Gentle readers, some months back Lucy Warriner expressed an interest in writing about Mary Darby Robinson. This past week she submitted this wonderful post about a fascinating and successful woman who embodied the Georgian Era – wife, mother, actress, mistress, and writer. Enjoy. Mary Darby Robinson (1758–1800) was a woman of considerable talent. She was one of the leading English actresses of her day, and she also published several volumes of poetry and prose. Yet Robinson’s tumultuous love life often rivaled her professional accomplishments. She was unhappily married, and the press maligned her for her affairs with the Prince of Wales and Revolutionary War veteran Banastre Tarleton. Mary Robinson’s autobiography, first published in 1801 as Memoirs of the Late Mrs. Robinson, Written by Herself,sheds light on her fascination with the stage, which started at an early age and continued even after she became a full-time writer.

Bristol in the 18th century

Mary Darby, daughter of John Darby and Mary Seys Darby, was born in Bristol, England, on November 27, 1758. Her father pursued whaling in Labrador and America while she, her mother, and her four siblings remained in England. John Darby acquired a mistress, and after young Mary’s parents separated, the family finances were strained. However, John Darby intermittently funded his daughter’s education at schools in Chelsea, Battersea, and London. At Chelsea, teacher Meribah Lorrington fostered Mary’s love of reading and encouraged her when she began to write poetry.

Mrs. Robinson as Melania

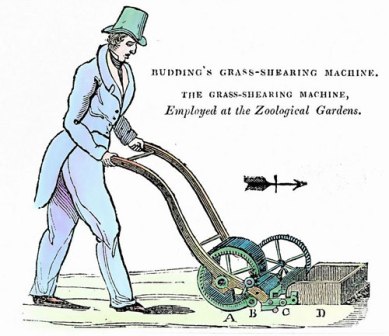

As a fifteen-year-old student at Oxford House in Marylebone, Mary was still drafting poems, even planning a great tragedy. This was a fitting development, for she had long shown a flair for the sentimental and dramatic. As a child, she had delighted in sad poetry and music, and she loved “the awful though sublime impression which the church service never failed to make upon [her] feelings” (Robinson, Memoirs 8–9). The recollection of seeing King Lear, the first play she ever attended, remained vivid throughout her life. In time, one of Mary’s teachers at Oxford House noticed her “extraordinary genius for dramatic exhibitions” (Robinson 31). The school dancing instructor, who was also employed at Covent Garden Theatre in London, put Mary and her mother in touch with Thomas Hull, the theatre manager. Hull, too, discerned Mary’s talent, and it was soon decided that her first performance would be opposite acclaimed thespian David Garrick in Lear.

David Garrick as King Lear, London, 1761. Image @UC, Berkeley

Garrick soon began coaching Mary for her debut, and she seems to have been his prize pupil:

Garrick was delighted with everything I did. He would sometimes dance a minuet with me, sometimes request me to sing the favourite ballads of the day; but the circumstance which most pleased him was my tone of voice, which he frequently told me closely resembled that of his favourite Cibber [singer and actress Susannah Cibber, who was a member of Garrick’s Drury Lane troupe from 1753 to 1766]. (Robinson 37)

But while Mary relished the charismatic actor’s tutelage, she was unable to take full advantage of it. In the midst of her training, Mary met Thomas Robinson, an aspiring legal assistant who endeared himself to Mrs. Darby by bringing her books and comforting her when her son contracted smallpox. He turned his attentions to Mary when she, too, developed smallpox. When she was almost sixteen, Mary accepted Robinson’s marriage proposal and gave up the chance to appear in Lear with Garrick. The couple married on April 12, 1774, and remained in London. When Thomas wanted the union to remain secret, the new Mary Robinson discovered that he was an illegitimate child with no prospect of inheritance and a great amount of arrears.

St. Martin in the Fields. Mary’s wedding was not so well attended.

Despite his penury, Thomas Robinson lived extravagantly. He took a mistress, Harriet Wilmot, and associated with debauched spendthrifts Lord Lyttleton and George Robert Fitzgerald, both of whom propositioned Mary. Deeply unhappy, Mary Robinson’s thoughts again turned to the theatre. Encountering accomplished thespian Mrs. Abington at a party, she “thought the heroine of the scenic art was of all human creatures the most to be envied” (Robinson 80). When creditors laid claim to the Robinsons’ possessions, the couple moved to evade them, at one point staying with Thomas’s father in Wales. Mary gave birth to Maria Elizabeth, her first child, in Wales on November 18, 1774.

Frances (Fanny) Abington by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1764-1773

Upon his return to London in 1775, police apprehended Thomas Robinson and confined him in King’s Bench Prison. Mary and Maria joined him there, and their imprisonment lasted little more than a year. While Thomas began an affair with the wife of a fellow inmate, Mary rebuffed further offers to become a kept woman. She devoted herself to raising Maria, transcribing legal documents for Thomas, and writing poetry. Prior to her incarceration, Mary had published Poems by Mrs. Robinson to help offset her husband’s debts. Though it had not sold well, she forwarded a copy to Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, a devotee of literature who sponsored writers. Mary Robinson soon became the duchess’s protégé.

William Breteton, by Henry Walton, 1780

Once her husband was freed from prison, Robinson resumed acting to provide for the family. Thomas, who had never finished his legal training, was no breadwinner. A chance encounter with Drury Lane actor William Brereton, who introduced her to theatre manager and famed playwright Richard Sheridan, returned Robinson to the theatrical milieu. While pregnant with her second child, Sophia, she read Shakespeare for Sheridan and won his approval. Garrick, Robinson’s old mentor, came out of retirement to coach her for the lead in Romeo and Juliet.

Drury Lane Theatre

In a flurry of nerves, she debuted at Drury Lane Theatre opposite Brereton’s Romeo in December 1776:

When I approached the side-wing my heart throbbed convulsively; I then began to fear that my resolution would fail, and I leaned upon the Nurse’s [the character of Juliet’s nurse] arm, almost fainting. Mr. Sheridan and several other friends encouraged me to proceed; and at length, with trembling limbs and fearful apprehension, I approached the audience. The thundering applause that greeted me nearly overpowered all my faculties. I stood mute and bending with alarm, which did not subside till I had feebly articulated the few sentences of the first short scene, during the whole of which I never once ventured to look at the audience. . . . The second scene being the masquerade, I had time to collect myself. I shall never forget the sensation which rushed upon my bosom when I first looked towards the pit. . . . All eyes were fixed upon me, and the sensation they conveyed was awfully impressive; but the keen, the penetrating eyes of Mr. Garrick, darting their lustre from the centre of the orchestra, were, beyond all others, the objects most conspicuous. As I acquired courage, I found the applause augment; and the night was concluded with peals of clamorous approbation. (Robinson 129–131)

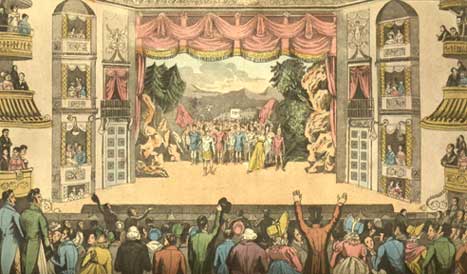

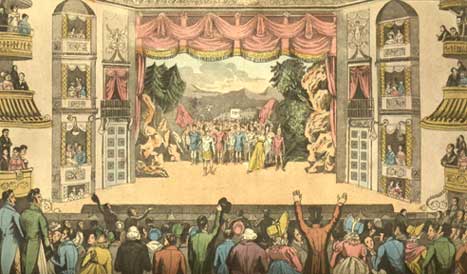

18th century actors on stage

Robinson’s appearance as Juliet led to a four-year acting career in which she starred in forty dramas, at times portraying several characters per week or per play. In February 1777, she followed her turn as Juliet with appearances in Alexander the Great and in Sheridan’s A Trip to Scarborough. The latter play was adapted from another work, and it elicited “a considerable degree of disapprobation” from audience members who had expected an original play (Robinson 132). Nevertheless, Robinson carried the day:

An audience watching a play at Drury Lane Theatre, by Thomas Rowlandson, ca. 1785

I was terrified beyond imagination when Mrs. Yates, no longer able to bear the hissing of the audience, quitted the scene, and left me alone to encounter the critic tempest. I stood for some moments as though I had been petrified. Mr. Sheridan, from the side wing, desired me not to quit the boards; the late Duke of Cumberland, from the stage box, bade me take courage: “It is not you, but the play, they hiss,” said his Royal Highness. I curtsied; and that curtsey seemed to electrify the whole house, for a thundering appeal of encouraging applause followed. The comedy was suffered to go on, and is to this hour a stock play at Drury Lane Theatre. (Robinson 132).

It is no wonder that Robinson claimed she “was always received with the most flattering approbation” (Robinson 133).

Mary Robinson in stage costume as Amanda, by Roberts Robins

Indeed, Mary Robinson was a prominent figure in a great age of theater. She observed that her time on the stage marked a period when dramatists and thespians were exceptionally gifted, when public enthusiasm about the theater was high, and when she and three other young actresses—Miss Farren, Miss Walpole, and Miss P. Hopkins—dominated their field. Robinson’s most acclaimed heroines were Juliet, Ophelia in Hamlet, Rosalind in As You Like It, and Palmira in Mahomet. Yet for all her renown, Robinson’s family never completely approved of her career. Her mother “never beheld [her] on the stage but with a painful regret” (Robinson 151). Her brother attended one of her performances but walked out when she took the stage. Robinson was somewhat relieved that her father was always abroad and never saw her perform.

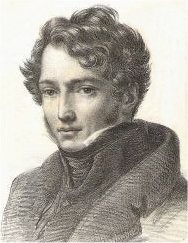

Richard Sheridan, by Sir Joshua Reynolds

In 1778, Robinson took time off from acting to give birth to Sophia and mourn the infant’s passing less than two months later . Sheridan, who had planned for her to star in The School for Scandal, was unfailingly supportive during her bereavement. Robinson considered him her “most esteemed of friends,” and she found his grief over Sophia’s death deeper than her husband’s (Robinson 153). When she was ready to work again, Sheridan helped find Robinson summer employment at Haymarket Theatre. However, a casting dispute with the director resulted in her receiving payment but never taking the stage.

Theatre goers: The laughing audience, Edward Matthew Ward, from an etching by William Hogarth made in 1733

Mary Robinson had returned to acting in 1779 when her life changed drastically. A twenty-one-year-old with many celebrated performances to her name, she was hopeful about her future. Though Thomas remained negligent, the Robinsons’ financial situation was improving. Ever concerned for Mary, Sheridan worried that she would exceed her income and/or have an affair with one of her many wealthy admirers, thereby jeopardizing her acting career. His fears were well founded. King George III and Queen Charlotte requested a performance of The Winter’s Tale, in which Robinson played Perdita. When the royal family attended the play on December 3, 1779, the seventeen-year-old Prince of Wales unashamedly admired her:

Mary Robinson as Perdita

I hurried through the first scene, not without embarrassment, owing to the fixed attention with which the Prince of Wales honoured me. Indeed, some flattering remarks which were made by his Royal Highness met my ear as I stood near his box, and I was overwhelmed with confusion. The Prince’s particular attention was observed by everyone. . . . On the last curtsy, the royal family condescendingly returned a bow to the performers; but just as the curtain was falling, my eyes met those of the Prince of Wales, and with a look that I never shall forget, he gently inclined his head a second time; I felt the compliment, and blushed my gratitude. . . . I met the royal family crossing the stage. I was again honoured with a very marked and low bow from the Prince of Wales. (Robinson 157-158) A few days later, Lord Malden (George Capel Coningsby) delivered Robinson a love letter from the Prince of Wales, who was an associate of his. The prince referred to her as “Perdita” and himself as “Florizel,” in the latter case referring to the prince in A Winter’s Tale who falls in love with Perdita. The press, which chronicled the relationship from its start, appropriated these names for their own use as well. Robinson at first refused to meet her new admirer, entering instead into an impassioned correspondence with him. Malden, who eventually fell in love with Mary himself, remained their reluctant go-between.

Caricature of the Prince of Wales as Florizel and Mary Robinson as Perdita, 1783

Eventually, the couple began meeting in person with third parties present, hoping to conceal the relationship until the prince was a legal adult. The prince guaranteed Robinson 20,000 pounds upon reaching his majority, and she left her husband and retired from acting.

At Vauxhall by Thomas Rowlandson. Mary Robinson stands at the right side on the front row, her husband (with cane) on one side and the Prince of Wales on the other.

Her last performance showcased her roles in The Miniature Picture and The Irish Widow. Robinson wept during the show, aware “that [she] was flying from a happy certainty, perhaps to pursue the phantom disappointment” (Robinson 177).

Caricature of Perdita and Charles James Fox (The Man & Woman of the People). He obtained an annuity for her from George III at the end of her affair with the prince.

Disappointment was, indeed, fast in coming. Before he formally and publicly acknowledged their love, Robinson received word from the prince that they could no longer see one another. He had given no prior indication of a change in his feelings, and all her attempts to contact him were unsuccessful. The press began lampooning Robinson mercilessly. Deeply in debt, she considered acting again but decided against it due to the general enmity against her. An invitation to meet the prince raised Robinson’s hopes, as did his renewed professions of love. But he quickly shunned her again, and their relationship was over by 1781. With the help of politician Charles James Fox, Robinson attempted to claim her promised 20,000 pounds, but in 1783 she instead accepted 500 pounds a year to make up for having abandoned her career.

Banastre Tarleton, miniature by Richard Cosway, 1782

After her disappointment with the prince, Robinson was linked romantically to Fox and Malden. Banastre Tarleton, a hard-living veteran of the American Revolution who moved in the same echelons as Malden, stole Mary away from him on a bet. Though sporadic, this relationship lasted for sixteen years, ending in 1798. As far as the press was concerned, it was the final blow against Robinson’s character. In 1784, at age twenty-four, she contracted rheumatism and developed paralysis that left her unable to walk. It is possible that botched treatment after she miscarried Tarleton’s child caused her condition. Robinson sought treatment in Germany and Flanders and returned to England in 1787.

Mrs Mary Robinson by George Romney

From the time she returned to England, Mary Robinson focused on writing and publishing. She wrote in a variety of genres, and her works were highly sought after due to the notoriety her love life had achieved. Poetry was a continuing interest for Robinson. She participated in the Della Cruscan movement that championed elaborate romantic verse; composed poems for the Morning Post, which also published Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s work; and published seven collections of her own verse between 1791 and 1800. Robinson also wrote eight novels, two of which alluded to her relationship with Tarleton.

Mary Darby Robinson by Thomas Gainsboroughm, 1781

Though they were less popular than her other projects, Robinson penned at least two works for performance. In the late 1780s, she was reputed to be composing an opera. If the rumors were true, no trace of the work survived. But the idea recalls Robinson’s youthful desire to write a tragedy. In 1793, she authored The Nobody, a play focusing on women gamblers. It was not her first foray into playwriting, for she had penned and acted in The Lucky Escape in 1778. Unfortunately, The Nobodymet with derision and only played for three nights before Robinson stopped production.

Mrs. Robinson from an engraving by Smith after Romney

Robinson’s last completed literary effort was A Letter to the Women of England, on the Injustice of Mental Insubordination, published in 1799. In it, she asserted women’s right to escape unhappy marriages, defending her own lifestyle in the process. Robinson was at work on her memoirs when she died on December 26, 1800. Maria Robinson edited the existing manuscript and continued the narrative from the point at which her mother began corresponding with the Prince of Wales. Memoirs of the Late Mrs. Robinson, Written by Herselfappeared in 1801, and a volume of verse, The Poetical Works of the Late Mrs. Mary Robinson, appeared in 1806. In 1895, Robinson’s memoirs were republished as Memoirs of Mary Robinson, this time with an introduction and footnotes by J. Fitzgerald Molloy.

Fronticepiece of Mary Robinson’s Memoirs

Mary Robinson’s autobiography provides an intriguing glimpse into eighteenth-century London’s theatrical circles. Though her acclaimed acting career was cut short, Robinson channeled her innate sense of the dramatic into writing. Her poetry and prose have garnered sporadic interest, only attracting scholarly attention over the last several decades. But Robinson’s autobiography has had enduring appeal. Perhaps this is because Mary Robinson was far more than a royal mistress, even though much of her notoriety was based upon this role. Instead of confining herself to the domestic sphere, she was at once a wife, mother, and career woman. By leaving her unfaithful husband and taking lovers, she flouted sexual double standards and affirmed women’s autonomy within marriage. Thus the study of this intelligent, rebellious, and troubled woman—at once an inspiration and a tragic figure—will likely endure for many years to come. About the author of this post: Lucy Warriner is a North Carolina animal lover and dance enthusiast. She is also an ardent admirer of Jane Austen. Bibliography

Image sources:

Read Full Post »