By Brenda S. Cox

“My idea of good company, Mr. Elliot, is the company of clever, well-informed people, who have a great deal of conversation; that is what I call good company.”—Anne Elliot, Persuasion

This year I enjoyed plenty of “good company” at the yearly Jane Austen Festival in Bath. Every September, Janeites gather from around the world to enjoy a wide range of events.

This year’s Jane Austen Festival was held Sept. 13-22.

After a few pre-Festival events, the 2024 Jane Austen Festival officially kicked off with a Grand Regency Costumed Promenade on Saturday morning. Organizers were expecting 1100 people in full Regency dress. We walked through Bath, from the Holbourne Museum at Sydney Gardens (near one of the Austen’s homes in Bath) all the way up to the Assembly Rooms (the “Upper Rooms” in Austen’s time).

Soldiers and musicians led the parade. The promenaders, including men and women, boys and girls, swept up the wide streets. The weather was cool and sunny, unlike the first time I attended the Festival, when it was rainy and I ended up with a muddy petticoat, like Elizabeth Bennet!

The promenade ended at the Festival Fayre in the Assembly Rooms. All kinds of Regency goods were on offer, from the wonderful Jane Austen’s Regency World Magazine to gloves, bonnets, socks, dresses, jewelry, and much more.

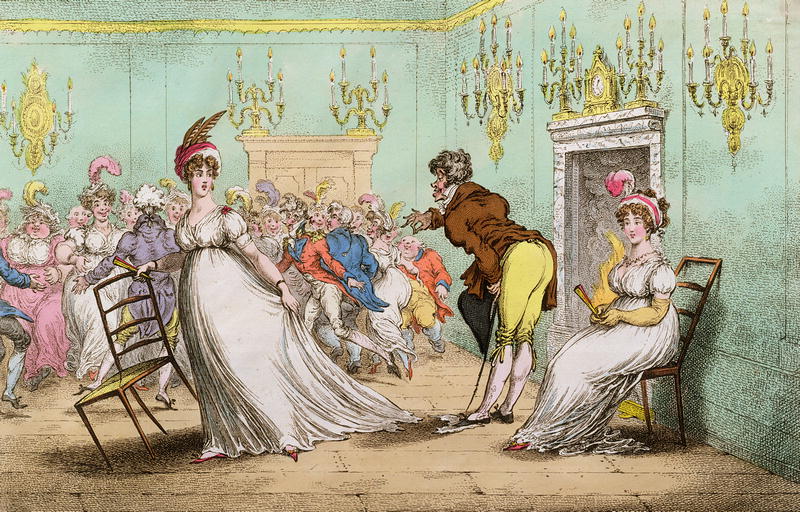

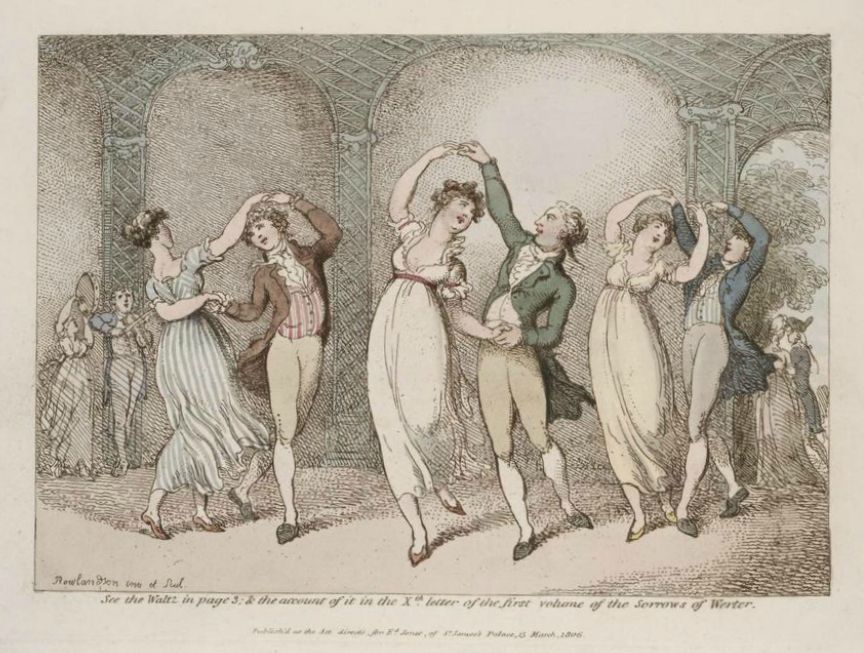

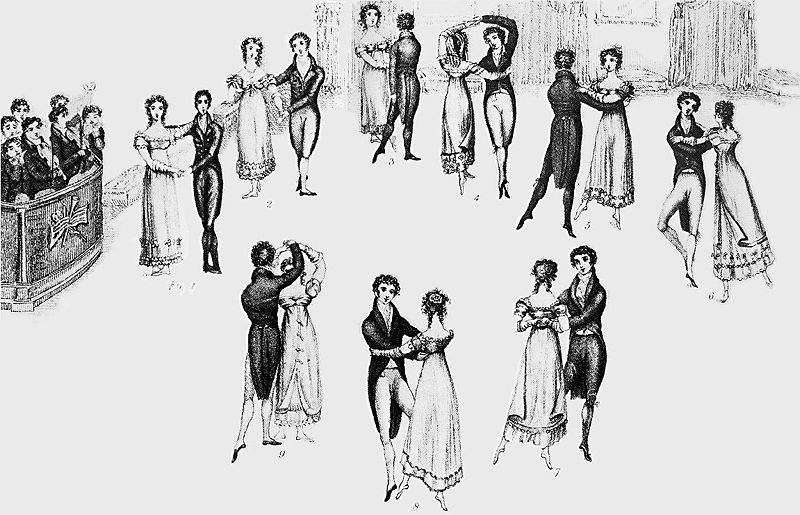

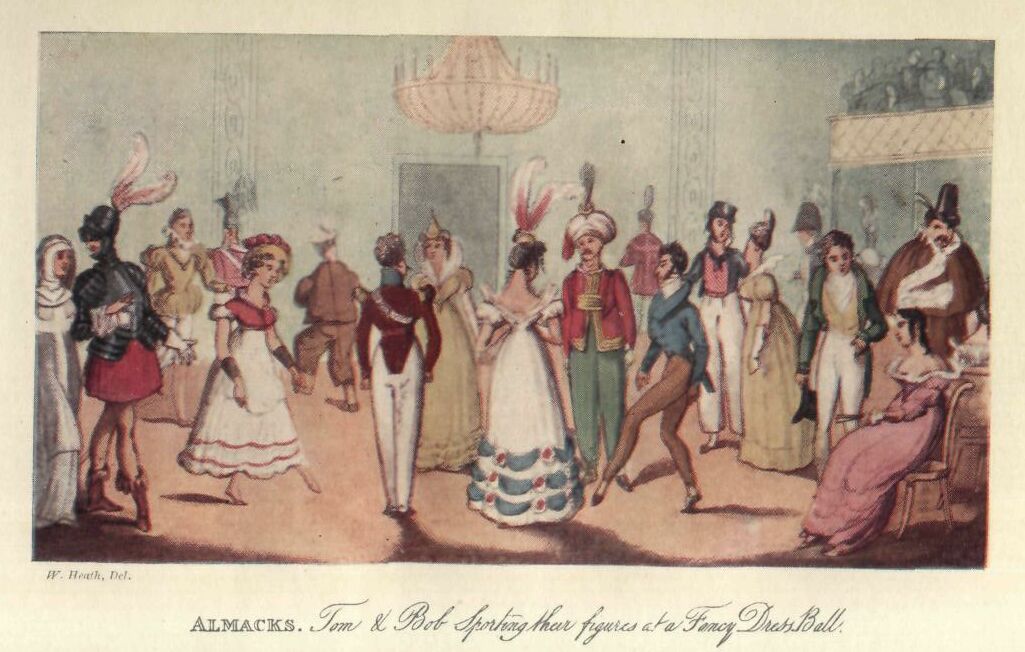

I was fortunate enough to have a ticket to the Netherfield Ball that evening. A dance workshop prepared us in the afternoon. It was quite a treat to get to dance in the Assembly Rooms! (Outside of Festival dates, the Rooms are now closed most of the time, since the Fashion Museum moved out, but tours are offered occasionally.)

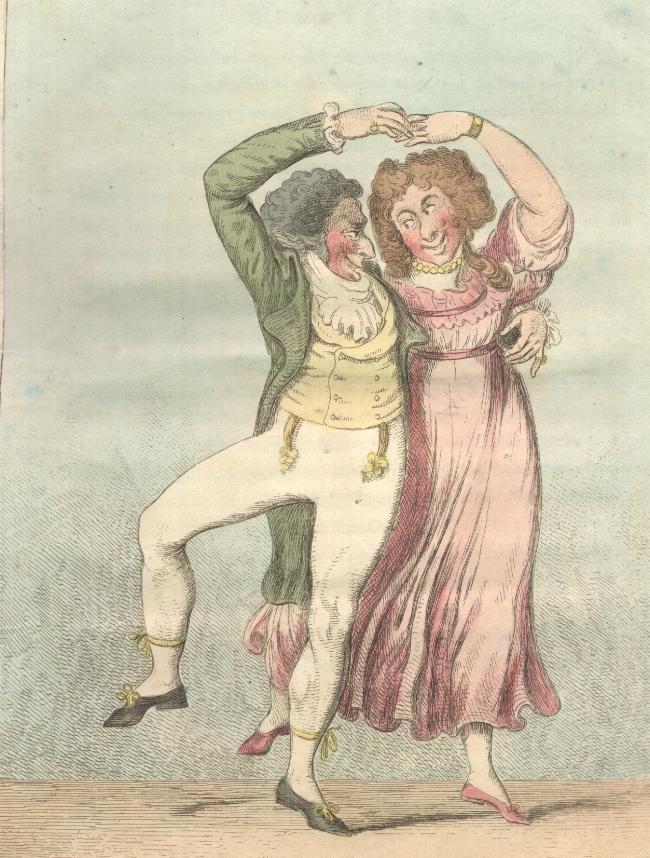

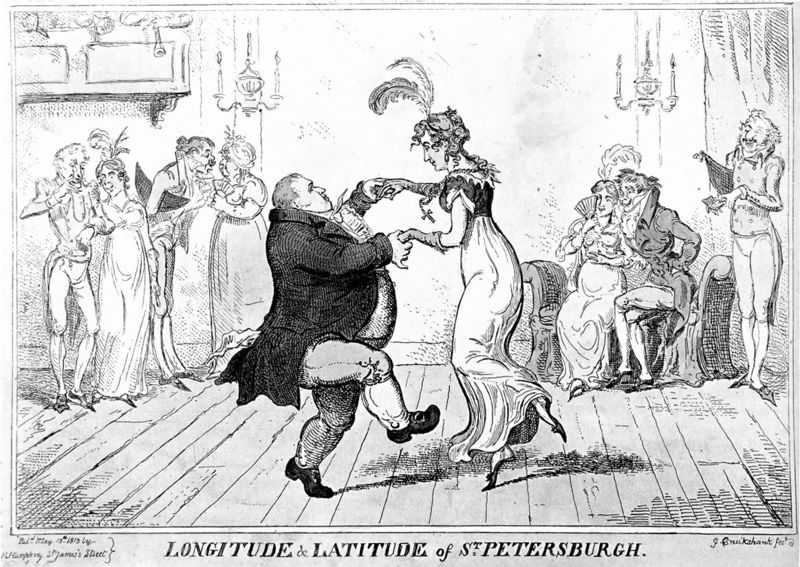

If you’ve never tried Regency dancing, the basics are not too difficult. The dance workshop gave good preparation, and the caller walked us through each dance before we danced it. You switch partners often, and ladies often dance with ladies, since gentlemen are always scarce. We all occasionally make mistakes, laugh about them, and keep dancing. This is true of all the Austen dances I’ve been to, in England and America.

This year’s Festival included three balls: one for experienced dancers on the first Friday, the Netherfield Ball I attended on the first Saturday, and a Northanger Abbey Gothic Soiree on the second Saturday, plus many dance workshops and demonstrations. Lots of dancing!

A mini-promenade rounded out the festival on the final Sunday, for those who missed the main promenade.

Many wonderful events were offered. I could only attend a small fraction of them. Here are the types of events. I’ll tell you about a few of the ones I got to participate in, then list others to give you a taste.

Tours

Though I know Bath fairly well, I signed up for an interesting tour called “Romantic chic lit or radical writer.” The guide took us around to Austen-related sites in Bath, speculating about Austen’s more radical leanings and challenges in her life.

Other tours offered, for those who wanted to see more of Bath and its surroundings: theatrical walking tour with dramatic entertainment; minibus tour to Hampshire to see places Jane Austen lived; variety of walking tours of Bath; canal cruise; minibus tour to “Meryton” and “Longbourn”; Jane Austen’s Bath homes; ghost walk; “Beastly Bath,” focusing on disagreeable aspects of the city in Austen’s time; walking tour to nearby Weston; twilight tour of the delightful No. 1 Royal Crescent, set up as an eighteenth century home; Gothic novel tour; and tour of Parade House in Trowbridge.

Workshops

I enjoyed “Singing with Jane Austen.” We learned and sang together songs from Austen’s time. Some were silly children’s songs, others songs from Austen’s music teacher.

Other workshops offered, for those who like hands-on activities: dancing, croquet, silhouette embroidery, building Northanger Abbey (drawing gothic buildings), fencing, bonnet and turban making, fabric dyeing, parasol making, Regency games, reticule making, Regency hand sewing, and making a spencer.

Musical Events

At a lovely concert in the Assembly Rooms, we got to hear music from Austen’s own collection, played on the harp and pianoforte. What a treat that was, especially hearing a harp like the one Mary Crawford enchanted Edmund with.

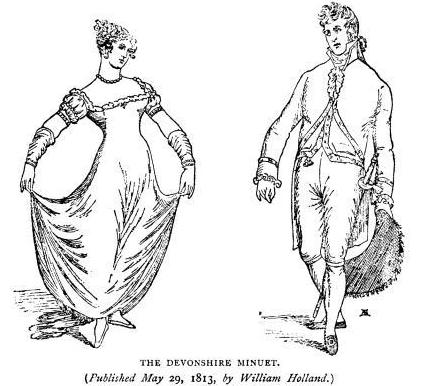

One of my favorite events was a demonstration of popular dances throughout Austen’s lifetime. The Jane Austen Dancers, in “Dancing in the Footsteps of Jane Austen,” danced them all for us, from the minuet to the waltz. They even showed us the “reel” that Mr. Darcy challenged Elizabeth to enjoy.

Gillian Dooley also spoke on Jane Austen and Music, playing and singing some of the songs. I missed that one, but I look forward to hearing her at the JASNA AGM.

Church

The “Regency Church Service” at Bath Abbey on the first Sunday included Regency church music, and many of us dressed in Regency clothes to attend. Evensong that afternoon was another chance to enjoy a lovely worship service sung by a choir of young people and adults.

Talks

I had the privilege of talking about the church in “Why Mr. Collins: The Church and Clergy in Austen’s England.” The wonderful venue was St. Swithin’s Church: the church where Austen’s parents were married, where William Wilberforce got married, and where Austen’s father is buried, as well as Fanny Burney. It’s also mentioned in Northanger Abbey as Walcot Church, since it is the parish church of Walcot.

Later in the week, I enjoyed hearing Lizzie Dunford of the Jane Austen House talk about Jane Austen and classic fairytales.

John Mullan also gave two fascinating talks, one on dancing in the novels, and one on dialogue in the novels. He shed light on many relevant quotes from the novels.

I learned more about Regency health and taking the waters at the new Bath Medical Museum. This museum is tiny and has limited opening hours, but includes helpful information and exhibits.

Other talks, for those who like me who love to learn all they can about Jane Austen’s world, covered: fashion; Jane Austen and London; the Assembly Rooms: “Romance, Rows, and Riots”; social rules about love, courtship, and marriage; movie locations; “Race for an Heir,” the royal family in Austen’s time; Austen’s life; and the theatre.

Demonstrations

I loved “Stargazing at the Herschel Museum of Astronomy with the Bath Astronomers.” We got to explore this delightful museum, early home of William and Caroline Herschel. William Herschel discovered the planet Uranus from his backyard at this building. His sister Caroline, the first professional woman astronomer, discovered a number of comets. Once it got dark, we trooped outside where we saw the space station pass overhead, watched stars, and learned about heavenly bodies from astronomers. We were all sorry to leave when the next group arrived.

In another demonstration, “a whole campful of soldiers” was set up to demonstrate drills and marching. Talks on soldiers’ wives and on dueling gave more insight into soldiers’ lives.

Accessories

I appreciate people who collect Regency items and are willing to show them to us, explain them, and even let us handle them. Two of my favorite talks were on “Rummaging through the Reticule,” showing examples of the many items a Regency lady might carry in her reticule, and “Stand and Deliver! Desirable Dress Accessories in the Georgian Age,” showing items a Regency gentleman might carry, and which a highwayman might steal. I wasn’t able to attend “The Etiquette of Dining,” but it included demonstrations with period “silver, porcelain, and domestic items.”

Discussions

It was great fun throughout the Festival to meet with other people passionate about Jane Austen and discuss her works and life together. At “Sew Chatty,” we brought our current sewing projects so we could sew together and chat, as women in Austen’s day did. “Book clubs” also met to discuss Pride and Prejudice and Mansfield Park. Our group had a lively discussion of Mansfield Park, touching on the characters of Fanny Price, Mary Crawford, Mrs. Price, and others. We wondered whether or not Fanny has a flaw to overcome and grows as a character during the novel. (What do you think?)

Food was shared, of course, at Regency breakfasts, a Sunday afternoon picnic, and high teas at “Highbury” (in the Jane Austen Centre Regency Tea Room). Other participants went on their own to enjoy tea or a meal at the Pump Room.

Other events included a Regency hair salon, a murder mystery with the audience as detectives, and several shows, including “Lady Susan.” Visitors also of course enjoyed the Roman Baths, the Royal Crescent, and other sights around Bath.

Overall I think a great time was had by all. Kudos to Georgia Delve, the Festival Director (and one of the Jane Austen Dancers), and her wonderful team who organized it all and kept everyone in the right places!

The Jane Austen Festival is a delightful opportunity to connect with other Janeites, learn, and have fun. Next year’s Festival will be Sept. 12-21. Since 2025 is the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen’s birth, special celebrations will be held and a large crowd is expected, so book your accommodations early. (I use booking.com; no doubt there are other good options.) If you’re planning to go, I recommend that you become a Festival Friend, for £35, to get first priority on booking popular events like balls; those tickets sell out quickly.

Regency dress is required for certain events—balls and promenades—but optional for others. For most events, some people dressed up, others didn’t. I was impressed that many people wore their Regency clothes around Bath all week long. I wasn’t quite that dedicated, myself. I did get great ideas for new outfits, though.

If you attended the Festival this year or in previous years, please tell us what your favorite events were.

All photos, except the program cover, © Brenda S. Cox, 2024.