As a blogger who is curious about all things in Jane Austen’s world and customs in her past that might have influenced her, I am still amazed at how one tiny clue points to another until I land on a series of sites that open up a whole new topic. While history foodies probably know about the elaborate lengths that pastry chefs took to please their patrons, the visual results of a full banquet are simply astounding. I can only assume that Georgian taste buds were equally pleased.

Modern chef and historian, Ivan Day, recreated a feast from the past using sugar structures and porcelain figures to arrange a fanciful garden centerpieces for the table.

I already knew about The Prince Regent’s elaborate 1811 dinner at Carlton House, which was described as thus:

“Along the centre of the table about six inches above the surface, a canal of pure water continued flowing from a silver fountain beautifully constructed at the head of the table. Its banks were covered with green moss aquatic flowers; gold and silver fish swam and sported through the bubbling current, which produced a pleasing murmur where it fell, and formed a cascade at the outlet.” – The Gentleman’s Magazine, describing the Prince Regent’s fete at Carlton House, June 19, 1811 in honor of the exiled French royal family.

The great kitchen at the Prince Regent’s Pavilion at Brighton could accommodate creating dishes for huge and fanciful banquets.

So great was the interest that the doors of Carlton House were opened for three days in a row. But instead of satisfying the curiosity of the masses, the result was ever-increasing crowds. Chaos ensued.

‘The condescension of the Prince in extending the permission to view the arrangements for the late fete at Carlton House has nearly been attended with fatal consequences,’ reported one newspaper. Read more: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1039063/As-Queen-opens-Palace-Ballroom-public-story-decadent-royal-banquet-ever.html#ixzz1s7ijkAEv

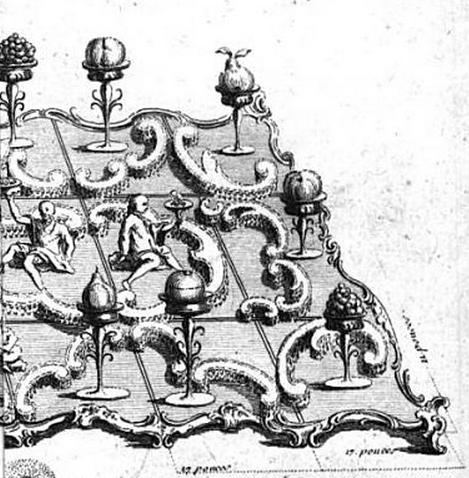

Detail of the design for an elaborate garden centerpiece. These engravings were showcased in Le Cannameliste Français by famed confectionary chef, Joseph Gilliers, in the mid-18th century. View the entire centerpiece here: Click on this link.

The banquet featured a recreation of a landscape at its center. Such a method of decorating a table was not new, especially when it came to desserts. Elaborate set pieces with architectural French influence were created for tables using spun sugar and Sevres bisque figures to create fantasy landscapes. Before the Napoleonic Wars, travel over the English Channel between British and French courtiers and diplomats was common, and thus the French chef’s custom of creating these elaborate centerpieces became well-known in England. Upper class households vied for highly paid (and desired) French chefs, and by the 1820s these gentlemen had by and large invaded British upper class kitchens. Their ability to create dishes that feasted both the eyes and the stomach was unrivaled.

This was an era when confectionary was considered as much a branch of the decorative arts as of cuisine, and porcelain for the table represented prestige as well as a demonstration of power. The combination of French chef, porcelain, and fanciful confectionary desserts served as symbols of prestige and wealth, for no ordinary household could offer such an extravagant display of food and panoply. (View this porcelain table centerpiece set.)

Most of the images of the banquets and figurines are copyrighted. I encourage you to click on the links to view the spectacular results of sugar and porcelain table centerpieces that mimic gardens, sculptures, and figures based on famous paintings. The fanciful recreation included redesigning tables as well.

Amy Hauft, VCU sculpture department. Confectioner Joseph Gilliers conceived his 100-seat rococo fantasy for the serving of a single course — dessert — in a garden setting. The centerpiece atop the tailored white tablecloth was to be a sculpture made of sugar paste fortified with dried sturgeon bladder. There is no record that this table was ever built by Gilliers. Image@Richmond Times Dispatch

More on this fascinating topic:

- Ivan Day, who oversees the Historic Food website and Food History Jottings blogs, is a modern-day chef who recreates sumptuous food from the past. His post on Edible Artistry is to die for.

- Le Cannameliste Francais, Joseph Gilliers, 1768

- Sugar Sculpture, Porcelain and Table Layout 1530-1830, Howard Coutts and Ivan Day

- A Feast for the Eyes

- Regency Excess At Atthingham

- Just Desserts.

- Eye Candy: The Magazine Antiques

- Ivan Day: Regency Dining

- At Table: High Style in the 18th Century

- A Scene of Sugar Fit for a Table of Yore

- The Great Kitchen at the Brighton Pavilion

- Metropolitan Museum: LeCannameliste Français, Ou Nouvelle Instruction Pour Ceux Qui Desirent D’Apprendre L’Office, Rédigé en Forme de Dictionnaire, Written by Joseph Gilliers (French, died 1758)

- Bisque lions

- Banquet Coronation of George IV, Culture 24, Parliament Week

- Sweet Structures: Art & Architecture Made of Sugar

- Sweet Invention, A History of Dessert, Michael Krondl

- Click here to view a painting by Luke Clennell of a banquet in honor of the Prince Regent.

- Carpe Diem!

- Recreating a rococo fantasy

- Click here to see more of Gilliers’ illustrations.