by Brenda S. Cox

“There must have been many precious hours of silence during which the pen was busy at the little mahogany writing-desk, (This mahogany desk, which has done good service to the public, is now in the possession of my sister, Miss Austen) while Fanny Price, or Emma Woodhouse, or Anne Elliott was growing into beauty and interest.”–A Memoir of Jane Austen by James Edward Austen-Leigh, her nephew

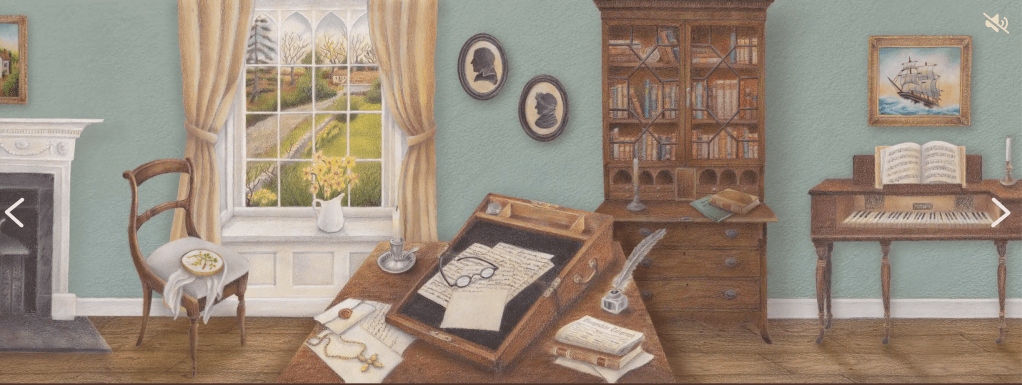

Wouldn’t you love to explore Jane Austen’s desk and room? Inger Brodey, Sarah Walton, and their amazing team at the Jane Austen Collaborative are recreating Jane’s desk and room for us to visit virtually.

While the website is still a beta version, I found lots of great information there. The plan is for it to become a “portal” linking to many Austen resources.

Jane Austen’s Desk

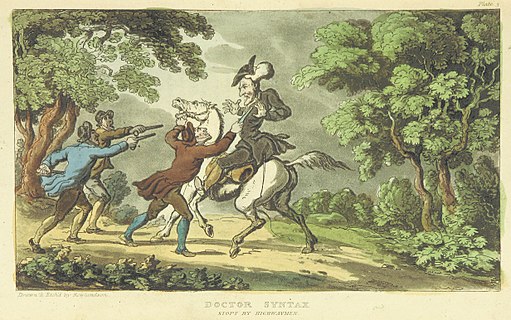

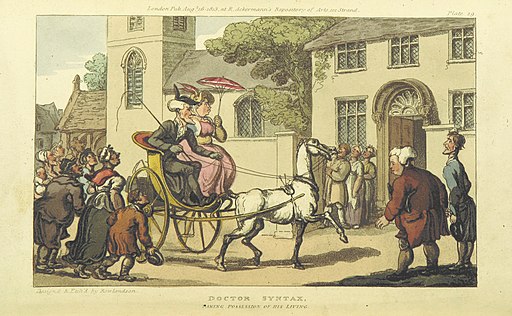

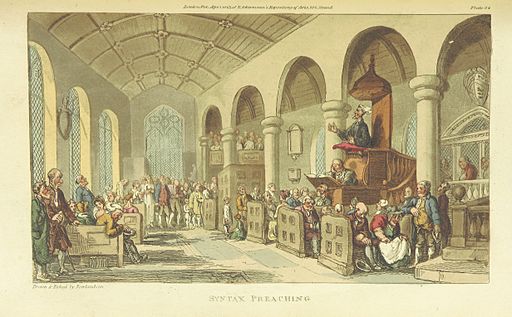

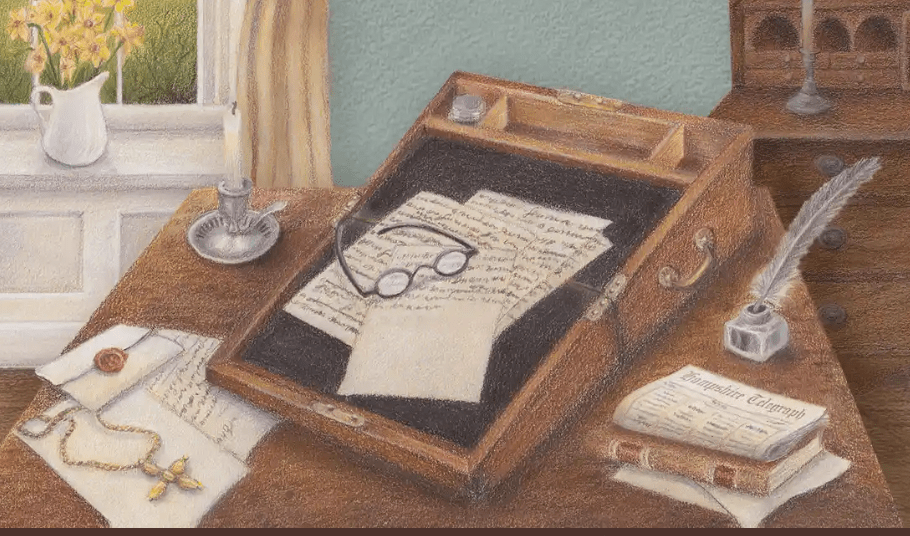

When you visit the room, you might want to start at the desk itself—Jane’s travel desk sits on a table. You’ll see manuscripts of several of the novels, which you can open and enjoy in early editions. Commentary tells more about the novel and the edition, with direct links to interesting sections like “Darcy’s list of desirable female accomplishments” and “Fanny asking about the slave trade.”

Nearby are newspapers, one of the most fun links. Several contemporary papers are included. You can hone in on a number of interesting articles, ranging from her brother Edward’s selling part of Stoneleigh Abbey, to reports of her brother Frank’s naval exploits, to the story of a swindler who pretended to be a rich person’s housekeeper!

The Bookshelf

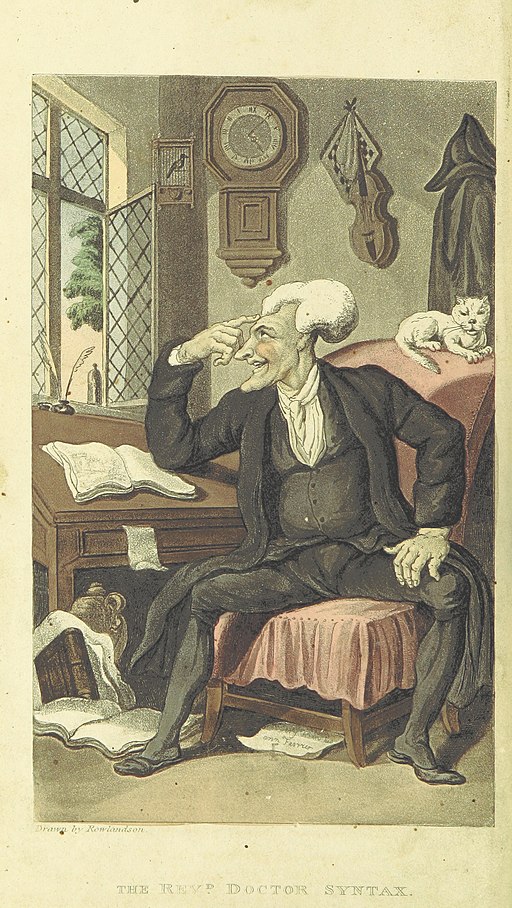

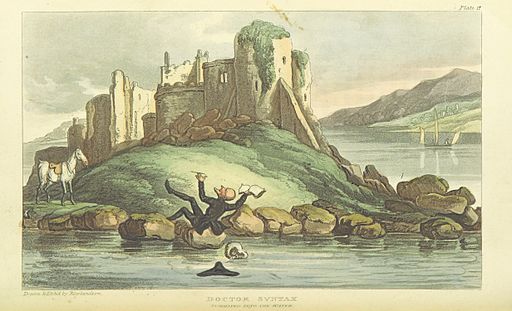

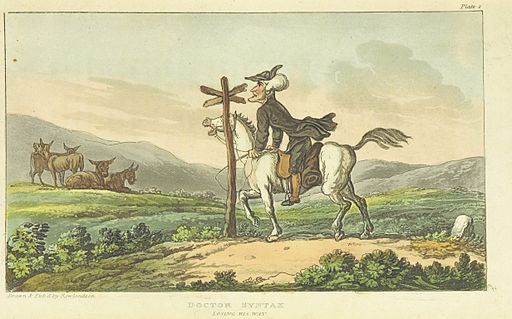

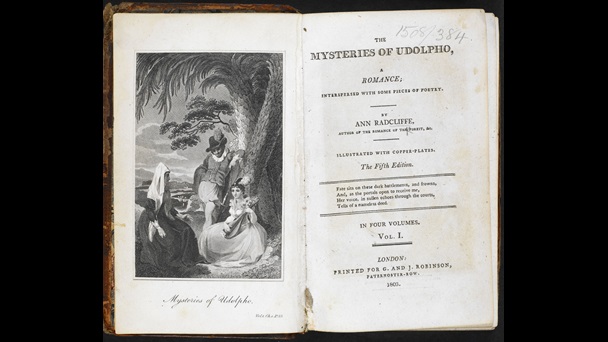

Click on the bookshelves in Rev. Austen’s bureau-bookcase , and you’ll see some books mentioned in Austen’s writings. I expect this will be expanded later. But for now, you can read from several authors Austen said she was “in love with”—Thomas Clarkson (on abolition), Sir Charles Pasley (on the military), and James and Horatio Smith (verse parodies). We also have a book that Fanny Price was reading, George Macartney on the British Embassy to China.

For each, you will find an easy-to-read early version of the book; clear commentary; pictures; and links to relevant passages in the novels and letters. Two also link to related articles. A great start if you want to explore these books connected to Austen!

Catalogs on the ledge of the bookcase open up to records of the Alton Book Society that Austen enjoyed. You’ll find lists of members, rules, and lists of the books that the members, including Austen, traded around. This gives us another peek into Austen’s life and reading.

Travels

A pianoforte stands next to the bookcase. It will eventually be connected to Austen’s music.

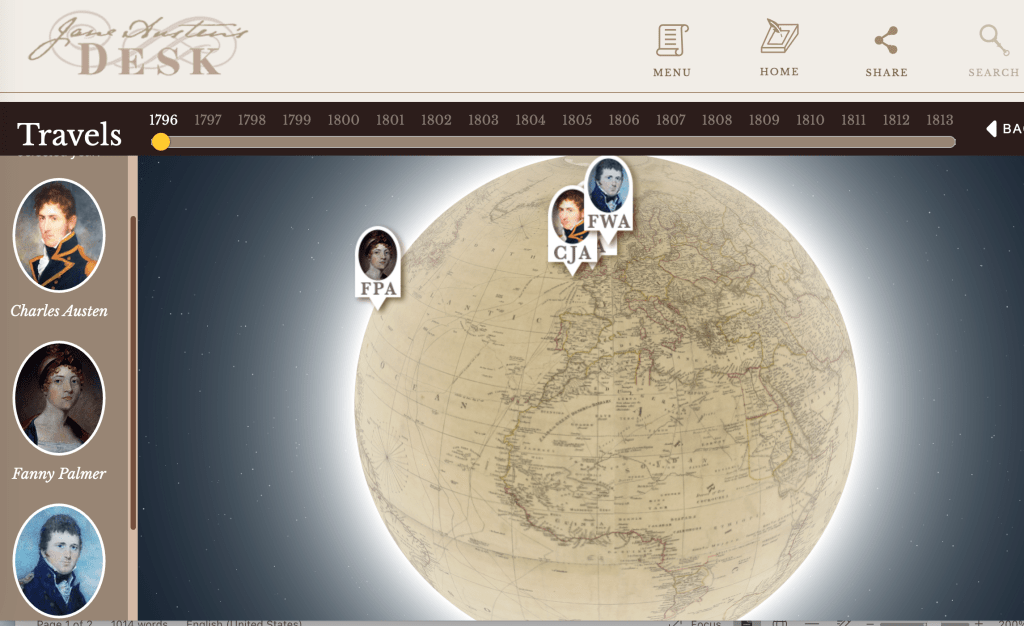

Above the pianoforte, click on the portrait of a ship on the sea. You go to a globe, where you can follow the travels of Austen’s family.

Silhouettes on the wall connect you to Jane Austen’s family tree. If you click on the orange “i”, you get more information about each person. The plus buttons reveal more generations.

Many of these features include audio commentary as well as written commentary. For example, Lizzie Dunford of Jane Austen’s House tells us about the topaz crosses Charles brought back for his sisters.

There are great possibilities for future additions.

An Interview with Inger Brodey

Inger Brodey, who runs the Jane Austen Summer Program, tells us more about the project:

JAW: Inger, what gave you the idea for doing this website?

Inger: I was interested in Austen’s own creative process, and also in countering the myth that she was not well informed in the science and politics of her day. I found a kindred spirit in Sarah Walton, who was a grad student when we started. In the 1990s, both Sarah and I had been enchanted by JK Rowling’s website with clickable, magical elements on her desk to interact with.

JAW: How is the website being funded?

Inger: We have received two rounds of funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, and have applied for more. We intend to create a GoFundMe or Kickstarter campaign to seek private funding to support specific new developments, such as the learning games we have in mind.

JAW: What are some parts you are excited about adding in the future?

Inger: The current setting is Spring 1813, while [Jane Austen] is writing Mansfield Park. Eventually we hope to add additional settings: for example, Summer or Winter 1814, when she was composing Emma; or Autumn, 1815, when Persuasion was in process.

JAW: What are some parts that you and your team are finding challenging?

Inger: Well, it all takes much more time to create than one would imagine. We have a great team of programmers and designers, including the wonderful Harriet Wu who has drawn the site by hand. We constantly try to find the sweet spot where we can appeal to both scholars and the general public, and to all ages. Just as with our Jane Austen Summer Program, we also focus on providing tools for educators who wish to bring Jane Austen into the classroom.

JAW: What other ideas do you have for expansion in the future?

Inger: As you can see on the site, there are many objects with potential to “animate” in the future. We are collaborating with Laura Klein to add music to the piano, Jennie Batchelor for sewing, and have plans for links to weather and agricultural information (via the scene out the window), tea culture (via the kettle), letter writing (via a folded letter), and many more.

We applied for a grant to develop a state-of-the-art platform for navigating, reading, notating, and analyzing Austen’s novels, including the potential for crowd-sourced editions.

As long as we can continue to find funding, I think this will be a lifelong project—there is so much potential to grow!

JAW: Thanks, Inger, we look forward to that!

The Desk, the Summer Program, and Online Talks

Gentle readers, I recommend you explore Jane Austen’s Desk. The website has not yet been configured for mobile phones, so you’ll need to access it on your computer or tablet.

When you’ve finished exploring, go back to the main page and take a survey, to possibly win a prize. The survey takes some thought and time, but you will get to give input for what you’d like to see in the future at this very helpful site.

The same Jane Austen Collaborative who created Jane Austen’s Desk also runs the Jane Austen Summer Program. This year it will be held June 19-22, 2025, in North Carolina. The theme is “Sensibility and Domesticity,” exploring “topics including medicine, birth, and domestic arts in Regency England and colonial North Carolina.” They will “focus on Austen’s first published novel, Sense and Sensibility—considering the birth of her career as a published writer as well as taking a transatlantic look at the world into which she was born.” I’m signed up, and would love to see some of you there!

Of course, even if you can’t get to North Carolina, you can always enjoy Jane Austen & Co.’s great offerings online. They are currently exploring Music in the Regency; I enjoyed a recent talk on Women & Musical Education in the Regency Era, by Kathryn Libin. Get on their mailing list for announcements of upcoming events.

They generously provide free access to recordings of their previous talks, on topics including “Austen and the Brontes,” “The Many Flavors of Jane Austen,” “Everyday Science in the Regency,” “Reading with Jane Austen,” “Asia and the Regency,” “Race and the Regency,” and “Staying Home with Jane Austen.” Something for everyone, it seems to me.

So much Jane Austen to enjoy!

Brenda S. Cox is the author of Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England. She also blogs at Faith, Science, Joy, and Jane Austen.