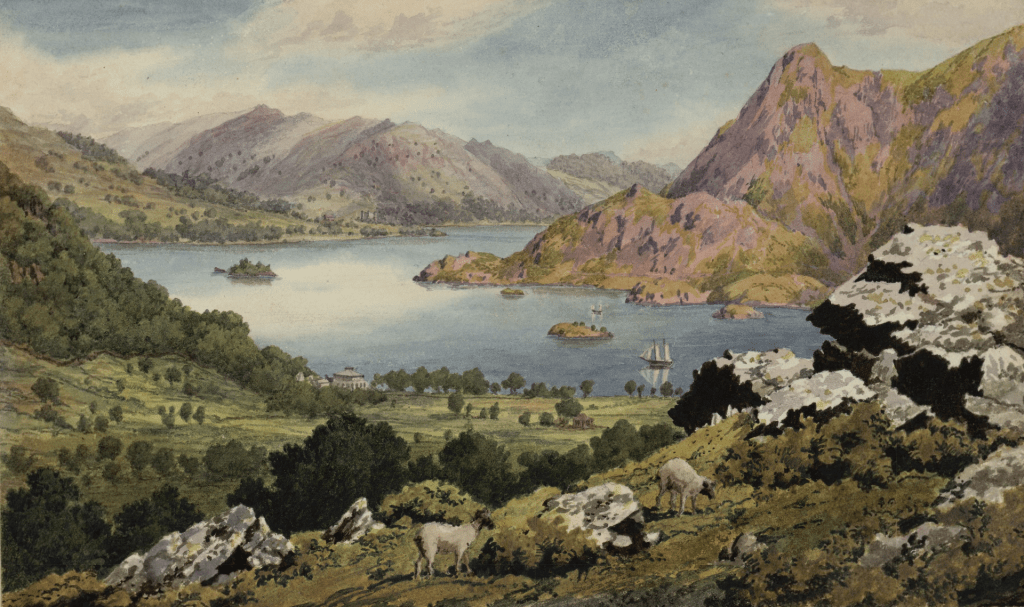

This is the time of year when I start to dream of traveling to England or other beautiful places over the summer. I know just how Elizabeth Bennet felt when looking forward to her trip with her Uncle and Aunt Gardiner.

What a delightful thought! Anticipation is half the joy of any exciting pursuit. Her words could not be more true:

Her tour to the Lakes was now the object of her happiest thoughts: it was her best consolation for all the uncomfortable hours which the discontentedness of her mother and Kitty made inevitable; and could she have included Jane in the scheme, every part of it would have been perfect.

“But it is fortunate,” thought she, “that I have something to wish for. Were the whole arrangement complete, my disappointment would be certain. But here, by carrying with me one ceaseless source of regret in my sister’s absence, I may reasonably hope to have all my expectations of pleasure realized. A scheme of which every part promises delight can never be successful; and general disappointment is only warded off by the defence of some little peculiar vexation.”

Travel Plans

Like many of us who have had our plans amended, Elizabeth has high expectations of all they might see on their trip, but eventually she finds contentment in the final plans to visit Derbyshire and the Peak District but not venture to the Lakes:

…they were obliged to give up the Lakes, and substitute a more contracted tour; and, according to the present plan, were to go no farther northward than Derbyshire. In that county there was enough to be seen to occupy the chief of their three weeks; and to Mrs. Gardiner it had a peculiarly strong attraction. The town where she had formerly passed some years of her life, and where they were now to spend a few days, was probably as great an object of her curiosity as all the celebrated beauties of Matlock, Chatsworth, Dovedale, or the Peak.

Most of us can relate to Elizabeth’s feelings on the topic:

Elizabeth was excessively disappointed: she had set her heart on seeing the Lakes; and still thought there might have been time enough. But it was her business to be satisfied—and certainly her temper to be happy; and all was soon right again.

Travel Route

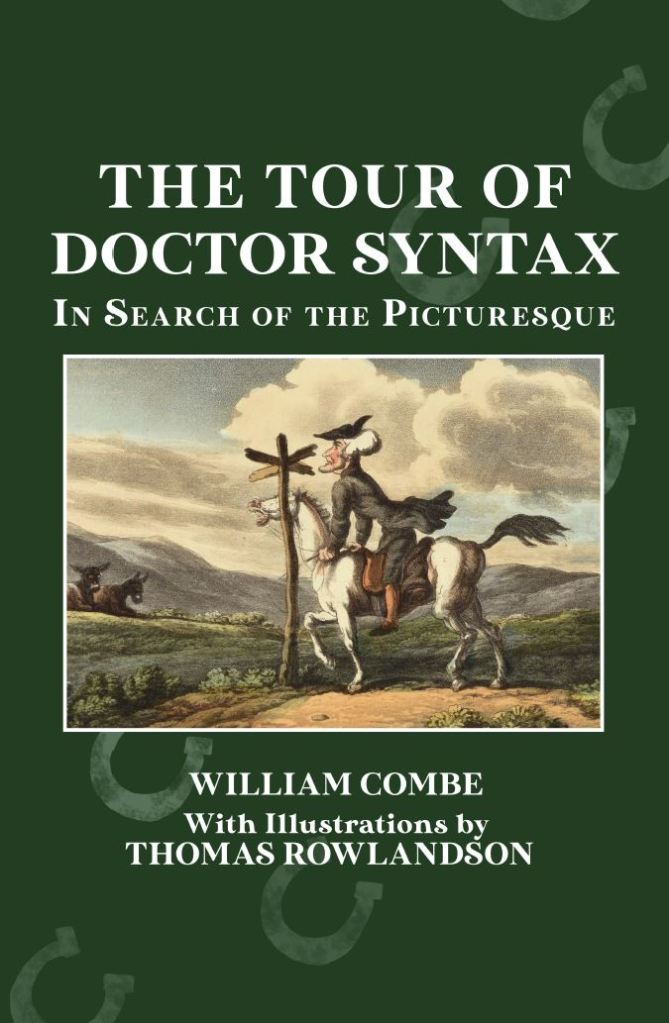

Her trip was revised, but there was still much for her to see. I’ve always been intrigued by this paragraph that tells us about the route they took on their way to Derbyshire, for there would have been many interesting sights along the way:

It is not the object of this work to give a description of Derbyshire, nor of any of the remarkable places through which their route thither lay—Oxford, Blenheim, Warwick, Kenilworth, Birmingham, etc., are sufficiently known. A small part of Derbyshire is all the present concern.

If Elizabeth and the Gardiners stopped along the way, what might these locations have looked like at the time? Most scholars agree that this trip would have taken several days, which means they would have had to change horses several times and stop for food and rest and lodging. It’s fun to imagine what all they saw and where they stopped, though we know they would have wanted as much time as possible in Derbyshire.

For anyone curious about how far and how fast people could travel in Jane Austen’s England, I highly recommend Wade H. Mann’s article, “Distance and Time in Regency England” on Quills & Quartos. It breaks down the realities of journeying by carriage, horseback, and foot, giving a clear sense of the distances and travel times that shaped the world Austen’s characters inhabited.

Oxford

Austen’s contemporary readers would have recognized Oxford as a center of learning and culture. High Street and Cornmarket Street bustled with shops, inns, and markets. The architecture would have also been of interest. There are many gardens and parks to explore and walk, museums and libraries, and several religious sites. There would have been much for Elizabeth and the Gardiners to experience along the way.

Blenheim

Blenheim Palace, the seat of the Dukes of Marlborough (which would later become the birthplace of Winston Churchill), was also on the route. As we see later when Elizabeth and the Gardiners visit Pemberley, by the late 18th and early 19th centuries, many famous estates in England had become informal tourist attractions. Wealthy travelers, and even respectable middle-class visitors, often toured grand houses while traveling through the countryside.

Warwick

Today, Warwick is a lovely little village, and the castle is one of my favorite sites to visit. During Austen’s time, Warwick Castle would have boasted recent new landscaping by Lancelot “Capability” Brown (1716–1783). Warwick Castle’s grounds were redesigned in the 18th century, and Brown’s landscapes created sweeping lawns, gentle vistas, and picturesque trees. Visitors like Elizabeth Bennet might have enjoyed exploring the grounds.

Canaletto. Warwick Castle, the East Front from the Courtyard. Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Wikimedia Commons.

Kenilworth

Kenilworth Castle, already a famous historic ruin during the Regency Era, offered visitors sweeping views, crumbling walls, and picturesque gardens. Tourists like Elizabeth Bennet might have strolled the grounds and enjoyed the romantic, dramatic scenery that made it a highlight of Warwickshire travel.

Finally, in Austen’s day, Birmingham was a bustling market and industrial town rather than a landscaped estate. Travelers might stop for lodging, shopping, or supplies, experiencing the commerce of an emerging urban center instead of picturesque grounds or aristocratic architecture.

Derbyshire

Once they arrive in Derbyshire, we know whom Elizabeth and the Gardiners visit and what they see. Unlike Elizabeth Bennet, most of us will never enjoy living at such a glorious estate as Pemberley. But we can visit many of the real, historic sites. And if we’re very lucky, perhaps we might be invited to visit a historic estate or home one day, such as my visit to Sherbourne Park.

Most of all, Elizabeth’s travels remind us that the journey is often just as important and interesting as the destination. Unless, of course, Mr. Darcy is waiting at one of those destinations.

Tune in for more about Elizabeth’s travels in the coming months!

Rachel Dodge teaches writing classes, speaks at libraries, teas, and conferences, and writes for Jane Austen’s World blog. She is the bestselling, award-winning author of The Anne of Green Gables Devotional, The Little Women Devotional, The Secret Garden Devotional, and Praying with Jane: 31 Days Through the Prayers of Jane Austen. She has narrated numerous book titles, including the Praying with Jane Audiobook with actress Amanda Root. A true kindred spirit at heart, Rachel loves books, bonnets, and ballgowns. Visit her online at www.RachelDodge.com.