One of the most pivotal decisions in Pride and Prejudice was when Elizabeth Bennet agreed to visit Pemberley’s gardens and grounds with the Gardiners, only to suddenly encounter Mr. Darcy, who was not slated to return until the next day.

Such a visit to grand estates by the well-heeled and more common folk like Elizabeth and her aunt and uncle were quite common in the 18th century. They would have purchased an inexpensive guide book at a local inn or town, and read information about the paintings and objects inside the great houses, and a description of the gardens and their rustic buildings and ornaments.

Stowe in particular was a destination point for visitors. Its magnificent gardens and grounds were a model and inspiration for other gardens of the Romantic era, which echoed the movement’s reverence for nature and aesthetic ideals. The blog of the current Duke of Buckingham and Chandos contains this passage:

“The house and gardens at Stowe, my family seat, were tourist attractions from around 1724, when my ancestor Lord Cobham set out the gardens. People came to visit the gardens and house, sometimes invited, often not. Topographical notes and poems were written. And in 1744 the first full guidebook to the house and grounds was published by Benton Seeley, a writing master in Buckingham. The guidebooks continued for a further 70 years and Seeley went on to become a printer and publisher, founding a business that wound up only in 1978.” – Duke of Buckingham and Chandos

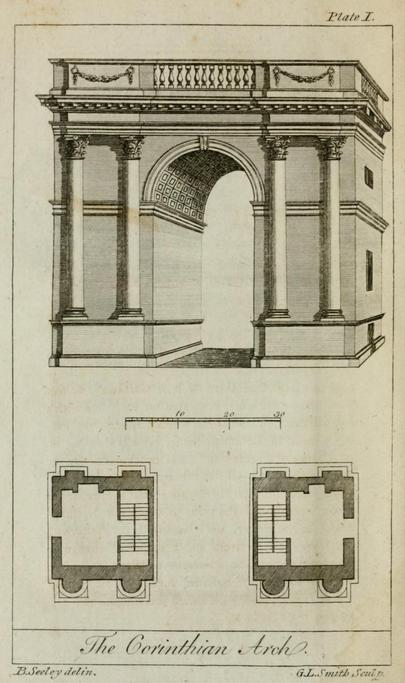

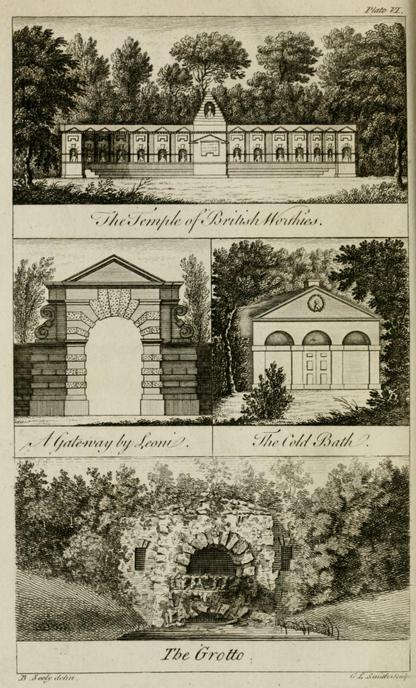

Benton Seeley’s guidebook, Stowe: A Description of the Magnificent House and Gardens of The Right Honourable Richard Grenville Temple, Earl Temple… Embellished with a General Plan of the Gardens, and also a separate Plan of each Building, with Perspective Views of the same, was published in the same year that Elizabeth Montague described Stowe’s gardens as “beyond description, it gives the best idea of Paradise that can be.” Visitors came away from viewing Stowe’s natural gardens inspired to implement changes to their own grounds. Seeley’s guidebook helped to spread Stowe’s influence throughout the 18th century as the model for the ideal English garden. (Today the original guidebook sells for close to $2,000.)

Thomas Jefferson owned at least two of Seeley’s guidebooks. In fact, Stowe’s reputation as a gardening attraction had spread beyond the British Isles:

“When well-heeled Americans traveled to England in the late eighteenth century, they often sought out famous gardens to inspire their own designs at home. As Benton Seeley’s Stowe: A Description of the Magnificent House and Gardens shows, the gardens at Stowe were particularly large and ornate, featuring temples, pavilions, and statues strewn about the grounds. Thomas Jefferson and John Adams visited Stowe together in 1786 in what Abigail Adams called their “journey into the country.”- Better Homes and Gardens, Stanford University

Seeley’s Guide Book became historically significant. It went through seventeen editions between 1744 and 1797, continually undergoing improvements and revisions. The book’s influence was such that it helped to make the Stowe gardens among the most publicized and copied of the English landscape model. However, Seeley’s was not the only guidebook written for the famed Stowe gardens. In 1732 Lord Cobham’s nephew Gilbert West wrote a lengthy poem The Gardens of the Right Honourable Richard Viscount Cobham that is actually a guide to the gardens in verse form. Charles Bridgeman commissioned 15 engravings of the gardens from Jacques Rigaud, and these were published in 1739 (Wikipedia), five years before Seeley’s guide.

The Stowe gardens and grounds were extensive, offering planned vistas along a winding path, parterres, canals, large swaths of meadows, places for isolation and retreat, rustic buildings, and an emphasis on natural grandeur over formal symmetry. The 4th Baronet, Viscount Cobham, who married a rich brewery heiress, implemented the garden changes at Stowe in 1711. By 1724, the gardens rested on 24 acres and required the labor of 30 men. Garden maintenance cost the family 827 pounds in 1749-1750. Multiply that amount by 50, and you gain a quick idea of the cost in today’s terms. This sum represented almost all the spare money Lord Cobham could afford on the house and grounds.

The grotto was originally designed by William Kent in the late 1730s as a symmetrical, freestanding structure decorated with flints, colored glass, and shells. Soon covered over with earth, it was then described as a “romantic retirement.” By the 1780s, it was more deeply buried, resurfaced with tufa, and planted with vines and conifers for a cavernous effect.- Romantic Gardens: Nature, Art, and Landscape Design, 2010, The Morgan Library Museum

In “A fine house richly furnished: pemberley and the visiting of country houses,” Stephen Clarke, a London lawyer and architectural historian discusses the kind of information a guidebook owner could expect. A New Description of Blenheim by Mayor, 1811, offered the following General Information in its preface:

“BLENHEIM may be seen every afternoon, from three till five o’Clock, except on Sundays and public Days. On Fair days at Woodstock, likewise, it can be seen only by particular permission.

COMPANY who arrive in the morning may take the ride of the Park, or the walk of the Gardens, before dinner, and after that visit the Palace.

The CHINA GALLERY, PARK, and GARDENS, will, on proper application, be shewn at any hour of the day, except during the time of Divine Service on Sundays.”

In 1776, the Wilton visitors book showed 2, 324 visitors in the last year.

As discussed on this blog in another post, The Housekeeper as a Guide to a Great Country Estate, housekeepers and other servants stood to make a great deal of extra money from tourists.

“The rapacity of housekeepers-and, in the larger houses, of the other staff–was a common complaint. At Blenheim during his tour of 1810-1811, Louis Simond was required to pay the porter at the gate, the woman showing the china collection, the woman showing the theatre, the woman showing the pleasure grounds, the gardener showing the park, and the upper servant showing the house–at a total cost of 19s. (qtd. in Ousby 81). There are similar complaints of Woburn, Chatsworth, and other great houses. Horace Walpole wryly remarked that he should have married his own housekeeper, who had grown rich on showing Strawberry Hill, as the only way of recouping some of his expense on the house (Walpole Correspondence 33, 411) –

At most houses, the traveller would send in his name to the porter or housekeeper to request access–at Hagley in 1800 Mrs. Lybbe Powys, (5) a perceptive visitor of country houses, noted that “we sent in our names for leave to walk round Lord Curzon’s [actually Lord Lyttelton’s] grounds, and he desired we would go into any part of it we chose, without being attended by his gardener” (Lybbe Powys 339). Elizabeth and the Gardiners were of course accompanied by the gardener in the park at Pemberley, as was normal. – A fine house richly furnished: pemberley and the visiting of country houses, Stephen Clarke

In the YouTube video below, one can get a sense of Stowe’s grounds and gardens in the first 3 ½ minutes. Enjoy the tour!

More on the topic:

- Stowe’s Legacy, Treasure Hunt

- The Octagon Lake Cascade, Stowe

- Peter Hayden, Reviewed work(s):Temples of Delight: Stowe Landscape Gardens by John Martin Robinson, Descriptions of Lord Cobham’s Gardens at Stowe 1700-1750 by G. B. Clarke; Lord Cobham, Garden History, Vol. 19, No. 1 (Spring, 1991), pp. 100-102, (review consists of 3 pages)Published by: The Garden History Society. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1586995

- The rise and fall of the Grenvilles: dukes of Buckingham and Chandos, 1710 to 1921, p22 J.V. Beckett, Manchester University Press ND, 1994 – Architecture – 308 pages, ISBN 0719037573, 9780719037573

- Viscount Cobham

- Archive for Stowe: National Trust Collections