We’ve arrived at December in Jane Austen’s World, dear readers! We’ve traversed Austen’s life, letters, and novels for a full year now, and it’s been a wonderful adventure.

You can find the rest of the “A Year in Jane Austen’s World” series here: Jan, Feb, Mar, April, May, June, July, Aug, Sept, Oct, and Nov.

Happy Birthday, Jane Austen!

To start, December is Jane Austen’s birthday month, and today, December 16th, is her birthday! Let’s stop for a moment and wish a very Happy Birthday to Jane!!

Can you imagine raising a child like Jane? I’m sure her parents had no idea that their little bundle of joy held such an incredible gift within her – a gift that would bless people around the world for generations to come. Almost 250 years after her birth, people still study and celebrate her writing every day!

December in Hampshire

As we do each month, let us now turn our attention to the lovely Hampshire countryside, the place where Jane spent most of her life, and see what it looks like this time of year. Here are the Chawton Great House gardens in December:

As one might assume, the weather turns cold and brisk this time of year. However, the weather in December did not keep Regency people at home as much as January-March, so many of Austen’s letters and novels feature parties, balls, and gatherings in December. Austen makes mention of December weather in her letters here:

Steventon (26 December 1798):

“The snow came to nothing yesterday, so I did go to Deane, and returned home at nine o’clock at night in the little carriage, and without being very cold.”

Castle Square (27 December 1808):

“We have had snow on the ground here almost a week; it is now going, but Southampton must boast no longer.”

And here is a photo of Jane Austen’s House Museum all decked out for Christmas:

December in Jane Austen’s Letters

We have letters posted from Steventon on December 1st, 18th, 24th, and 28th in 1798; from Castle Square on December 9th and 27th in 1808; and a small mention in January 1809 of an important letter from Charles from posted from Bermuda in December 1808.

But first, perhaps one of the most important letters we have from December – Jane’s father’s letter to his sister announcing his second daughter’s entry into the world!

You have doubtless been for some time in expectation of hearing from Hampshire, and perhaps wondered a little we were in our old age grown such bad reckoners but so it was, for Cassy certainly expected to have been brought to bed a month ago: however last night the time came, and without a great deal of warning, everything was soon happily over. We have now another girl, a present plaything for her sister Cassy and a future companion. She is to be Jenny.

Other odds and ends from Austen’s December letters are below, but I encourage you to read them in their entirety. Her letters are always so newsy and amusing. Several in this batch include information about her brothers away at sea. Relaying letters and news about their whereabouts and safety was of utmost importance to the entire family, as is true of every family with members serving in the military.

Steventon (1 December 1798):

- News of Frank: “I am so good as to write to you again thus speedily, to let you know that I have just heard from Frank (Francis). He was at Cadiz, alive and well, on October 19, and had then very lately received a letter from you, written as long ago as when the ‘London’ was at St. Helen’s… Frank writes in good spirits, but says that our correspondence cannot be so easily carried on in future as it has been, as the communication between Cadiz and Lisbon is less frequent than formerly. You and my mother, therefore, must not alarm yourselves at the long intervals that may divide his letters. I address this advice to you two as being the most tender-hearted of the family.“

- A splendid dinner: “Mr. Lyford…came while we were at dinner, and partook of our elegant entertainment. I was not ashamed at asking him to sit down to table, for we had some pease-soup, a sparerib, and a pudding. He wants my mother to look yellow and to throw out a rash, but she will do neither.”

- New baby and Jane’s opinions on ‘laying in’: “Mary does not manage matters in such a way as to make me want to lay in myself. She is not tidy enough in her appearance; she has no dressing-gown to sit up in; her curtains are all too thin, and things are not in that comfort and style about her which are necessary to make such a situation an enviable one. Elizabeth was really a pretty object with her nice clean cap put on so tidily and her dress so uniformly white and orderly.”

Steventon (18 December 1798):

- A birthday message received: “I am very much obliged to my dear little George for his message,—for his love at least; his duty, I suppose, was only in consequence of some hint of my favorable intentions towards him from his father or mother. I am sincerely rejoiced, however, that I ever was born, since it has been the means of procuring him a dish of tea. Give my best love to him…”

Steventon (24 December 1798):

- News of both brothers in the Navy: “Admiral Gambier, in reply to my father’s application, writes as follows: As it is usual to keep young officers in small vessels, it being most proper on account of their inexperience, and it being also a situation where they are more in the way of learning their duty, your son (Charles) has been continued in the ‘Scorpion;’ but I have mentioned to the Board of Admiralty his wish to be in a frigate, and when a proper opportunity offers and it is judged that he has taken his turn in a small ship, I hope he will be removed. With regard to your son now in the ‘London’ (Francis) I am glad I can give you the assurance that his promotion is likely to take place very soon, as Lord Spencer has been so good as to say he would include him in an arrangement that he proposes making in a short time relative to some promotions in that quarter.”

- One of Jane’s now-famous quotes: “Miss Blackford is agreeable enough. I do not want people to be very agreeable, as it saves me the trouble of liking them a great deal.“

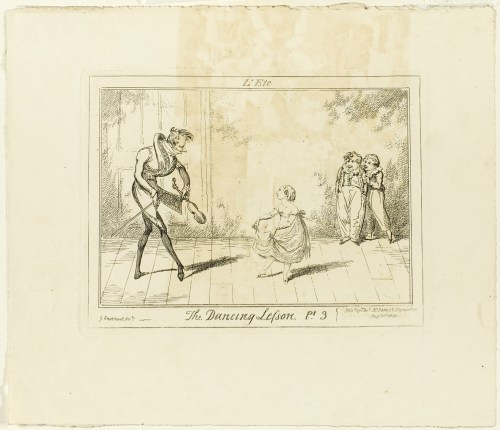

- A Christmas-time ball: “Our ball was very thin, but by no means unpleasant. There were thirty-one people, and only eleven ladies out of the number, and but five single women in the room. Of the gentlemen present you may have some idea from the list of my partners,—Mr. Wood, G. Lefroy, Rice, a Mr. Butcher (belonging to the Temples, a sailor and not of the 11th Light Dragoons), Mr. Temple (not the horrid one of all), Mr. Wm. Orde (cousin to the Kingsclere man), Mr. John Harwood, and Mr. Calland, who appeared as usual with his hat in his hand, and stood every now and then behind Catherine and me to be talked to and abused for not dancing. We teased him, however, into it at last. I was very glad to see him again after so long a separation, and he was altogether rather the genius and flirt of the evening. He inquired after you.”

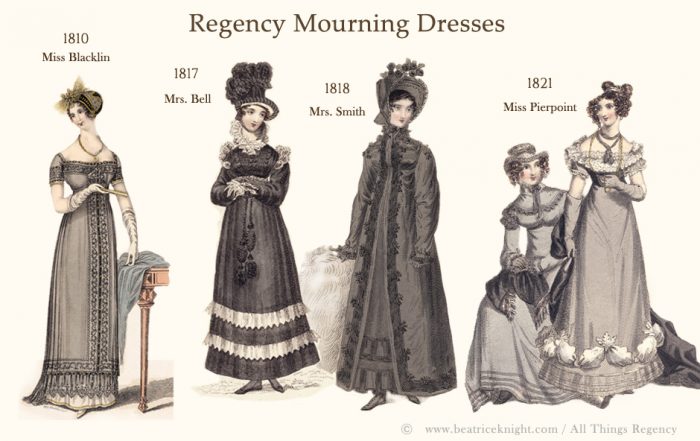

- There were twenty dances, and I danced them all, and without any fatigue. “I was glad to find myself capable of dancing so much, and with so much satisfaction as I did; from my slender enjoyment of the Ashford balls (as assemblies for dancing) I had not thought myself equal to it, but in cold weather and with few couples I fancy I could just as well dance for a week together as for half an hour. My black cap was openly admired by Mrs. Lefroy, and secretly I imagine by everybody else in the room…”

Steventon (28 December 1798):

- More Navy news: “Frank is made. He was yesterday raised to the rank of Commander, and appointed to the ‘Petterel’ sloop, now at Gibraltar. A letter from Daysh has just announced this, and as it is confirmed by a very friendly one from Mr. Mathew to the same effect, transcribing one from Admiral Gambier to the General, we have no reason to suspect the truth of it. As soon as you have cried a little for joy, you may go on, and learn further that the India House have taken Captain Austen’s petition into consideration,—this comes from Daysh,—and likewise that Lieutenant Charles John Austen is removed to the ‘Tamar’ frigate,—this comes from the Admiral. We cannot find out where the ‘Tamar’ is, but I hope we shall now see Charles here at all events.”

Castle Square (8 December 1808):

- A December ball: “Our ball was rather more amusing than I expected. Martha liked it very much, and I did not gape till the last quarter of an hour. It was past nine before we were sent for, and not twelve when we returned. The room was tolerably full, and there were, perhaps, thirty couple of dancers. The melancholy part was to see so many dozen young women standing by without partners, and each of them with two ugly naked shoulders. It was the same room in which we danced fifteen years ago. I thought it all over, and in spite of the shame of being so much older, felt with thankfulness that I was quite as happy now as then. We paid an additional shilling for our tea, which we took as we chose in an adjoining and very comfortable room.”

Castle Square (27 December 1808):

- A new pianoforte: “Yes, yes, we will have a pianoforte, as good a one as can be got for thirty guineas, and I will practise country dances, that we may have some amusement for our nephews and nieces, when we have the pleasure of their company.”

December in Jane Austen’s Novels

There are several mentions in Austen’s novels about Christmas, but as next week’s post from Brenda will focus on Christmas scenes from the novels, we shall mostly stick to the month of December in this article with a few helpful quotes about the Christmas season:

Sense and Sensibility

- Insight on Mr. Willoughby: “He is as good a sort of fellow, I believe, as ever lived,” repeated Sir John. “I remember last Christmas at a little hop at the park, he danced from eight o’clock till four, without once sitting down.”

Pride and Prejudice

- A family holiday: “On the following Monday, Mrs. Bennet had the pleasure of receiving her brother and his wife, who came, as usual, to spend the Christmas at Longbourn.”

Mansfield Park

- A special visit from William: “William determining, soon after her removal, to be a sailor, was invited to spend a week with his sister in Northamptonshire before he went to sea. Their eager affection in meeting, their exquisite delight in being together, their hours of happy mirth, and moments of serious conference, may be imagined; as well as the sanguine views and spirits of the boy even to the last, and the misery of the girl when he left her. Luckily the visit happened in the Christmas holidays, when she could directly look for comfort to her cousin Edmund; and he told her such charming things of what William was to do, and be hereafter, in consequence of his profession, as made her gradually admit that the separation might have some use.”

Emma

- Tolerable weather: “Though now the middle of December, there had yet been no weather to prevent the young ladies from tolerably regular exercise; and on the morrow, Emma had a charitable visit to pay to a poor sick family, who lived a little way out of Highbury.”

- The fogs of December: “The next thing wanted was to get the picture framed; and here were a few difficulties. It must be done directly; it must be done in London; the order must go through the hands of some intelligent person whose taste could be depended on; and Isabella, the usual doer of all commissions, must not be applied to, because it was December, and Mr. Woodhouse could not bear the idea of her stirring out of her house in the fogs of December.”

- Dinner party at Randalls: “The evening before this great event (for it was a very great event that Mr. Woodhouse should dine out, on the 24th of December) had been spent by Harriet at Hartfield, and she had gone home so much indisposed with a cold, that, but for her own earnest wish of being nursed by Mrs. Goddard, Emma could not have allowed her to leave the house.”

Persuasion

- Charles and Mary Musgrove married 16 December, Jane’s birthday: “Sir Walter had improved it by adding, for the information of himself and his family, these words, after the date of Mary’s birth—’Married, December 16, 1810, Charles, son and heir of Charles Musgrove, Esq. of Uppercross, in the county of Somerset…'”

- Mary Musgrove bemoans the lack of December parties: “We have had a very dull Christmas; Mr and Mrs Musgrove have not had one dinner party all the holidays. I do not reckon the Hayters as anybody. The holidays, however, are over at last: I believe no children ever had such long ones. I am sure I had not.”

Northanger Abbey

- A December visit: “Mrs. Thorpe and her daughters had scarcely begun the history of their acquaintance with Mr. James Morland, before she remembered that her eldest brother had lately formed an intimacy with a young man of his own college, of the name of Thorpe; and that he had spent the last week of the Christmas vacation with his family, near London.”

- A long lecture on dress: “Dress is at all times a frivolous distinction, and excessive solicitude about it often destroys its own aim. Catherine knew all this very well; her great aunt had read her a lecture on the subject only the Christmas before…”

December Dates of Importance

And now for our monthly round-up of December dates of importance relating to Jane and her family. This time, there is plenty of family news, plus important publishing news and one very difficult sorrow:

Family News:

- 16 December 1775: Jane Austen born at home in Steventon.

- December 1786: Jane and Cassandra Austen leave Abbey School.

- 23 December 1788: After finishing at the Royal Naval Academy, Francis Austen sails to the East Indies.

- 27 December 1791: Edward Austen marries Elizabeth Bridges.

- 31 December 1797: Henry Austen marries Eliza de Feuillide.

- December 1800: Rev. Austen announces his retirement and intention to move to Bath.

- 2 and 3 December 1802: Harris Bigg-Wither proposes to Austen and she accepts. The next day, she rejects his proposal.

Historic Dates:

- 16 December 1773: An event occurs in the American colonies now known as the Boston Tea Party.

- 2 December 1804: Napoleon crowns himself emperor of France.

Writing:

- December 1815: Emma is published and dedicated to the Prince Regent.

- December 1817: Northanger Abbey and Persuasion published together, posthumously.

Sorrows:

- 16 December 1804: Austen’s close friend, Mrs. Anne Lefroy, is killed in a riding accident.

Looking Forward to Next Year

Writing this series for the past twelve months has been a great joy. I’ve learned a lot, and I feel as though I know and understand Jane Austen and her life and time period better than before. I hope you’ve enjoyed it as well! In the new year, I look forward to a year-long celebration of the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen’s birth and all the events and books coming our way. Have a very happy Christmas!

RACHEL DODGE teaches college English classes, speaks at libraries, teas, and conferences, and writes for Jane Austen’s World blog. She is the bestselling, award-winning author of The Anne of Green Gables Devotional, The Little Women Devotional, and Praying with Jane: 31 Days Through the Prayers of Jane Austen. Her most recent book is The Secret Garden Devotional. A true kindred spirit at heart, Rachel loves books, bonnets, and ballgowns. Visit her online at www.RachelDodge.com.