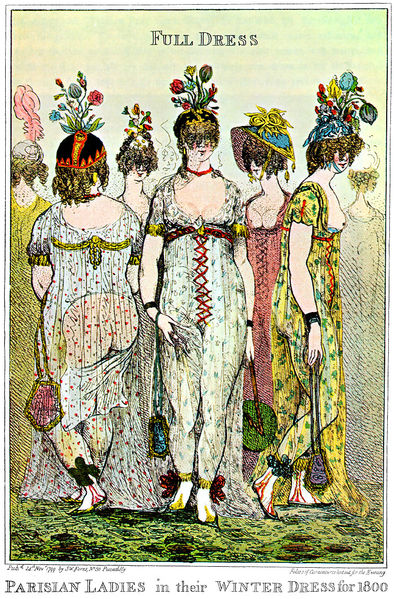

We’ve all come to associate Regency women’s fashion with delicate white muslin fabrics – sprigged muslin, spotted muslin, checked and striped muslin, and embroidered muslin. Henry Tilney, the hero in Northanger Abbey, was well-acquainted with muslins through his sister, who wore only white.

Sheer white muslin gown with whitework embroidery. Image @Vintage Textile

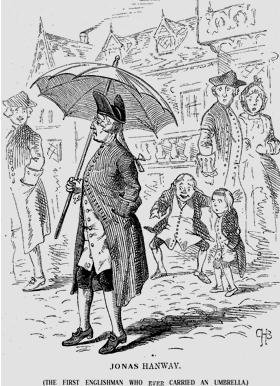

In the 17th century and until the late 18th century, England imported muslin, a thin cotton material, from India. The British East India Company traded in Indian cotton, silk fabrics, and Dacca (Dhaka or modern-day Bangladesh) muslins. Muslins from Bengal, Bihar and Orissa were also imported. The delicate cloth, which first originated in the Middle East in the 9th century, was perfect for clothing and curtains in hot, arid countries. – Muslin: Encyclopedia Britannica

Muslin gown, 1816

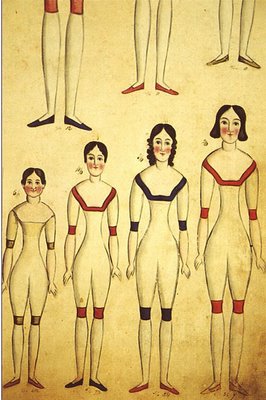

Muslin was a finely woven light cotton fabric in plain weave without a pattern, and had identical warp and weft threads. The fabric selection is quite flexible, coming in a wide variety of weights and widths. It accepts dyes and paints so successfully that today it is often used for theatrical backdrops and photographic portraits. One observation must be made: muslins of the past were made of much finer, more delicate weave than today’s muslins. – How Is Muslin Fabric Made?

Buttons on a modern muslin fabric

Muslin gown circa 1815, Bath museum

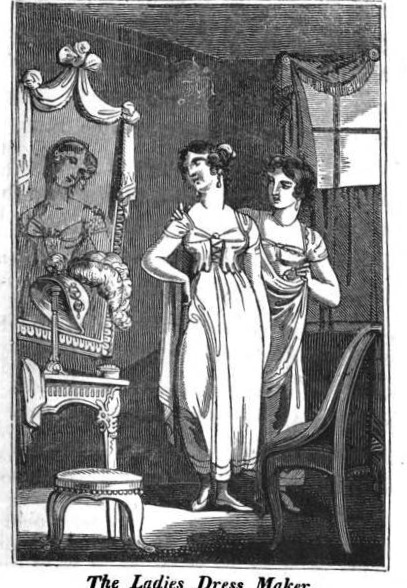

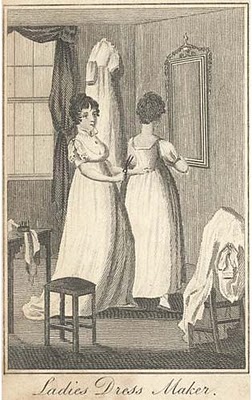

An important feature of muslin fabrics is its ability to drape. Regency fashions were based on robes and garments from antiquity. The ability to drape and maneuver the fabric on the figure was an important feature of this cloth. Today, designers use muslin as a test garment for cutting and draping a design before creating the final dress from more expensive fabrics.

Another excellent feature of muslin is its ability to take dye, paints, and embroidery. The cloth accepted many patterns, motifs and designs that made it versatile and unique. – Textile as Art

Plus the white fabric was a mark of gentility. White was difficult to keep clean or required constant cleaning. It was one thing for an aristocratic lady like Eleanor Tilney to wear white, but another for a maid to presume to wear such a high maintenance garment. Mrs Norris, that awful woman from Mansfield Park, approved of Mrs. Rushworth’s housekeeper’s action of turning away two housemaids for wearing white gowns.

Muslin evening dress. Image @Metropolitan Museum of Art

Embroidery transformed the simple white muslin gown into works of art. Whitework embroidery was particularly striking, but colored threads could be equally beautiful. The draping quality of the cloth lent itself well to columnar-shaped empire waist gowns.

Indian sprigged muslin gown, 1800. Image@Kelly Taylor Auctions Trouvais

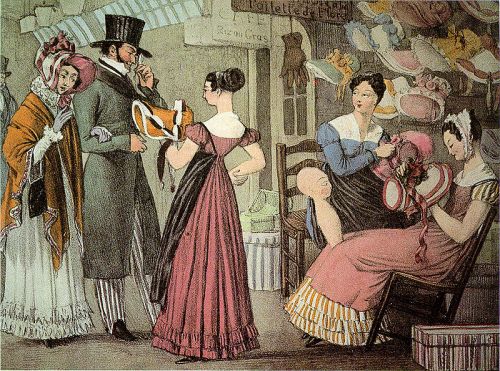

Muslin was imported from the Far East for centuries. Then the weavers in west Scotland, who were proficient in spinning fine cottons such as linen, cambric, and lawn, began to pay attention to weaving a finer, more delicate cloth.

Sheer muslin gown, 1800. Image @Victoria & Albert Museum

Muslins, therefore (plain for the most part in Glasgow, and fancy ornamented in Paisley),were among the earliest and principal cotton fabrics produced on the looms of the west of Scotland. About the year 1780 James Monteith, the father of Henry Monteith, the founder of the great printworks at Barrowfield, and of the spinning and weaving mills at Blantyre, warped a muslin web, the first attempted in Scotland; and he set himself resolutely to try to imitate or excel the famous products of Dacca and other Indian muslin-producing centres. As the yarn which could then be produced was not fine enough for his purposes, he procured a quantity of “bird-nest” Indian yarn, “and employed James Dalziel to weave a 6-4th 12” book with a handshuttle, for which he paid him 2Id. per ell for weaving;. It is worthy of remark that the same kind of web is now wrought at 2|d. per ell The second web was wove with a-fly shuttle, which was the second used in Scotland. The Indian yarn was so difficult to wind that Christian Gray, wife of Robert Dougall, bellman, got 6s. 0 J. for winding each pound of it. When the web was finished Mr Monteith ordered a dress of it to be embroidered with gold, which had presented to Her Majesty Queen Charlotte.”1

1817 Muslin day dress. Image @Bowes Museum

Once fairly established, the muslin trade and various other cotton manufactures developed with extraordinary rapidity, and diverged into a great variety of products which were disposed of through equally numerous channels. Among the earliest staples, along with plain book muslins, came mulls, jacconets or nainsooks, and checked and striped muslins. Ginghams and pullicats formed an early and very important trade with the West Indian market, as well as for home consumption. These articles for a long period afforded the chief employment to the hand-loom weavers in the numerous villages around Glasgow and throughout the west of Scotland. The weaving of sprigged or spotted muslins and lappets was subsequently introduced, the latter not having been commenced till 1814. Although the weaving of ordinary grey calico for bleaching or printing purposes has always held .and still retains an important place among Glasgow cotton manufactures, it has never been a peculiar feature of the cotton industry; and the very extensive bleaching and print-works of the locality have always been supplied with a proportion of their material from the great cotton manufacturing districts of Lancashire. – p 501, The Encyclopaedia Britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, and general literature, Volume 6, Thomas Spencer Bayne, 1888.

Embroidered muslin round gown, 1795. Image @Cathy Decker

More on the topic:

Read Full Post »