Great landed estates were symbols of the owner’s wealth and status in British society. Everything was put on grand display – from the exquisite architecture of the house itself to the furniture, jewels, silver plate, servants, books, carriages, horses, deer, game, forests, fields, and splendid grounds and gardens.

A fine estate certainly elevated a man in a lady’s estimation. Take this passage in Mansfield Park, written from Mary Crawford’s point of view:

Tom Bertram must have been thought pleasant, indeed, at any rate; he was the sort of young man to be generally liked, his agreeableness was of the kind to be oftener found agreeable than some endowments of a higher stamp, for he had easy manners, excellent spirits, a large acquaintance, and a great deal to say; and the reversion of Mansfield Park, and a baronetcy, did no harm to all this. Miss Crawford soon felt that he and his situation might do. She looked about her with due consideration,and found almost everything in his favour, a park, a real park, five miles round, a spacious modern-built house, so well placed and well screened as to deserve to be in any collection of engravings of gentlemen’s seats in the kingdom, and wanting only to be completely new furnished—pleasant sisters, a quiet mother, and an agreeable man himself—with the advantage of being tied up from much gaming at present, by a promise to his father, and of being Sir Thomas hereafter. ” – Mansfield Park, Jane Austen

(It is to Mary’s credit that, after this consideration, she prefered Edmund, the younger son, until she discovered that he intended to become a man of the cloth, and even then she did not give him up so easily.)

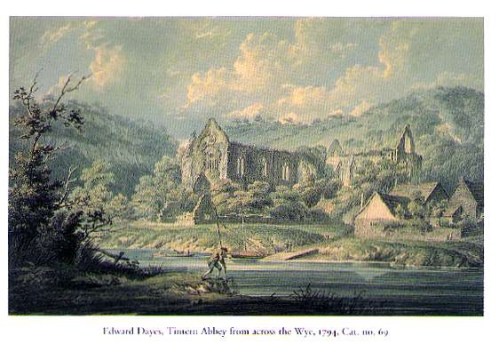

Visitors arriving at a landed estate took a circuitous route to the house along winding paths that were designed to show the grounds to their best advantage. They would pass through wooded areas and open fields, past lakes and rivers and herds of deer or cattle, and through a controlled wilderness area.

“The idea with Brownian landscapes is that you effectively go round them,” explains Mowl. “When [Capability] Brown did his landscape designs they would always have drives in them. They were an essential part of what he would do.” – The English Landscape Garden

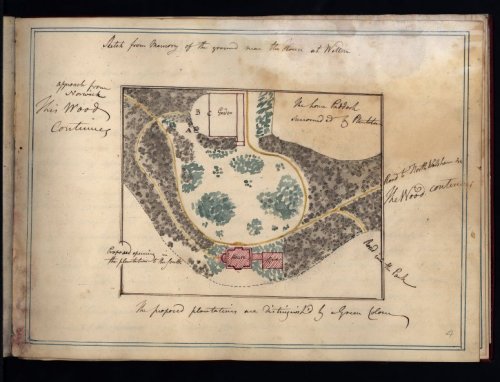

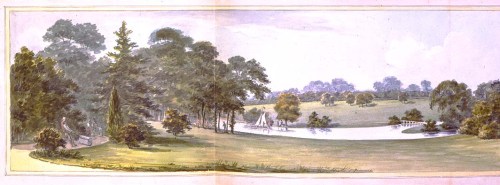

Witton approach from Norwich, 1801, Humphrey Repton Red Book. Image @University of Florida Rare Book Collection

Groundskeepers of extensive parks that featured winding drives and a variety of formal and ornamental gardens employed several means of keeping grass under control. Grazing sheep and cattle represented the first lines of defense. These herds were allowed to roam over vast expanses of land. Eighteenth-century romantic sensibility required that nothing as obviously artificial as a visible fence be allowed to contain them.

Highclere Castle is surrounded by park land designed by Capability Brown. Grazing sheep in the foreground.

A landscape feature called a Ha-Ha prevented grazing herds from coming too close to the house. The Ha-Ha, which consisted of a deep trench abutting a wall and which was hidden from casual view even at a short distance, allowed for the naturalistic features of romantic landscape gardening to take hold.

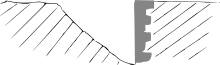

The Ha-Ha prevented grazing animals from crossing from one area of the estate to another. Image © John D. Tatter, Birmingham-Southern College

A Ha-Ha was so named because, as the myth goes, this landscape feature was so well hidden that an unsuspecting visitor would blurt out “ha-ha!” before falling into the trench. This cross section shows how the system worked.

The trenches of a Ha-Ha could sometimes be 8 feet deep.The primary view is from the right and the barrier created by the ha-ha becomes invisible from that direction and sometimes from both directions, unless close to the trench. Image @Wikipedia

Not all Ha-Ha’s prevented deer, sheep, or cattle from grazing up to the front of the house (though considering their droppings, one would thinks that this would be highly preferred.) At Petworth, the Ha-Ha was placed at the side of the house.

Petworth with Ha-Ha on the side of the house. Image @The English Landscape Garden

Built at the edge of a pleasure grounds surrounding a house, the ha-aha made a virtually invisible barrier that kept the cows and sheep in their pastures yet allowed uninterrupted views from house into park of from park into distant countryside. It meant that pleasure grounds, park and landscape could seamlessly become one. It is probably French in origin. Charles Bridgeman is generally credited with it’s introduction, but the first remnants of a ha-ha had already been installed at Levens Hall in Cumbria in 1689. – Architessica: Gardens and Landscapes

The transitional area between the formal gardens and the large park surrounding the house was known as the wilderness. This area was as meticulously planned as the other areas of the estate, but here the plantings were more irregular and included native plants and trees; gravel walkways; a pond, lake or river or all three; waterfalls; lawns that resembled meadows; and areas where the vistas were framed to deliberately look natural. If cottages and villages were required to be moved to achieve this picturesque effect, then so be it. The master’s will was done.

In Pride and Prejudice 1995, Elizabeth Bennet and Lady Catherine de Bourgh conduct their heated discussion in Longbourn’s “wilderness”. No grazing required here.

These wilderness areas were unique to topography and region, for each estate was uniquely different.

Nature in Herefordshire is not like nature in Lancashire and the garden style that tries to emulate the same form everywhere (particularly

one imported from another country entirely) is destroying what Pope had called the genius loci.” – (Wildness in the English Garden Tradition: A Reassessment of the Picturesque from Environmental Philosophy Author(s): Isis Brook Reviewed work(s): Source: Ethics and the Environment, Vol. 13, No. 1 (Spring, 2008), pp. 105-119)

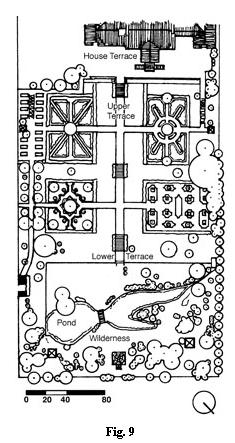

This plan of Paca Garden in Annapolis, MD, shows the formal gardens separated from the park by a wilderness area with pond, bridge, and follies. Image (a) Creating a Period Garden

Walking along a wilderness provided one with an endless variety of aesthetic experiences. Paths wended their way through woods that opened up to vistas. Large trees provided shelter for a bench or revealed moss growing on gnarly roots. Rivers, ponds, follies, and bridges provided natural sources of visual patterns. They were pleasant places to visit:

A ‘pleasant place’ is supposed to be naturally crafted. It’s a balance between two opposites: wanting to cultivate the land and letting it grow freely. However landscapers and architects finally accomplish this goal, the product always ends up being a beautiful oxymoron. – Landscape as Amenity

The exercise of walking along a wilderness ground was both visually and physically stimulating. These wilderness areas took years to design and arrange, with large trees moved from one area to another, buildings demolished or transported, and hillsides lowered or raised to “improve” the view.

Such improvements, as they were generally known, required meticulous planning and strenuous effort. Master landscape gardeners like Lancelot “Capability” Brown and Humphry Repton became household names. Jane Austen knew about such efforts and their resulting changes:

Mr. Rushworth, however, though not usually a great talker, had still more to say on the subject next his heart. “Smith has not much above a hundred acres altogether, in his grounds, which is little enough, and makes it more surprising that the place can have been so improved. Now, at Sotherton, we have a good seven hundred, without reckoning the water meadows; so that I think, if so much could be done at Compton, we need not despair. There have been two or three fine old trees cut down that grew too near the house, and it opens the prospect amazingly, which makes me think that Repton, or anybody of that sort, would certainly have the avenue at Sotherton down; the avenue that leads from the west front to the top of the hill, you know,” turning to Miss Bertram particularly as he spoke. But Miss Bertram thought it most becoming to reply—

“The avenue! Oh! I do not recollect it. I really know very little of Sotherton.”

Fanny, who was sitting on the other side of Edmund, exactly opposite Miss Crawford, and who had been attentively listening, now looked at him, and said, in a low voice—

“Cut down an avenue! What a pity! Does it not make you think of Cowper ?’ Ye fallen avenues, once more I mourn your fate unmerited.'”

He smiled as he answered, ” I am afraid the avenue stands a bad chance, Fanny.”

“I should like to see Sotherton before it is cut down, to see the place as it is now, in its old state , but I do not suppose I shall.” – Mansfield Park, Jane Austen

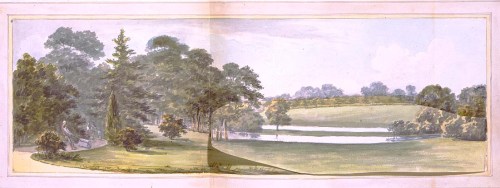

Sir Humphrey Repton, Whiton (Before) Image @British Architecture

Sir Humphry Repton left a valuable legacy with his Red Books. It was his habit to sketch before and after landscapes for his customers and present the drawings to them bound in red covers. His improvements for Whiton are subtle but important. Two parallel streams have been turned into a serpentine lake with a waterfall at one end. The distant fields provide a focal point with artfully arranged trees. If you look closely at the gravel path on the left, you can spy a gardener.

Sir Humphrey Repton, Whiton (After). Image @British Architecture

The samples below of Ferney Hall from The Morgan Library and Museum show the before and after drawing of an improved vista in which, using Jane Austen’s words, ” a prospect was opened”.

The after image provides a glimpse of a folly. Instead of acting as a barrier, the woods give way to the scene, which provides a pleasant stopping point for the wanderer to sit and view. While such scenes looked natural, they were not.

Though visually the wild and the domestic were one is the same, “these were carefully managed scenes, designed to look natural, but actually contrived on a vast scale” – Landscape as Amenity

The wilderness was designed some distance from the house. Approaching closer, the visitor would see a more formal arrangement of fountains and shrubbery and mazes and flower gardens.

Chawton House: View from the wilderness towards the house and more formal plantings. Image @Tony Grant

The gentlemen who had these gardens designed for them had all been on the Grand Tour and learned the classics,” says Timothy Mowl of the University of Bristol. “It was part of their make-up and they wanted to display their taste and learning within gardens.” – The English Landscape Garden

Landscape designs informed the process of maintaining the grounds. Large estates employed many gardeners to keep cricket and croquet fields in pristine condition, cultivate the ornamental and kitchen gardens, and oversee the orchards and hot houses. The question is: How did they do it?

Extensive gardens surrounding Wrest House in Bedfordshire. Wrest Park Gardens are spread over 150 acres (607,000 m²) near Silsoe, Bedfordshire, and were originally laid out in the early 18th century, probably by George London and Henry Wise for Henry Grey, 1st Duke of Kent, then modified by Capability Brown in a more informal landscape style, without sacrificing the parterres. Image from The Leisure Guide

As mentioned before, the first line of defense was allowing herds of sheep and cattle to graze. However, their by-products left something to be desired. (If anyone has ever walked through a cow pasture, they will know what I mean.)

English Garden at Leeds: Artfully contrived to look both contained and natural. Image @Landscape Into Land

Lawn mowing and ornamental landscaping held no particular interest to 99% of the people who lived during the Georgian era. Cottagers and town dwellers maintained small plots of vegetable gardens and laborers worked in the fields, using scythes to cut wheat and grain for their employers.

18th century method for harvesting grain with scythes. Image @Our Ohio

The laborers wielding scythes in the above image provide a clue to how grass was clipped – using a smooth, well-rehearsed motion, they worked in teams to cover large areas of ground. Their labor was cheap and they followed a system that included working in the morning when the ground was still damp.

To prepare the lawn for scything, a gardener would:

“pole” the lawn first (swishing a long whippy stick across the grass to remove wormcasts) and … roll the ground to firm it and set the blades of grass in a uniform direction.” – Notes and Queries, The Guardian UK

19th Century Coalbrookdale Roller. Rolling the lawn tamped down the grass and seed, and promoted growth and strong roots. Image @jardinique.co.uk

The secret to maintaining a close-cropped lawn was to trim it frequently, about once a week. Lawn edges were best trimmed with sheep shearing clippers.

The grass was kept free of daisies with an instrument named a daisy grubber, which is the long-handled instrument with angled pick in the image below. Daisy grubbers are still sold today, as they apparently do the job well.

Dibbles and daisy grubber. Image @Garden History -Tools the Dibble

Dibbles were used to dig holes in the ground to plant seeds or bulbs, pry up roots, or jab weeds out between bricks and stone.

Even with these instruments, maintaining these large gardens took intensive labor. One can just imagine how much work was involved in protecting tender plants from insects and marauders, early frosts, and dry spells; and forcing exotic fruits and vegetables to grow out of season in hot houses.

While improvements were made over the course of the 19th century, some customs remained the same:

“rich people used to show their wealth by the size of their bedding-plant list: 10,000 plants for a squire; 20,000 for a baronet; 30,000 for an earl and 50,000 for a duke. ” – Ernest Fields, Life in the Victorian Country House by Pamela Horn, p. 75.

Landed owners showed off their wealth through a variety of means, including the number of servants they employed.

It was not unusual for a great estate to employ 60 – 100 gardeners. There was the full-time staff, consisting of a master gardener, who had begun his apprenticeship as a boy, and his assistants.

Scottish gardeners were preferred, as it was thought that they had received the best training. Unmarried apprentice gardeners moved from estate to estate in order to gain experience and be promoted.

Junior staff worked long hours, around 60 hours a week, for, in addition to their gardening duties, they had to maintain the temperatures in glassed-in conservatories and meticulously care for archery, cricket, bowling and croquet lawns.

The master gardener hired local labor seasonally to help during peak times, so the number of laborers fluctuated.

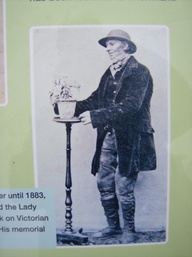

The head gardener at the Thornham estate in Sussex at the end of the 19th century. Image by kitchen915

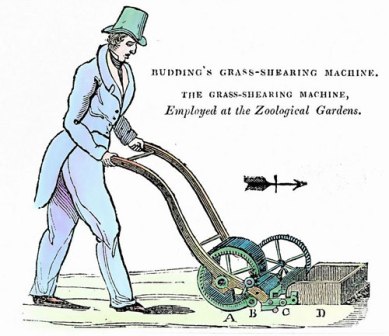

With improvements in gardening equipment, including the invention of the lawn mower in 1830 by Edwin Beard Budding, machines began to take over the hard work of the scythe men.

First lawnmower invented by Edwin Beard Budding. Image @The Chronicle of Andrew Jackson, Wikispaces

I imagined a Regency gentleman pushing one in his regalia, and found this wonderful advertisement. After Budding’s initial invention, a variety of lawn mowers were invented, each improving on the other.

Mowing a lawn in 1832. Credit: Ann Ronan Picture Library / Heritage Images

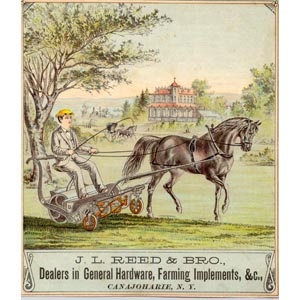

Needless to say, large areas of lawn needed a more efficient method of keeping the grasses trimmed. As the 19th century progressed, horses were employed to pull large lawn mowing machines.

Horse pulling a lawn mower. Image @The Cultural Landscape Foundation

They wore special leather over shoes to protect fragile lawns, such as those shown in the image below.

This short video on YouTube demonstrates how 18th century gardeners dealt with sudden cold snaps.

More on the topic: