Jane Austen’s mother, Cassandra’s

features were aristocratic; her hair was dark and her eyes an unusual tint of grey. She had an instinctive tendency to depreciate her own appearance; it was her elder sister Jane, she always insisted, who was the beauty of the family. But Cassandra did admit to a certain vanity concerning her fine patrician blade of a nose.” – Jane Austen, a family record by Deirdre Le Faye, William Austen-Leigh

However, by 1782, when her daughter Jane was only 7 years old, she was described as having lost several foreteeth, which made her look old.

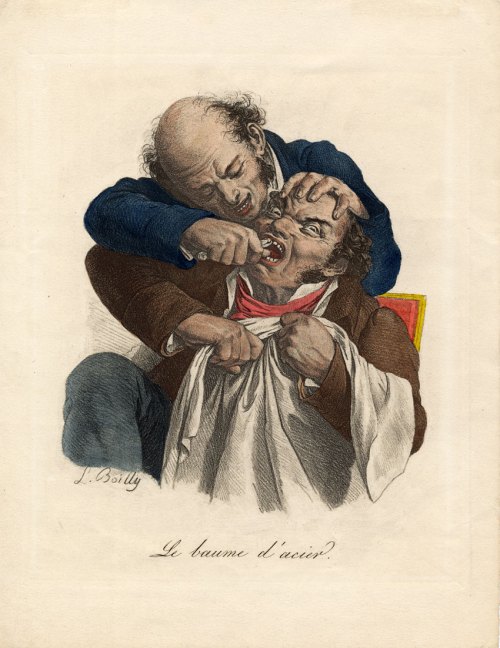

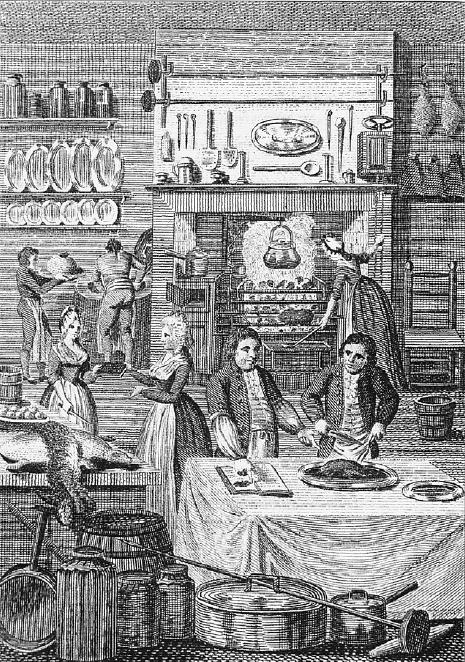

Modern dentistry was still in its infancy when Cassandra Austen gave birth to her eight children. While the wealthy could afford dentists, rural folks still depended on the village blacksmith, who only knew how to pull teeth. Market fairs sold tinctures, toothpowders and abrasive dentifrices.

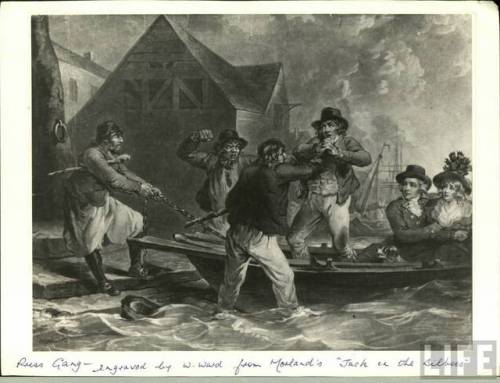

Lucy Baggott, of Wychwood Books, says: ‘It was not uncommon for the local farrier to draw teeth to relieve toothache of those in desperate pain, for then the blacksmith in many rural communities doubled as a tooth drawer. ‘There were many dubious practices adopted: hot coals, string, forceps, and pliers to name a few. Children were lured to sacrifice their teeth for the supposed benefit of the wealthy in exchange for only a few shillings. One print reads: “Most money given for live teeth”. – Dental Quackery Captured in Print

We do know this: tooth extraction was painful and a most unpleasant affair before the age of ether and anesthetics.

In two letters to Cassandra, on Wednesday 15 & Thursday 16 September 1813, Jane [Austen] describes in some detail accompanying her young nieces Lizzy, Marianne and Fanny, on a visit to the London dentist Mr Spence. It was, she relates, ‘a sad business, and cost us many tears’. They attended Mr Spence twice on the Wednesday, and to their consternation had to return on the following day for yet another ‘disagreeable hour’ . Mr Spence remonstrates strongly over Lizzy’s teeth, cleaning and filing them and filling the ‘very sad hole’ between two of the front ones. But it is Marianne who suffers most: she is obliged to have two teeth extracted to make room for others to grow. – The Poor Girls and Their Teeth, A Visit to the Dentist, JASA

Tooth maintenance and dental hygiene were not a new concept. The aristocrats suffered more cavities, for they could afford sweets and foods that would eat into enamel, but they did use tooth powders, tooth picks, and toothbrushes to keep their teeth clean.

The ancient Chinese made toothbrushes with bristles from the necks of cold climate pigs. French dentists were the first Europeans to promote the use of toothbrushes in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. William Addis of Clerkenwald, England, created the first mass-produced toothbrush. Toothpaste: modern toothpastes were developed in the 1800s. In 1824, a dentist named Peabody was the first person to add soap to toothpaste. John Harris first added chalk as an ingredient to toothpaste in the 1850s.- History of Dentistry

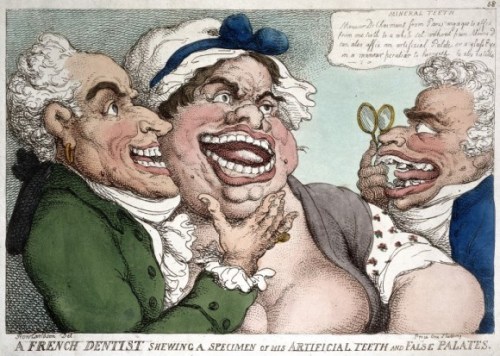

The caption to the above cartoon states: Dentist. 18th century caricature of a fat dentist with his struggling, overweight female patient. The patient is begging the dentist not to pluck her teeth out like he would the feathers of a pigeon. People who eat large amounts of sugary food are often both overweight and suffer from dental decay. Image drawn in 1797 by British artist Isaac Cruikshank (1756-1811). – Science Photo Library

Extractions were by forceps or commonly keys, rather like a door key…When rotated it gripped the tooth tightly. This extracted the tooth – and usually gum and bone with it…Sometimes the jaws were also broken during an extraction by untrained people.”- BBC

A timeline of dentistry in the 18th and 19th centuries:

1780 – William Addis manufactured the first modern toothbrush. 1789 – Frenchman Nicolas Dubois de Chemant receives the first patent for porcelain teeth. 1790 – John Greenwood, one of George Washington’s dentists, constructs the first known dental foot engine. He adapts his mother’s foot treadle spinning wheel to rotate a drill. 1790 – Josiah Flagg, a prominent American dentist, constructs the first chair made specifically for dental patients. To a wooden Windsor chair, Flagg attaches an adjustable headrest, plus an arm extension to hold instruments. 19th Century 1801 – Richard C. Skinner writes the Treatise on the Human Teeth, the first dental book published in America. 1820 – Claudius Ash established his dental manufacturing company in London. 1825 – Samuel Stockton begins commercial manufacture of porcelain teeth. His S.S. White Dental Manufacturing Company establishes and dominates the dental supply market throughout the 19th century. – Nambibian Dental Association

Annotation of the above cartoon by Thomas Rowlandson:

This print is by Thomas Rowlandson (1756-1827) and is dated 1787. It is a satirical comment upon the real practice of rich gentlemen and ladies of the 18th century paying for teeth to be pulled from poor children and transplanted in their gums. The dentist present is portrayed as a quack. There are even two quacking ducks on the placard advertising his fake credentials. He is busy pulling teeth from the mouth of a poor young chimney sweep. Covered in soot and exhausted, he slumps in a chair. Meanwhile the dentist’s assistant transplants a tooth into a fashionably dressed young lady’s mouth. Two children can be seen leaving the room clutching their faces and obviously in pain from having their teeth extracted. As people lost most of their teeth by age 21 due to gum disease, teeth transplants were popular for some time in England although they rarely worked. – Wellcome Images

Thomas Rowlandson – A French dentist showing a specimen of his artificial teeth and false palates Coloured engraving 1811 Image @ Rowlandson, Wellcome Library

Dentures did exist:

Perhaps the most famous false-toothed American was the first president, George Washington. Popular history gave Mr. Washington wooden teeth, though this was not the case. In fact, wooden teeth are impossible; the corrosive effects of saliva would have turned them into mushy pulp before long. As a matter of fact, the first president’s false teeth came from a variety of sources, including teeth extracted from human and animal corpses. – A Short History of Dentistry

As always, the upper classes had the upper hand:

The upper classes could afford a greater range of treatments, including artificial teeth (highly sought after by the sugar- consuming wealthy). Ivory dentures were popular into the 18th century, and were made from natural materials including walrus, elephant or hippopotamus ivory. Human teeth or ‘Waterloo teeth’ -sourced from battlefields or graveyards- were riveted into the base. These ill fitting and uncomfortable ivory dentures were replaced by porcelain dentures, introduced in the 1790’s. These were not successful due to their bright colours, and tendency to crack.Before the 1800’s, the practice of dentistry was still a long way from achieving professional status. This was to change in the 19th century – the most significant period in the history of dentistry to date. By 1800 there were still relatively few ‘dentists’ practicing the profession. By the middle of the 19th century the number of practicing dentists had increased markedly, although there was no legal or professional control to prevent malpractice and incompetence. Pressure for reform of the profession increased. – Thomas Rowlandson, “Transplanting Teeth (c.1790) [Engraving],” in Children and Youth in History, Item #164, http://chnm.gmu.edu/cyh/primary-sources/164 (accessed August 10, 2011). Annotated by Lynda Payne