There is an old 18th century white washed house in The High Street of Kingston upon Thames that backs on to the river. On the road side there is a large circular green plaque positioned on the outside wall of this house that reads:

There is an old 18th century white washed house in The High Street of Kingston upon Thames that backs on to the river. On the road side there is a large circular green plaque positioned on the outside wall of this house that reads:

“ Cesar Picton

c1755-1836.

A native of Senegal

West Coast of Africa.

Brought to England in 1761

as servant to Sir John Philips of Norbiton

Kingston upon Thames.

Later a coal merchant and gentleman.

Lived here 1788 – 1807.”

Cesar Picton's house, front. Image @Tony Grant

Cesar Picton was a slave in the ownership of Sir John Philips, and was made a freed man. It is interesting to note that 1807, the last year Cesar Picton lived in this house, before he moved to Thames Ditton, a few miles away, the year the slave trade was abolished in Britain. It would be another twenty-six years before slavery itself would be abolished.

The road outside Cesar Picton's house. Image @Tony Grant

Cesar Picton

But Cesar Picton was a freed man long before this event and already a prosperous merchant. His freedom had to do with Sir John Philips and what he and his family believed. Jane Austen would have passed through Kingston at the time Cesar Picton was a gentleman and merchant there. I wonder if she saw him in the streets? Jane’s family must have had close connections with slavery. Her brother Henry was a banker. Most of the wealth of Britain at the time came from slavery. Her brother Charles was a Royal Naval captain and was stationed on the North American station, often calling into Bermuda. His ship must have been used to protect the slaving ships that the fictional SirThomas Bertram, in Mansfield Park, relied on for his wealth in the plantations.

Slave ship, Bristol

Apart from this oblique reference in Mansfield Park, Jane never mentions slavery or her views about it. During her lifetime the slave trade was abolished but not slavery itself. But change was happening, and by the time Cassandra died slavery was seen as a repugnant thing and was abolished. Was it one of the reasons Jane’s letters were culled by Cassandra in later life? Did she try to hide Jane’s – perhaps – unpopular views in the tide of anti slavery? We will never know.

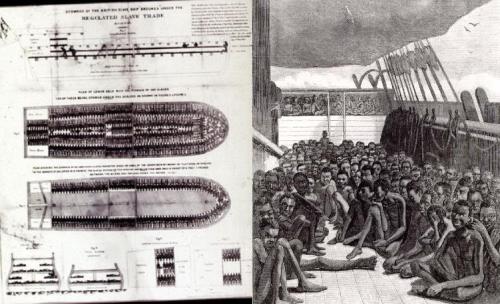

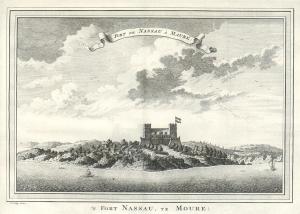

The year 1761, when Cesar Picton was brought to Britain by Captain Parr of the British Army especially for Sir John Phillips, is an interesting one. Senegal had been British up to 1677, when the French took it over. France and Britain had been at war in the late18th and early 19th centuries. Goree, the island just off Senegal that was used for trading slaves, changed hands briefly during these wars back and forth between the British and French. It could well have been during one of these brief spells in charge by the British that Cesar Picton was bought as a promising servant for a wealthy man back in England.

There must have always been an element in British religious and moral sensibilities that saw these African slaves as equal human beings and at a high government level. In 1788 Britain set up a settlement for freed slaves further along the coast from Senegal to accommodate slaves from the plantations of Virginia and Carolina. They had helped the British fight The War of Independence against the Americans, and a place for them to live had to be found after the British retreated from America. Nova Scotia was their first settlement, but the climate was too cold.

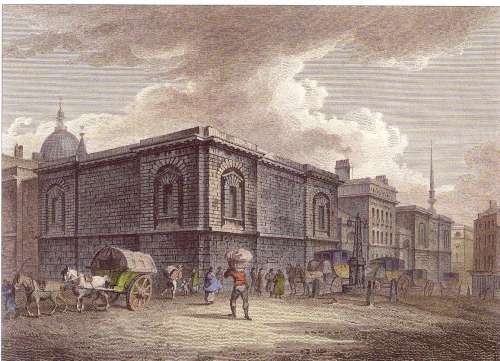

Freetown, Sierra Leone, 1803

Sierra Leone on the West African coast was set up for them, and Freetown, the capital, was established. But slavery was a vital element in the Empire for trade and financial wealth. It couldn’t be given up that easily, no matter how much it pricked certain people’s consciences, and the majority of people in England were kept ignorant of what went on in the slave plantations.

Sir John Philipps

Sir John Philipps (1666 – 1773), the gentleman who obtained Cesar Picton, was a member of an illustrious family whose main seat was Picton Castle, near Haverfordwest in Pembrokeshire, South Wales. In the 18th century, the Philips family was the most powerful family in the political, social, and economic arenas in Pembrokeshire. Sir John Philips, who owned large areas of land in Wales, was a philanthropist who supported the building of schools. He built twentythree of them in Pembrokeshire alone. He also built schools in Camarthenshire.

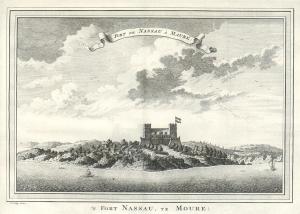

Fort Nassau, Senegal, 1760

It was to Picton Castle in Wales that Cesar Picton was first brought from Senegal. He then took the name of the castle as his surname.

Picton Castle, Pembrokeshire, 1865

Sir John Philipps attended Westminster public school in 1679 when he was 13 years of age. He went on to Trinity College, Cambridge between 1662 to 1664, and was admitted to Lincolns Inn in 1683. He did not complete his degree at Cambridge, and he was not called to the bar either. Sir John appears to have wasted his time and seemed to have enjoyed a frivolous life style when he was young. However by 1695 he became the Member of Parliament for Pembrokeshire. He remained a Member of Parliament until 1702. He then later returned to parliament for Haverfordwest and remained there until 1772. On the 18th January, 1697, Sir John’s father died, and he became the 4th baronet. In the same year he married Mary, the daughter and heiress of Anthony Smith, a rich East India merchant. Sir John had influential friends and great wealth. His sister Elizabeth’s daughter married Horace Walpole in 1700.

The Oxford Holy Club

From 1695 to 1737, Sir John was a leading figure in many religious and philanthropic movements. Most important of all, in relation to Cesar Picton, Sir John was a member of The Holy Club. The Holy Club had many religious reformers amongst its numbers, A.H. Francke, A.W. Boehme, J.F. Osterwald, John and Charles Wesley and George Whitefield. These were Evangelists, Methodists and Quakers. It was from amongst these religious colleagues that the anti slavery movement found it’s strength and became an unstoppable force. Sir John was part of a group therefore that constructed the legislation to abolish the save trade and eventually abolish slavery. In his treatment of Cesar Picton we can see these beliefs in early action. It might have been that Sir John Picton actively sought a slave from Senegal with the express purpose of freeing him once back in England and supporting him to become a wealthy esteemed member of society. Maybe Cesar Picton was his proof that slaves were his equal. This is what happened to Cesar Picton.

Cesar Picton's coal wharf site. Image @Tony Grant

Cesar Picton was six years old when he was brought to England by Captain Parr , an British Army officer who had been serving in Senegal.. He was given to Sir John Philips along with a parakeet. Cesar was born a Muslim but soon after arriving in Sir John’s household at Picton Castle he was baptised and given the name of Cesar on the 6th December 1761. He was dressed as a servant wearing a velvet turban, which cost 10 shillings and sixpence. It was fashionable for black servants to be richly dressed. There were very few black servants in England. Only very rich merchants and the wealthy aristocracy would have them. They were not treated the same as slaves which were used in their tens of thousands on the sugar, tobacco and cotton plantations of the West Indies and the mainland coast of America. Normally a black servant would have been the personal servant of the male head of the household but Cesar became the favourite of Lady Philips. He mixed with the family on equal terms. Sir John’s philanthropic and religious beliefs were applied to the treatment of Cesar.

Horace Walpole

Horace Walpole, the younger son of the first British Prime Minister Robert Walpole. who married Elizabeth the sister of Sir John, wrote in a letter to a friend in 1788,

“I was in Kingston with the sisters of Lady Milford; they have a favourite black, who has been with them a great many years and is remarkably sensible.”

Sir John died in 1764 and his son became Lord Milford. Milford is the area in Wales where Picton Castle is situated. Lady Milford made a new will in which she left Cesar £100. Her son sold Norbiton Place near Kingston. With the money he was given, Cesar was able to rent a coach house and stables next to the Thames in Kingston. This building today is called Picton House.

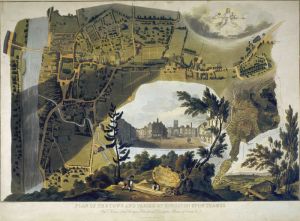

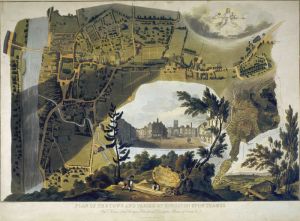

Kingston Upon Thames, 18th century

After paying a corporation tax of £10 to trade, Picton set himself up as a coal merchant. By 1795 he had made enough money to buy Picton House, a wharf for his coal barges, and a malt house for brewing beer. In 1801, one of the Philips daughters died and left him a further £100. He was wealthy by now on his own terms. In 1807,when he was 52, he let his properties in Kingston and lived in Tolworth neaby to Kingston for a while.

Picton House, Thames Ditton

In February 1816 he bought a house in Thames Ditton, down river from Kingston, for the then massive sum of £4000. He lived there for the next twenty years until his death. When he died the list of the contents of his house included a horse and chaise, two watches, with gold chains, seals, brooches, gold rings, a tortoiseshell tea chest, silver spoons and tongs. There were also paintings of his friends hanging in his house including a portrait of himself.

While Picton was living in Thames Ditton, the other two Philips daughters died in Hampton Court. Joyce left him £100 and Katherine left him £50 and a legacy of £30 per year for life. Cesar himself died in 1836 aged 81. He did not marry and had no heirs, and was buried in All Saints Church, Kingston upon Thames on the 16th June, 1836. He had become very fat in his old age and his body had to be taken to the church on a four-wheeled trolley.

Cesar Picton Gravestone. Image @Find a Grave

Unlike some of the other freed slaves in England at the time, Cesar did not make his thoughts known about slavery and the slave trade. He was happy to lead a comfortable life. Olaudah Equiano wrote a book about his experiences and actively took part in the campaigning of William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson. Others, like Briton Hammon and Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, made oral accounts that were transcribed. Letters were written by Ignatius Sancho to help bolster the anti slavery cause.

Jane Austen wrote in Mansfield Park,

These opinions had been hardly canvassed a year, before another event arose of such importance in the family, as might fairly claim some place in the thoughts and conversation of the ladies. Sir Thomas had found it expedient to go to Antigua himself, for the better arrangement of his affairs, and he took his eldest son with him in the hope of detaching him from some bad connections at home. They left England with the probability of being nearly a twelve month absent.”

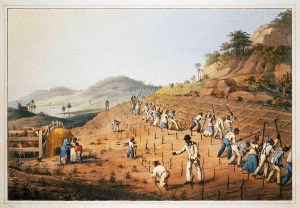

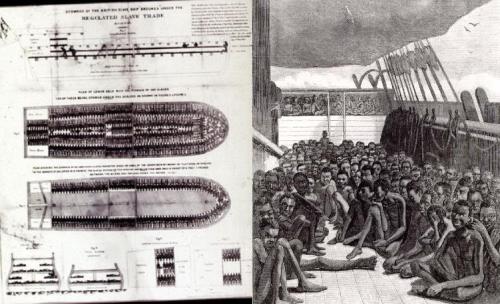

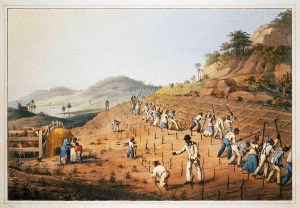

Slaves digging the cane holes, Antiqua, 1823

Sir Thomas Bertram’s affairs in Antigua could only have referred to his sugar plantations, the source of all his wealth and the financial source of Mansfield Park itself.

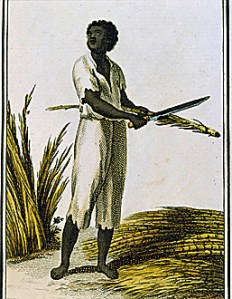

Slave cutting sugar cane, 1799

Jane’s own brothers, Frank and Charles would have been amongst the captains with their warships used to protect the likes of Sir Thomas Bertram’s trading ventures, which must have included slaves for his plantations in Antigua. Henry, Jane’s favorite brother, would have invested the proceeds of this trade through his bank. It is very possible that Jane caught sight of the famous Cesar Picton, wealthy merchant and freed man, walking in the streets of Kingston upon Thames. I wonder what her opinion was?

Kingston Upon Thames, Thomas Hornor, 1813

Post written by Tony Grant, London Calling.

More on the topic:

Read Full Post »