Downton Abbey, a PBS Masterpiece Classic mini-series, is as much a tale about the servants below stairs as about the noble Earl of Grantham and his family who employed them. With the recent airing of the updated version of Upstairs Downstairs in Great Britain, I am sure a debate will long rage about which series portrayed their eras and class differences better. In both cases, the viewer is the winner.

Downton Abbey (Highclere Castle, an “Elizabethan Pile”) Credit: Courtesy of © Carnival Film & Television Limited for MASTERPIECE

Images Credit: Courtesy of © Carnival Film & Television Limited for MASTERPIECE

No matter how expertly this mini-series of Downton Abbey tries to portray this bygone era, it is nearly impossible to capure life in an Edwardian country house exactly as it once was. The viewer should be aware that we can glimpse only a faint, musty, museum shadow of the complex and thriving community that a great English estate once supported.

The Crawleys and the servants of Downton Abbey. Credit: Courtesy of © Carnival Film & Television Limited for MASTERPIECE

Images Credit: Courtesy of © Carnival Film & Television Limited for MASTERPIECE

It is a well-known fact that grand country houses could only be run with a great deal of help. As early as the 18th century, Patrick Colquhoun estimated that there were around 910,000 domestic servants (in a population of 9 million). By 1911, the number of domestic servants had risen to 1.3 million. Eighty percent of the land during the Edwardian era was owned by only 3% of the population, yet these vast estates were considered major employers.

The earl (Hugh Bonneville) and his heir, Matthew Crawley (Dan Stevens), survey his vast estate. Credit: Courtesy of © Carnival Film & Television Limited for MASTERPIECE

In the grander and larger houses, the ratio of servants (both indoor and outdoor) to the family could approach 1:7 or 1:10, but as the industrial revolution introduced improvements in laundering, lawn maintenance, and cooking, the number of servants required to run a great estate was greatly reduced.

The earl and his heir, Matthew Crawley, survey the cottages and outer buildings on his estate. Credit: Courtesy of © Carnival Film & Television Limited for MASTERPIECE

After World War One and the rise in taxes for each servant employed, many great families no longer kept two sets of house staff. They began to bring servants from their country house to their house in Town, leaving only a skeleton crew behind to maintain the family seat in their absence.

Grounds of Downton Abbey (Highclere Castle)

Country estates were designed to showcase the owner’s wealth via collections of art, furniture and other luxurious possessions, such as carriages, lawn tennis courts, and the like. The main house sat at the end of a long and winding drive through acres of beautifully landscaped park lands.

The Duke is greeted by both the family and the servants. Credit: Courtesy of © Carnival Film & Television Limited for MASTERPIECE

The spectacle did not end there, for approaching the house, guests would see a grand facade or an equally imposing flight of stairs that led to the first floor (or both). In Downtown Abbey, the family awaited the arrival of the Duke of Crowborough (Charlie Cox) along with their servants, who were arrayed in line according to their station.

The servants await their new masters at Norland. Sense and Sensibility, 2008.

Such a display of staff was also evident in the 2008 adaptation of Sense and Sensibility, when Fanny and Robert Dashwood arrived to claim Norland Park.

Grand interior hall of Downton Abbey, floor leading to the private rooms. Credit: Courtesy of © Carnival Film & Television Limited for MASTERPIECE

Once introductions had been made, the guests would ascend the imposing stairway and enter an equally impressive high-ceilinged hall that contained yet another grand staircase, which led to the private rooms upstairs. The ladies customarily brought their own maids, who would also require lodging. (In Gosford Park, a poor female relation had to make do with one of the hostesses’ house maids to help her with her dress and hair.)

Thomas (Rob James-Collier), the first footman, is chosen to act as valet to the duke. Credit: Courtesy of © Carnival Film & Television Limited for MASTERPIECE

The guests’ servants were expected to enter the house through a separate, back servant’s entrance, and shared quarters with the regular staff. The host supplied his own butler or footmen to help serve as valet to his male guests.

The Earl of Grantham’s impressive library/study. Credit: Courtesy of © Carnival Film & Television Limited for MASTERPIECE

A host’s willingness to lavishly entertain his guests did not necessarily reflect the family’s daily schedule:

In 1826 a German visitor to England remarked that: it requires a considerable fortune here to keep up a country house; for custom demands… a handsomely fitted-up house with elegant furniture, plate, servants in new and handsome liveries, a profusion of dishes and foreign wines, rare and expensive desserts… As long as there are visitors in the house, this way of life goes on; but many a family atones for it by meagre fare when alone; for which reasons, nobody here ventures to pay a visit in the country without being invited, and these invitations usually fix the day and hour… True hospitality this can hardly be called; it is rather the display of one’s own possessions, for the purpose of dazzling as many as possible.(3)” – The Country House: JASA

Travel in winter, Henry Alken, 1785

Guests stayed for a long time for a variety of reasons. In the 17th and 18th centuries, travel over a long distance was laboriously slow and difficult, for roads were notoriously poor and dangerous. Long visits, such as Cassandra Austen’s visits to her brother Edward in Godmersham Park, became a custom. Even during the Edwardian age, when travel was much improved, guests tended to stay for the weekend (Saturday through Monday). In Downton Abbey, the Duke of Crowborough arrived amidst much hope and anticipation, until he discovered that the estate had been entailed to a third cousin not the earl’s daughter, whom he had come to woo, and he cut his visit to one short day and evening, making an excuse that did not hold water.

Catherine Morland (Katherine Schlessinger) and Eleanor Tilney (Ingrid Lacey), Northanger Abbey 1986

Even during the 18th century, when long-term guests were expected, some overstayed their welcome, like Jane Austen’s anti-heroine, Lady Susan Vernon, whose hostess (sister-in-law) despised her but was forced to tolerate her because she was ‘family.’ Desirable guests, like Catherine Morland of Northanger Abbey, were invited to extend their visit. In Catherine’s instance, Eleanor Tilney, a motherless young lady who lived without a female companion, found the young girl’s company delightful. By the time General Tilney discovered that Catherine was no heiress, she had been with the Allens in Bath and the Tilneys in Northanger Abbey for a total of 11 weeks. As previously noted, Edwardian hosts, while generous, expected house guest to stay for only three days. During this time every luxury was lavished upon them, but it was considered bad form if they stayed longer than arranged or without invitation.

Breakfast was a substantial meal served at 9:30 a.m. Credit: Courtesy of © Carnival Film & Television Limited for MASTERPIECE

At set times, Edwardian guests would congregate in the common rooms, which included the drawing room, music room, dining room and breakfast room, the library or study, the gallery (where ancient family portraits were hung), the billiard room, and the conservatory. Vast lawns and gardens were laid out for promenading; guests could ride or walk through the parklands to view picturesque follys or dine alfresco (outdoors), take tea under an awning, or paint a vista or two.

Taking tea alfresco. Credit: Courtesy of © Carnival Film & Television Limited for MASTERPIECE

The reputation of a host rested on the entertainments, which helped to pass the time – walking, riding, shooting (in winter), and hunting (in fall) for outdoor activities; and card parties, musicales, and dances for indoor festivities. A fox hunt, such as the one depicted in Downton Abbey, required riding skill and stamina, for the chase would take riders over hills and dales, and hedges, and over long distances for much of the day.

The hunt required riding skills and stamina.Credit: Courtesy of © Carnival Film & Television Limited for MASTERPIECE

Billiards made an appearance during the 17th century, and by the 19th century billiard rooms had become a staple. Private libraries offered a variety of books and periodicals. In the summer, Edwardians enjoyed lawn tennis, croquet, cricket, and golf (by the men).

The male guests in Regency House Party (2004) could pretty well behave and move around as they pleased.

Ladies and gentlemen tended to spend the day apart. Male guests were more active and could engage in almost any activity during the day, except at the time reserved for dinner, when they were expected to show up. In an Edwardian house, men did not escort their female dining partners into the dining room. Rather, after the host served cocktails in the drawing room a half hour before the meal, the group moved to the dining room where they were seated according to a set pattern, with guests sitting between members of the family and their neighbors.

The new heir of Downton Abbey (Dan Stevens) sits next to his hostess, the Countess of Grantham (Elizabeth McGovern). Credit: Courtesy of © Carnival Film & Television Limited for MASTERPIECE

After dinner, the ladies would remove to the drawing room, which became increasingly larger and more feminine over time, while the gentleman relaxed at the dining room table, drinking port, smoking their cheroots, and discussing manly topics.

The drawing room at Downton Abbey was large and feminine. Credit: Courtesy of © Carnival Film & Television Limited for MASTERPIECE

While an 18th century gentlemen would have talked about horse flesh and carriages, Edwardian guests would have included automobiles and their rapidly changing technology, road improvements, and the availability of petrol as well.

Transportation was changing rapidly at the turn of the 20th century. Credit: Courtesy of © Carnival Film & Television Limited for MASTERPIECE

Unlike the gentlemen, a lady’s day was more restricted and confined. She spent her day following a set routine, starting with breakfast, and wearing appropriate outfits and getting into them and out of them. Mothers spent some time overseeing the nannies and the care of their children (if they were brought along). Ladies, married or not, would also receive visitors, sew, gossip, read, walk, participate in charity work, observe the men at sport (if invited) or take a ride in the carriage. They did join in on more active, outdoor games at set times during the appropriate season, such as cricket, croquet, lawn tennis, lawn bowling, and the like, but they would have been properly dressed for the occasion.

The head maid (Joanne Froggatt) dresses Lady Mary’s (Michelle Dockery) hair for dinner. Credit: Courtesy of © Carnival Film & Television Limited for MASTERPIECE

Imagine poor Eleanor Tilney in the late 18th century, alone in a grand house without female companionship, having no-one to talk to and forced to live a constricted life. No amount of walking, charity work, practicing the piano, or overseeing the household would have made up for her boredom, and thus Catherine Morland’s companionship was so welcome.

Manor House (2002), dressing Lady Olliff-Cooper. Image @PBS

In Regency House Party (the 2004 mini-series), the modern women who portrayed Regency ladies chafed under the strict rules of protocol, forced chaperonage, and daily tedium. A lady’s routine did not much improve during the Edwardian era, although towards the end of this period changing one’s gown for afternoon tea became obsolete.

Tea gown, circa 1908. Image @Vintage Textiles

In Manor House, the 2002 mini-series set in the Edwardian era, Lady Olliff-Cooper’s spinster sister, the lowest-ranking member of the family, had so little to do and so little say in how she could spend her time, that Avril Anson (who in real life is a professor) left the series for a few episodes to maintain her sanity.

Evelyn Napier (Brendan Patricks) and Matthew Crawley (Dan Stevens) eye their rival before dinner. Credit: Courtesy of © Carnival Film & Television Limited for MASTERPIECE

Lady Olliff-Cooper … [needed] to change her clothes five or six times a day. And very few of these dresses would be what today we’d call practical. Not only did each meal carry its own dress code, but if she needed to receive a visitor, pay a call or go riding, she’d have to change both her clothes and often her hairstyle as well.” Manor House, clothes

Anna Olliff-Cooper, who portrayed the lady of the house in Manor House, spent an enormous amount of her day changing into new gowns and having her hair dressed. She would stand passively as her maid did all the work. Anna noted how constricting the dresses were, and cried as she described how the tight sleeves of her gowns prevented her from raising her arms above her shoulders or from closely hugging her eleven-year old son. Even the fashions conspired to keep a women passive!

The Dinner Party, 1911, Jules Alexandre Grun

After they had finished their cigars and port, the gentlemen were obligated to rejoin the ladies for cards or music, or both, to while away the evening. The Duke’s behavior in Downton Abbey was egregious, for instead of joining the group for the rest of the evening, he went to bed early. The house party would stay up until 10:30 or so (unless a grand ball had been arranged, and then the guests would stay up until the wee hours of the morning).

Male conversation after dinner over port and cigars. The duke and earl have a frank conversation. Credit: Courtesy of © Carnival Film & Television Limited for MASTERPIECE

In either case, the last people in the house to retire for the night would be the servants, but their lives and schedule will be described in another post.

Look for Downton Abbey, Part One to air on PBS Masterpiece Classic on Sunday, January 9th! Once again PBS will host a twitter party! Stay tuned for details.

End of the day at Downton Abbey. Credit: Courtesy of © Carnival Film & Television Limited for MASTERPIECE

More on the topic:

Images of Downton Abbey Season 1: Credit Courtesy of © Carnival Film & Television Limited for MASTERPIECE

Read Full Post »

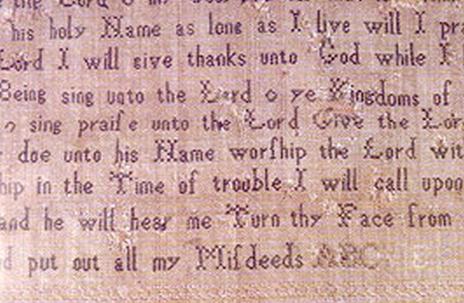

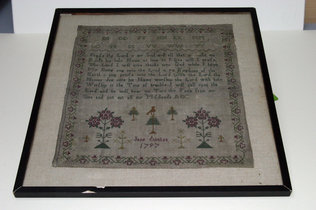

The Bodleian Library in Oxford recently exhibited a sampler (along with other items) for one day to celebrate World Book Day on March 1. This linen cross stitch sampler, purportedly made by a 12-year-old Jane Austen in 1787, was displayed for the very first time. The stitching has become frayed and undone, so that the sampler appears to have been made in 1797. A stylized border with flowering trees surround the words to the psalm, “Praise the Lord O my soul.”

The Bodleian Library in Oxford recently exhibited a sampler (along with other items) for one day to celebrate World Book Day on March 1. This linen cross stitch sampler, purportedly made by a 12-year-old Jane Austen in 1787, was displayed for the very first time. The stitching has become frayed and undone, so that the sampler appears to have been made in 1797. A stylized border with flowering trees surround the words to the psalm, “Praise the Lord O my soul.”