“Memorandums for the use [of] Mr. F. W. Austen on his going to the East Indies Mids[hip]man on board his Majesty’s Ship Perseverance Cap: [Sm]ith Decr. 1788”

Thus begins a letter from Jane Austen’s father to her older brother Francis. Francis, who Jane called Frank, went to sea at age 14. He had been at the Royal Naval Academy in Portsmouth (home town of Fanny Price of Mansfield Park) for two and a half years.

Lieutenant Francis Austen, 1796, about eight years after his father sent this letter

Their father had written to Francis regularly at school. He now felt that his son needed to know more about subjects “of the greatest importance”—his relationships with God and with people.

Francis apparently treasured this letter. There is even fire damage on some of the folds, since he had it with him on shipboard. It was found among his papers when he died at age 91.

His descendants quoted much of the letter in the book Jane Austen’s Sailor Brothers. However, they did not quote the second paragraph. Instead they summarized it as “some well-chosen and impressive injunctions on the subject of his [George Austen’s] son’s religious duties.” (They also left out a few later parts of the letter, such as George telling his son to keep himself clean and take care of his teeth!) We can learn a lot about the Austen family’s religious beliefs and practices from the missing second paragraph.

The “Memorandums”

At the end of the first paragraph, George Austen says his son’s own “good sense & natural Judgment of what is right” will guide him in specific circumstances. Then he writes with more general advice:

“The first & most important of all considerations to a human Being is Religion, or the belief of a God & our consequent duty to him, our Neighbour, & ourselves – In each of these your Catechism instructs you, & for what is further necessary to be known on this subject in general, & on Christianity in particular I must refer you to that part of the Elegant Extracts where you have Passages from approved Authors sufficient to inform you in every requisite for your belief & practice. To these I refer you & recommend them to your frequent & attentive perusal; observing only on this head, that as you must be well convinced how wholly you depend on God for success in all your undertakings, you will easily see that you are bound in interest as well as duty regularly to address yourself to him in Prayer, Night & Morning; thankfully acknowledging the Blessings you have received already & humbly beseeching his future favor & protection. Now this is a Duty which nothing can excus[e t]he omission of times of the greatest hurry will not hinder a well dis[pose]d mind from fulfilling it – for a short Ejaculation to the Almig[ht]y, when it comes from the heart will be as acceptable to him as the most elegant & studied form of Words.” (The parts in [brackets] are damaged areas of the letter.)

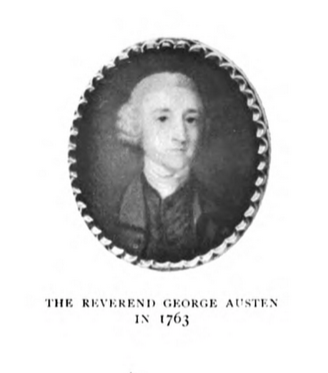

Reverend George Austen, rector of Steventon and Deane

Jane and Francis Austen grew up in a very religious household. Their father was a clergyman, a priest in the Church of England. Some clergymen at this time saw their job simply as a source of income, and did the minimum they could. In Mansfield Park, Henry Crawford assumes that Edmund Bertram will be such a clergyman. But Edmund is determined to live among his people and set a good example for them—as George Austen actually did in his parish.

Religious Duties and the Catechism

Reverend Austen begins by telling his son that religion is the most important thing in life. Jane Austen echoes this belief in Mansfield Park. Edmund says that the clergy “has the charge of all that is of the first importance to mankind, individually or collectively considered, temporally and eternally . . . the guardianship of religion and morals, and consequently of the manners which result from their influence.” (Italics added.) Religion meant religious practices and teachings; morals (which Austen also called “good principles”) were inward knowledge of right and wrong, based on religion; and manners were outward actions towards other people (not just politeness).

Rev. Austen similarly defines religion as “the belief of a God & our consequent duty to him, our Neighbour, & ourselves.” In other words, religion includes both what people believe and how they act based on their beliefs.

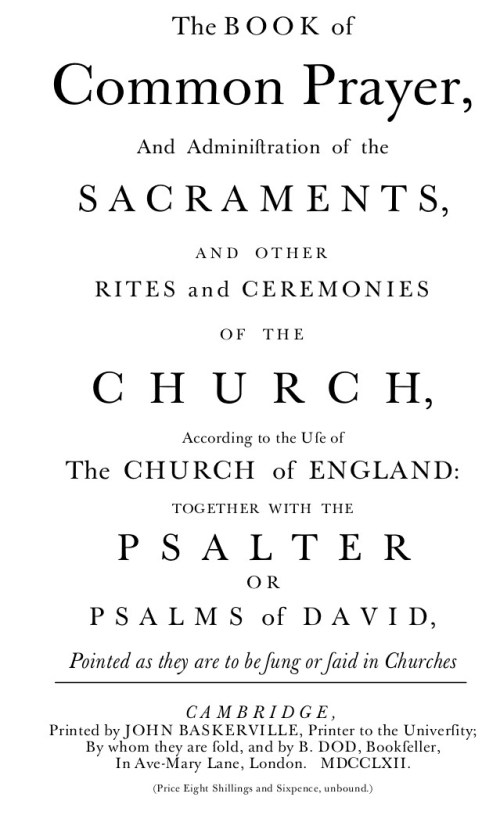

He says the Catechism teaches these duties. Frank and Jane would have memorized the Catechism from the Church of England’s Book of Common Prayer. In it, the child recites the Ten Commandments, which teach a person’s duty towards God and towards their neighbour.

The Book of Common Prayer, 1762, which includes the Catechism that George Austen refers to

When the child is asked what his duty is toward God, he responds,

“My duty towards God, is to believe in him, to fear him, and to love him with all my heart, with all my mind, with all my soul, and with all my strength; to worship him, to give him thanks, to put my whole trust in him, to call upon him, to honour his holy Name and his Word, and to serve him truly all the days of my life.” (This is considered to be a summary of the first four of the Ten Commandments.)

The child is then asked what his duty is toward his neighbour. He answers,

“My duty towards my Neighbour, is to love him as myself, and to do to all men, as I would they should do unto me: To love, honour, and succour my father and mother: To honour and obey the King, and all that are put in authority under him: To submit myself to all my governors, teachers, spiritual pastors, and masters: To order myself lowly and reverently to all my betters: To hurt no body by word or deed: To be true and just in all my dealings: To bear no malice nor hatred in my heart: To keep my hands from picking and stealing, and my tongue from evil-speaking, lying, and slandering: To keep my body in temperance, soberness, and chastity: Not to covet, nor desire other men’s goods; but to learn and labour truly to get mine own living, and to do my duty in that state of life, unto which it shall please God to call me.” (This section is based on the last six of the Ten Commandments.)

Jane Austen refers to some of these duties in Sense and Sensibility. When Marianne Dashwood repents of her failures, she says, “Whenever I looked towards the past, I saw some duty neglected, or some failing indulged.” She has failed in her duties to love her neighbour as herself and “to hurt no body by word or deed,” as the Catechism says.

The Catechism refers to one’s “betters” and one’s “state of life.” In Austen’s England, each person was believed to have a specific God-ordained place in society. George Austen later advises his son on the “three Orders of Men” he will encounter: his superior officers, his “Equals,” and his “Inferiors.” He recommends treating them with respect and kindness.

The Catechism doesn’t specifically address our duty “to ourselves,” as George Austen says. However, it does say “To keep my body in temperance, soberness, and chastity.” That means to care for oneself by not eating or drinking too much or indulging in sex outside of marriage. Later in the letter Rev. Austen says that Frank already knows that soberness is important for his health, morals, and fortune.

George Austen probably thought that doing our duty to God and to man would also be a way of doing our duty to ourselves. The Austens were familiar with Thomas Secker’s Lectures on the Catechism. The introductory lecture states that “the happiness of all Persons depends beyond Comparison chiefly on being truly religious.” Rev. Austen also points out that if Frank treats others well it will add to his “present happiness & comfort” as well as his “future well-doing.”

Elegant Extracts

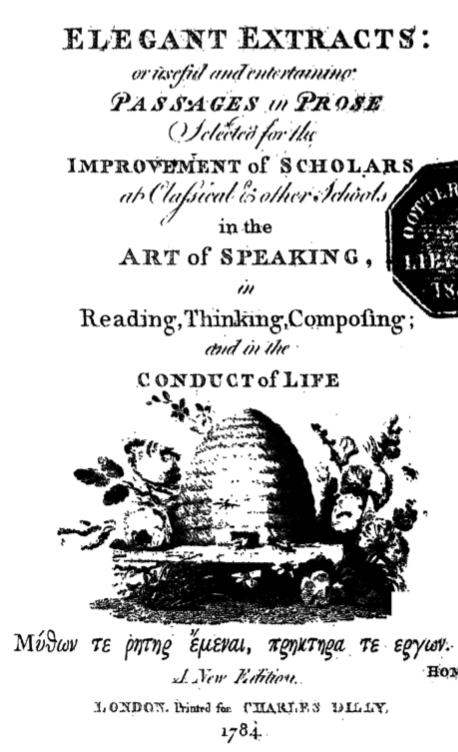

Rev. Austen told his son to read Elegant Extracts frequently and attentively. It contained “approved Authors sufficient to inform you in every requisite for your belief & practice.” Elegant Extracts was a large schoolbook with a wide variety of selections from books and essays. The first section contained 135 “Moral and Religious” writings (in the second edition, 1784). More than 40 were from sermons by Hugh Blair.

Elegant Extracts: This 1784 edition is probably the one Francis Austen owned.

Hugh Blair was a Scottish Presbyterian minister whose books of sermons were very popular. Jane Austen enjoyed reading sermons, as many people did in that time. Clergymen often read other men’s sermons from the pulpit. In Mansfield Park, Mary Crawford says a preacher should have the sense to preach from Blair’s Sermons rather than writing his own. (Blair also wrote a book on rhetoric which is mentioned in Northanger Abbey. It is quoted extensively in the introduction to Elegant Extracts.)

Blair’s first entry in Elegant Extracts emphasizes that those in any “station of life” who work hard and do right will prosper. However, those who seek only their own amusement will end up miserable. Other extracts address topics like contentment and cheerfulness. In his letter, George Austen also stresses these themes.

It seems surprising that Rev. Austen recommended Elegant Extracts for religious instruction rather than the Bible. However, some Christian groups in Austen’s time interpreted the Bible in ways that did not fit the Austens’ orthodox Anglican faith. Therefore he may have preferred that Frank read “approved” interpretations. Or perhaps he thought his 14-year-old son might more easily understand Elegant Extracts, which was intended for schoolboys.

Prayer

Finally, George Austen gives Frank specific instructions on prayer.

- Why should Frank pray? Because he depends completely on God for any success in whatever he does; he needs God’s help. The Catechism also says that people need God’s grace to keep his commandments. It gives the Lord’s Prayer as a way to ask for that help.

- When should he pray? Every night and morning, even in “times of the greatest hurry.” The Church of England follows a liturgy. Sets of prayers are read each day, along with Bible readings that change throughout the year. Austen’s family probably read “Morning Prayer” and “Evening Prayer” together daily from The Book of Common Prayer. These also include the Lord’s Prayer, which is at the end of each of the prayers Jane Austen herself wrote.

- How should he pray? When he can’t pray from the prayer book, his father tells Frank that a brief cry to God from his heart will be just as acceptable as the formal words of the prayer book.

- What should he pray for? He should give thanks for the blessings he has received in the past, and ask God for favor and protection in the future. This is also a way of doing his “duty to God” as the Catechism states.

Vice Admiral Sir Francis Austen, later Admiral of the Fleet

Francis Austen went on to great honors in his profession, becoming Senior Admiral of the Fleet shortly before he died. He was known as a very religious officer, who never swore or allowed others to swear. His ships were considered “praying ships,” and he was known as “the officer who knelt in church.” He apparently took his father’s example and advice to heart.

__________

With grateful acknowledgment to Deirdre LeFaye, who provided a transcript of George Austen’s letter, and to Admiral Sir Francis Austen’s great-great-granddaughter, who gave permission to reproduce this section of the letter.

About Brenda S. Cox:

Brenda S. Cox writes at brendascox.wordpress.com on “Faith, Science, Joy . . . and Jane Austen!” She is working on a book entitled Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England.

Sources and Further Reading

Jane Austen’s Sailor Brothers by J. H. Hubback and Edith C. Hubback, 1906. www.mollands.net/etexts/jasb/jasb2.html Available at mollands.net, at google books, and at archive.org . You can read most of the letter in this book.

Elegant Extracts by Vicesimus Knox. London: Charles Dilly, 1784. 2nd edition. archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.94215/. The Blair quote is from extract 26.

The Book of Common Prayer. Cambridge: Baskerville, 1762. books.google.com/books/about/The_Book_of_Common_Prayer_and_Administra.html?id=_sYUAAAAQAAJ The Catechism is on p. 359 ff. of this scanned file.

Lectures on the Catechism, by Thomas Secker. London: Rivington, 1771. archive.org/details/lecturesoncatech01seck/page/n13

“Reading Prayers: The Book of Common Prayer.” brendascox.wordpress.com/2019/01/03/reading-prayers-the-book-of-common-prayer/

“Jane Austen Faith Word: Duty, and Anne Elliot” brendascox.wordpress.com/2018/03/08/jane-austen-faith-word-duty-and-anne-elliot/

“Marianne Dashwood’s Repentance, Willoughby’s ‘Repentance,’ and The Book of Common Prayer.“ Persuasions On-line Winter 2018. jasna.org/publications/persuasions-online/volume-39-no-1/cox/

“Jane Austen’s Sailor Brothers: Francis and Charles in Life and Art,” by Brian Southam. Persuasions 25. jasna.org/publications/persuasions/no25/southam/

“Sir Francis William Austen: Glimpses of Jane’s Sailor Brother in Letters” janeaustensworld.wordpress.com/2009/10/08/sir-francis-william-austen-glimpses-of-janes-sailor-brother-in-letters/

“Jane Austen’s Seagoing Brothers, Francis and Charles” https://janeaustensworld.wordpress.com/2011/12/21/janes-seagoing-brothers-francis-and-charles/

Jane Austen: The Parson’s Daughter by Irene Collins. London: Hambledon, 2007. amazon.com/dp/1852855622/

Praying With Jane by Rachel Dodge. Bloomington, MN: Bethany House, 2018. amazon.com/dp/B07D6Y5P14/