Inquiring readers: Once upon a time, road travel was fraught with danger and a traveler could be held up by a highwayman at any time. Jerry Abershawe was such a man. Tony Grant (London Calling) writes about him in this post.

Not far from where I live, on the edge of Wimbledon Common where the Kingston Road passes, are some trees on the side of a small rise of ground. This part of the common is called Jerry’s Hill. It is named after the 18th-century highwayman called Jerry Abershawe, who frequented those parts and held up carriages on their way between Kingston and London. He was one of the last highwaymen.

A highwayman was a thief who held up passers by, usually people travelling in carriages, at gun point or blunderbuss point, and relieved the passengers of their valuables. Some attacks on coaches were brutal and people were killed. Highwaymen weren’t all the dashing handsome masked desperados of fiction with the manners of a lord and a twinkle in the eye for a beautiful lady. “Stand and deliver!” was their traditional call. They chose lonely remote stretches of the highways to perform their dastardly deeds, but they also had to be sure they chose an area where there was regular traffic going to and fro or their despicable mission would be pointless. They chose places just outside towns and cities where there was a constant flow of people travelling. Wimbledon, then a small rural village on the outskirts of London and with a vast area of wild untamed common land around it, was an ideal spot.

Jane Austen was travelling to London from Steventon in 1796 the year after Jerry Abershawe was executed. They were about the same age, 20 and 22 years old.

To Cassandra Austen Thursday 15 – Friday 16th September:

“….As to the mode of our travelling to Town, I want to go in a Stage Coach, but Frank will not let me. As You are likely to have the Williams’ & Lloyds with You next week, You would hardly find room for us then-. If anybody wants anything in Town, they must send their Commissions to Frank, as I shall merely pass thro’ it- The Tallow Chandler is Penlington, at the Crown & Beehive Charles Street, Covent garden.”

Travelling from Steventon, Jane would not have gone through Kingston upon Thames and the London Road leading out of Kingston where Jerry Abershawe plied his highwayman trade. However, you can understand Frank’s concerns for Jane using the stagecoach. A stagecoach carrying a variety of passengers, some undoubtedly wealthy, would have been a target for a highwayman.

From Steventon, the most direct route to London would have taken her through Basingstoke, Virginia Water, Staines, Richmond upon Thames, Hammersmith and on to Westminster and the centre of London. From Staines she would have been travelling on what was known as The Great West Road which lead directly to the second most important city after London, in Georgian times, Bristol, the centre of the slave trade. Some very wealthy merchants and members of the aristocracy would have travelled this road. It must have had its fair share of highway robbers. Stagecoaches on this road would most certainly have been prime targets. So Frank was right to refuse Jane her wish. But maybe the excitement and the risk appealed to Jane. She was young after all. It does not say in Jane’s letter how they did get to Town, but I presume it was in less conspicuous transport and with her brother.

In 1813, Jane did travel along the London Road leading out of Kingston, Jerry Abershawe’s haunt. She did this many times from Chawton. There is no hint in her letters of any possible dangers but by the time she was living in Chawton, although the Kingston route was now her most direct route to Town, highwaymen were all but extinct. The toll roads had made highway robbery very difficult. Roads were manned every few miles and the people on them had paid to use them. This made it very difficult for highway robbers to make their escape along these routes so this crime virtually died out.

To Cassandra Austen Wednesday 15 – Thursday 16 September 1813 Henrietta Street (1/2 past 8-)

Here I am, my dearest Cassandra, seated in the Breakfast, Dining, sitting room, beginning with all my might. Fanny will join me as soon as she is dressed & begin her Letter. We had a very good journey- Weather & Roads excellent – the three first stages for 1s – 6d & our only misadventure the being delayed about a quarter of an hour at Kingston for Horses, & being obliged to put up with a pr belonging to a Hackney Coach & their Coachman, which left no room on the Barouche Box for Lizzy, who was to have gone her last stage there as she did the first;- consequently we were all four within , which was a little crowd;-We arrived at quarter past 4 …”

This time there was no sense of Jane’s brothers putting their foot down and refusing this time to let her travel in what appeared to them in the past in an inappropriate mode of transport. The party Jane travelled with appeared to be Henry, Lizzy and Fanny. There was no sense of danger, just the excitement of the journey, and from Kingston on their last stage, the cramped conditions of four of them inside the barouche. (Imagine being squashed inside a barouche with Jane Austen. What a thought.)

The women would have passed the inn at the bottom of Kingston Hill, where Jerry Abershawe made his headquarters, before their barouche made the long rising trek up the hill onto Wimbledon Common, going past Jerry’s Hill, where I am sure the gibbet would still have been displayed on the right hand side of the road. There probably was no sign of the remains of Jerry Abershawe by that time though. His body had been pecked clean by the crows and his bones had been taken as souvenirs. His finger bones and toes bones were used in candleholders. Jerry Abershawe was the last person to have his body displayed like this on a gibbet.

Louis Jeremiah Abershawe(1773-3 August 1795), better known as Jerry Abershawe, terrorised travellers between London and Portsmouth in the later 18th century. He was born in Kingston upon Thames and at the age of 17 began his life of crime. He formed a gang, which was based at an inn on the London Road between Kingston and Wimbledon, at the bottom of Kingston Hill called the Bald Faced Stag. I am sure, as well as his primary occupation of highway robbery, Jerry Abershawe also managed to gain the odd carcase of a King’s deer from Richmond Park, which backed on to the Bald Face Stag Inn. The inn no longer exists, but there was a very large and comfortable pub and restaurant built there in the early 1900’s that, just a few years ago, was demolished for new housing built on the site.

Jerry had other places of refuge at Clerkenwell near Saffron Hill. He used a house called the Old House in West Street. Other highwaymen also used this house. Jack Sheppard and Jonathan Wild were known to have stayed there. It was a house renowned for its dark closets, trap doors, and sliding panels.

All attempts to bring Jerry Abershawe to justice failed until in January 1795, when he shot dead one of the constables sent to arrest him in Southwark and badly injured the other constable sent along too. Abershawe was arrested at a pub in Southwark called The Three Brewers. He was brought to trial at Surrey Assizes in July of 1795, and convicted and sentenced to death. On Monday 3 August 1795, Jerry Abershawe was hung on Kennington Common, a couple of miles from Wimbledon and then his body was set up on a gibbet on the hill overlooking the Kingston Road, which was more commonly known then as the London Road, next to Wimbledon Common near the scene of many of his highway robberies. It remained there for all passers by to see and be warned about the price to pay for evil ways.

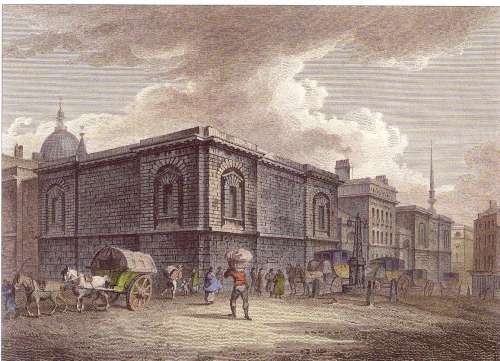

The Newgate Calendar for 1795 describes the manner of his being found guilty of murder. Newgate prison was a notorious London prison in which criminals waiting for trail would be held, and it was there that Jerry Abershawe was incarcerated before his execution.

When the judge appeared in his black cap, the emblem assumed at the time of passing sentence on convicted felons, Abershaw, with the most unbridled insolence and bravado, clapped his hat upon his head, and pulled up his breeches with a vulgar swagger; and during the whole of the ceremony, which deeply effected all present except the senseless object himself, he stared full into the face of the judge with a malicious sneer and affected contempt, and continued this conduct till he was taken, bound hand and foot from the dock, venting curses and insults on the judge and jury for having consigned him to, “murder.”

The Newgate Calendar also describes his execution on Kennington Common.

He was executed on Kennington Common, on the 3rd of August, 1795 in the presence of an immense multitude of spectators, among whom he recognised many acquaintances and confederates, to whom he bowed, nodded, and laughed with the most unfeeling indifference. He had a flower in his mouth, and his waistcoat and shin were unbuttoned, leaving his bosom open in the true style of vulgar gaiety; and talking to the mob, and venting curses on the officers, he died, as he had lived, a ruffian and a brute!”

Highwaymen especially were supposed to affect an attitude and a jocular type of behaviour called gallows humour. It seems that Jerry Abershawe went to his death displaying ribald and stentorious gallows humour.

At least Jane was now safe on her journeys to London. But I wonder if she had just a small wish for the thrill of danger and would have loved to encounter Jerry on the wild wilderness of Wimbledon Common and ,”stand and deliver,” to him. If it had happened, would her novels have turned out differently in some ways?

Jane was 20 years old when Jerry died at the age of 22. Just maybe Jane would have loved the thrill of adventure on a journey with the threat of Jerry Abershawe round the next bend.

Post script:

After writing this article I just couldn’t get a nagging thought out of my head.

Why and how did Jerry end up as a highway robber?

I know he was young, 22 years of age when he was caught and executed. There is no mention of family or wife or children or any sort of familial attachments. I can imagine him being brought up, an orphan, perhaps on the market streets of Kingston having to survive and live by his wits. It doesn’t take much to imagine the step into criminality to survive. He got in with the wrong lot obviously. An intelligent, bitter, hard done by, street wise kid gone wrong and obviously with a big personality. We can compare him with those who go off the tracks in our own society today. The forces for evil don’t change apparently. Obviously this is a total surmise but I feel better for it.