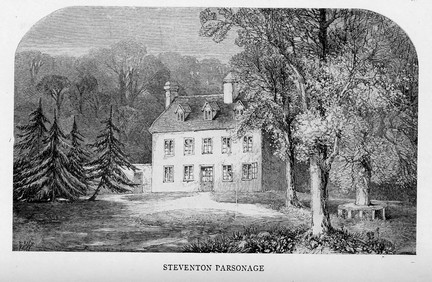

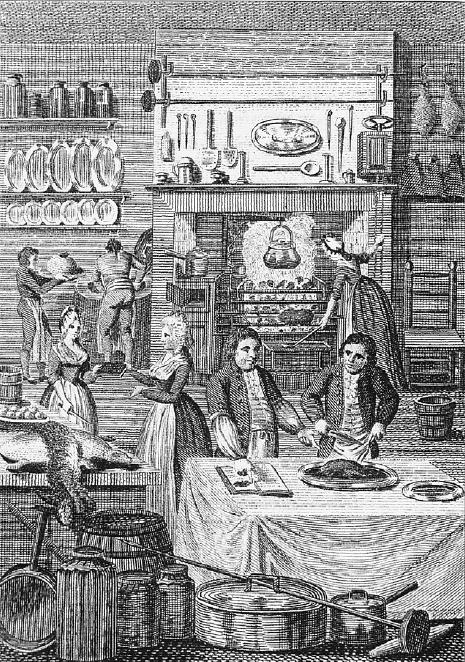

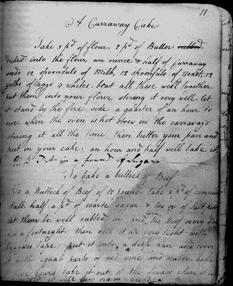

As many Jane Austen fans know, Rev. George Austen ran a boarding school out of his parsonage house in Steventon to augment his £230 pr year income. In1793 he began to teach the sons of local gentlemen in his home to prepare them for university. His library was extensive for a man of modest means, from 300- 500 volumes, depending on the source, an amazing collection, for books were frightfully expensive. Rev. Austen encouraged Cassandra and Jane to read from his library and supported budding author Jane in her writing. At some point, the Austens sent the girls to boarding school in Reading, for which he paid £35 per term, per girl, a not inconsiderable sum. He received around the same amount of money per boarder, and it is conjectured that the Austens hoped to replace their two daughters with many more pupils, which made economic sense. (See Linda Robinson Walker’s link below.) Mrs. Austen was not an indifferent bystander. She cooked, cleaned, sewed, and clucked over the boys like a mother hen, and was involved in their maintenance in a hands-on and caring way, acting as a surrogate mother.

In his Travels Through England in 1782, German traveler Karl Phillip Moritz describes learning academies, head masters, and boarding schools. From his observations, one gains a sense of what life must have been like for the Austens and their pupils:

A few words more respecting pedantry. I have seen the regulation of one seminary of learning, here called an academy. Of these places of education, there is a prodigious number in London, though, notwithstanding their pompous names, they are in reality nothing more than small schools set up by private persons, for children and young people.

One of the Englishmen who were my travelling companions, made me acquainted with a Dr. G– who lives near P–, and keeps an academy for the education of twelve young people, which number is here, as well as at our Mr. Kumpe’s, never exceeded, and the same plan has been adopted and followed by many others, both here and elsewhere.

At the entrance I perceived over the door of the house a large board, and written on it, Dr. G–’s Academy. Dr. G– received me with great courtesy as a foreigner, and shewed me his school-room, which was furnished just in the same manner as the classes in our public schools are, with benches and a professor’s chair or pulpit.

The usher at Dr. G–’s is a young clergyman, who, seated also in a chair or desk, instructs the boys in the Greek and Latin grammars.

Such an under-teacher is called an usher, and by what I can learn, is commonly a tormented being, exactly answering the exquisite description given of him in the “Vicar of Wakefield.” We went in during the hours of attendance, and he was just hearing the boys decline their Latin, which he did in the old jog-trot way; and I own it had an odd sound to my ears, when instead of pronouncing, for example viri veeree I heard them say viri, of the man,exactly according to the English pronunciation, and viro, to the man. The case was just the same afterwards with the Greek.

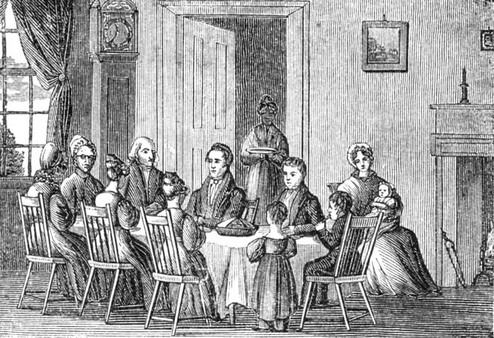

Mr. G– invited us to dinner, when I became acquainted with his wife, a very genteel young woman, whose behaviour to the children was such that she might be said to contribute more to their education than any one else. The children drank nothing but water. For every boarder Dr. G– receives yearly no more than thirty pounds sterling, which however, he complained of as being too little. From forty to fifty pounds is the most that is generally paid in these academies.

I told him of our improvements in the manner of education, and also spoke to him of the apparent great worth of character of his usher. He listened very attentively, but seemed to have thought little himself on this subject. Before and after dinner the Lord’s Prayer was repeated in French, which is done in several places, as if they were eager not to waste without some improvement, even this opportunity also, to practise the French, and thus at once accomplish two points. I afterwards told him my opinion of this species of prayer, which however, he did not take amiss.

After dinner the boys had leave to play in a very small yard, which in most schools or academies, in the city of London, is the ne plus ultra of their playground in their hours of recreation. But Mr. G– has another garden at the end of the town, where he sometimes takes them to walk.

After dinner Mr. G– himself instructed the children in writing, arithmetic, and French, all which seemed to be well taught here, especially writing, in which the young people in England far surpass, I believe, all others. This may perhaps be owing to their having occasion to learn only one sort of letters. As the midsummer holidays were now approaching (at which time the children in all the academies go home for four weeks), everyone was obliged with the utmost care to copy a written model, in order to show it to their parents, because this article is most particularly examined, as everybody can tell what is or is not good writing. The boys knew all the rules of syntax by heart.

All these academies are in general called boarding-schools. Some few retain the old name of schools only, though it is possible that in real merit they may excel the so much-boasted of academies.

It is in general the clergy, who have small incomes, who set up these schools both in town and country, and grown up people who are foreigners, are also admitted here to learn the English language. Mr. G– charged for board, lodging, and instruction in the English, two guineas a-week. He however, who is desirous of perfecting himself in the English, will do better to go some distance into the country, and board himself with any clergyman who takes scholars, where he will hear nothing but English spoken, and may at every opportunity be taught both by young and old.

Source: Moritz, Karl Philipp, 1757-1793. Travels in England in 1782 by Karl Philipp Moritz (Kindle Locations 645-656). Mobipocket (an Amazon.com company).