By Brenda S. Cox

“. . . perhaps you would not mind passing through London, and seeing the inside of St. George’s, Hanover Square. Only keep your cousin Edmund from me at such a time: I should not like to be tempted.”—Mary Crawford, Mansfield Park, chapter 43

Mansfield Park includes much more discussion of the church than any other Austen novel. Not surprisingly, it also names more real churches than the other novels do.

In an earlier post we explored the Garrison Chapel, where Fanny Price and her family worship in Portsmouth. Henry Crawford attends with them on his visit. Perhaps this symbolizes his attempts to reform himself and become worthy of Fanny; attempts that ultimately fail.

Henry’s sister Mary names another real church in a letter to Fanny. She wants Fanny to let her and Henry take Fanny back to Mansfield from Portsmouth, where Fanny has been staying with her family. Fanny is unhappy and unhealthy, but will not commit the impropriety of going back to Mansfield Park before her uncle sends for her. Mary wants to take Fanny to see Henry’s estate and then pass through London on the way to Mansfield.

She suggests visiting St. George’s, Hanover Square. This was a popular church for weddings among the upper classes of London. Mary hopes Fanny will marry Henry there. At the same time, Mary says it might tempt her to marry Edmund. She doesn’t want to marry a clergyman, or a second son who will not inherit an estate, but she is attracted to Edmund.

St. George’s, Hanover Square Today

During a recent visit to London, I had the privilege of worshiping at St. George’s, Hanover Square on a Sunday morning. The service was a Sung Eucharist, a Communion service in traditional language, with beautiful singing from the choir and impressive organ music. During the service, the congregation renewed their baptismal vows.

The church also offers brief midday services from the Book of Common Prayer on weekdays and several other Communion services during the week. Weekday “Morning Calm” services are held during termtime, as “a short period of reflection, contemplation, and relaxation before the challenges of the day begin.”

Nowadays the area around Hanover Square is mostly offices and businesses. I was told that most people in the current congregation live farther away, since few people live close to the church now.

Wealthy Mayfair

Hanover Square is in Mayfair. In Austen’s England, many wealthy people had large houses in Mayfair or surrounding areas. In Sense and Sensibility, the Palmers live in Hanover Square, while the Middletons, Mrs. Ferrars, and Willoughby live nearby in Mayfair. Mrs. Jennings and John and Fanny Dashwood live in Marylebone, an area just north of Mayfair. It developed when Mayfair could no longer accommodate all those who wanted fashionable, elegant housing. (Source: The Annotated Sense and Sensibility, David Shapard.)

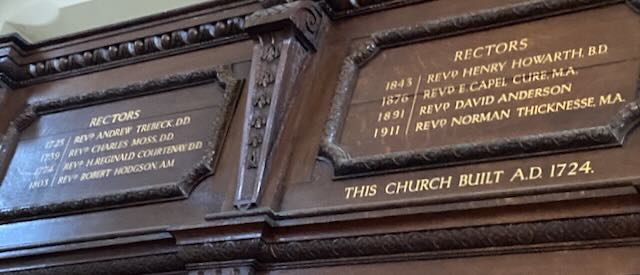

St. George’s is the parish church of Mayfair, where the wealthy worshiped. In 1711, Parliament had passed an Act for the building of fifty new churches in and around London. The wealthy of Mayfair petitioned for a church, which was completed in 1725. The patron saint of the church is St. George, a Christian martyr of the third century who is also the patron saint of England.

The parish was large, with a vestry of 101 vestrymen. These included 7 dukes, 14 earls, 7 barons, and 26 other titled people. A vestry, led by the church’s rector and churchwardens, decides matters relating to the church and the secular parish. (Mr. Knightley, Mr. Weston, Mr. Cole, and Mr. Cox are apparently on the vestry for their parish, as they are “busy over parish business” in Emma.) The St. George’s, Hanover Square vestry dealt with local issues including street lighting, refuse disposal, nightwatchmen, and a workhouse for the poor.

Rich and Poor

While the wealthy owned mansions in the area, most spent only the winter in London, passing the rest of the year on their country estates. The back alleys behind the mansions teemed with poverty and misery year-round. In the early 1800s, the Evangelical movement began to awaken the church to the needs of the poor. St. George’s established a parish school for poor children in 1804, supported by public subscriptions. Later in the century, the church initiated and supported extensive projects to help the working classes of the area.

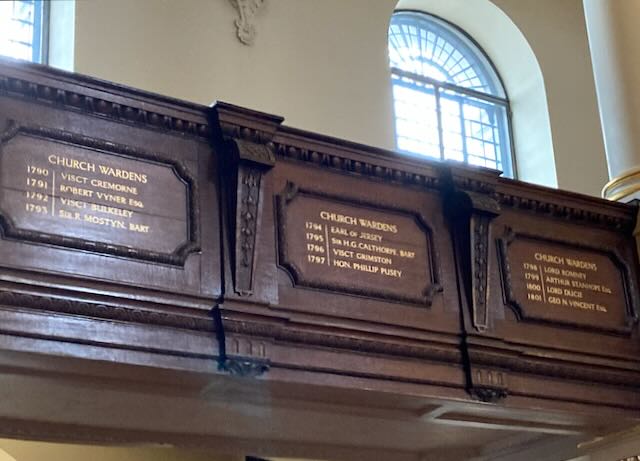

But the wealthy ran the church in Austen’s time. Around the gallery (balcony) are listed the churchwardens, year by year. Anglican churches generally have two elected churchwardens, responsible for financial accounts, movable property of the church, keeping order, and other administrative responsibilities. The churchwardens listed on St. George’s galleries for the 1700s and early 1800s sound impressive: Viscounts, Earls, Lords, Sirs, Honorables, and Esquires.

Music

The composer George Friderick Handel lived about a four minute walk from the church. He helped choose the organ and organist for the new church. He had a pew there and worshiped at St. George’s until he died. He wrote the Messiah in his house nearby on Brook Street, which is now a museum.

Weddings

Since it was at the heart of the wealthy district, St. George’s, Hanover Square was the popular place for weddings of the wealthy and influential. In 1816, the church hosted 1,063 weddings! Famous people including Percy Bysshe Shelley, Benjamin Disraeli, George Eliot (Mary Lewes), and Theodore Roosevelt were married at St. George’s. Mary Crawford was likely staying near there with her wealthy London friends, and she may have attended church there. So it was the first place she thought of for her own and her brother’s weddings. It is still a popular venue for weddings, though not as much so as in Austen’s time.

On Thursday, we’ll look at the other two real churches mentioned in Mansfield Park, the two most famous churches in England. Do you know which ones they are? We’ll also consider which London church Lydia and Wickham married in!

All images above ©Brenda S. Cox, 2025.

Churches mentioned by name in Jane Austen’s novels and letters

St. Swithin’s, Walcot and other churches in Northanger Abbey

London Churches in Austen’s Novels

St. Paul’s, Covent Garden: Actors’ Church

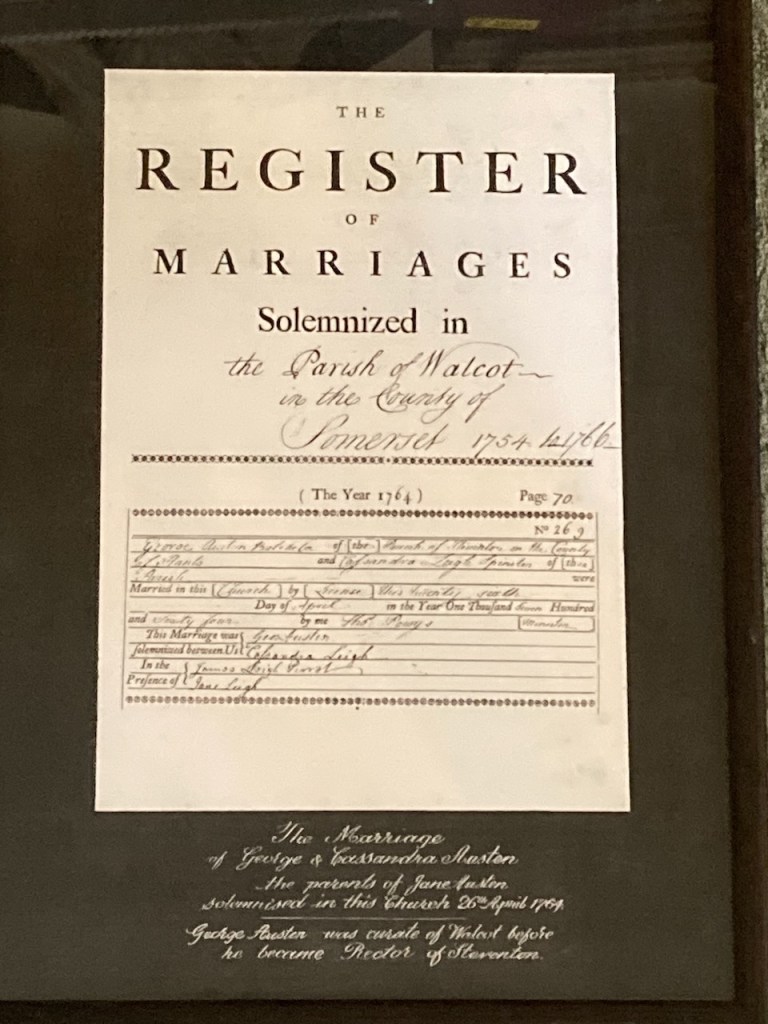

Austen Family Churches

Hamstall Ridware and Austen’s First Cousin, Edward Cooper

Adlestrop and the Leigh Family

Stoneleigh Abbey Chapel and Mansfield Park