As we continue our month-by-month journey through Jane Austen’s novels, letters, and lifetime, we find ourselves in the lovely month of April! If you’re just jumping on the bus, you can find previous articles in my “A Year in Jane Austen’s World” series here: January, February, and March.

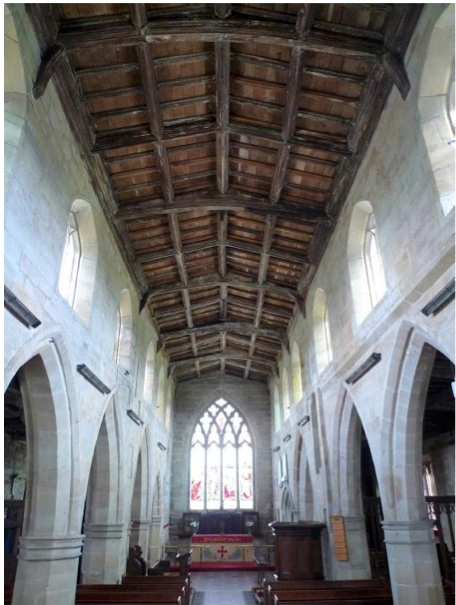

Let’s see what we find as we explore April in Jane Austen’s World! First up, our monthly view of Chawton House and Gardens, where the tulips are beginning to bloom!

April in Hampshire

April is when everything starts to come back to life and bloom in Hampshire. The trees boast new leaves, the roads and lanes are lined with green, and flowers and trees are in blossom. The weather ranges from cloudy to partly cloudy to partly sunny to rainy.

Why talk about the flowers and the weather? Because it’s fun to picture some of the details about Hampshire that Austen loved and that we can still enjoy today!

The badness of the weather disconcerted an excellent plan of mine,—that of calling on Miss Beckford again; but from the middle of the day it rained incessantly.

Letter to Cassandra, Sloane St., Thursday (April 18, 1811)

Your lilacs are in leaf, ours are in bloom. The horse-chestnuts are quite out, and the elms almost. I had a pleasant walk in Kensington Gardens on Sunday with Henry, Mr. Smith, and Mr. Tilson; everything was fresh and beautiful.

Letter to Cassandra, Sloane St., Thursday (April 25, 1811)

Here is a glimpse of Jane Austen’s House Museum this month. The garden is looking absolutely lovely already!

April in Jane Austen’s Letters

We have two letters from April 1811 when Jane was staying with her brother in Sloane Street in London. The following are a few excerpts of special interest:

April 18, 1811 Letter: Sloane Street

- Her spring shopping purchases: “I am sorry to tell you that I am getting very extravagant, and spending all my money, and, what is worse for you, I have been spending yours too; for in a linendraper’s shop to which I went for checked muslin, and for which I was obliged to give seven shillings a yard, I was tempted by a pretty-coloured muslin, and bought ten yards of it on the chance of your liking it; but, at the same time, if it should not suit you, you must not think yourself at all obliged to take it; it is only 3s. 6d. per yard, and I should not in the least mind keeping the whole. In texture it is just what we prefer, but its resemblance to green crewels, I must own, is not great, for the pattern is a small red spot. And now I believe I have done all my commissions except Wedgwood.”

- More walking and shopping: “I liked my walk very much; it was shorter than I had expected, and the weather was delightful. We set off immediately after breakfast, and must have reached Grafton House by half-past 11; but when we entered the shop the whole counter was thronged, and we waited full half an hour before we could be attended to. When we were served, however, I was very well satisfied with my purchases — my bugle trimming at 2s. 4d. and three pair silk stockings for a little less than 12s. a pair.”

- News about their brothers and their careers in the Navy: “Frank is superseded in the ‘Caledonia.’ Henry brought us this news yesterday from Mr. Daysh, and he heard at the same time that Charles may be in England in the course of a month. Sir Edward Pollen succeeds Lord Gambier in his command, and some captain of his succeeds Frank; and I believe the order is already gone out. Henry means to inquire farther to-day. He wrote to Mary on the occasion. This is something to think of. Henry is convinced that he will have the offer of something else, but does not think it will be at all incumbent on him to accept it; and then follows, what will he do? and where will he live?”

April 25, 1811 Letter: Sloane Street

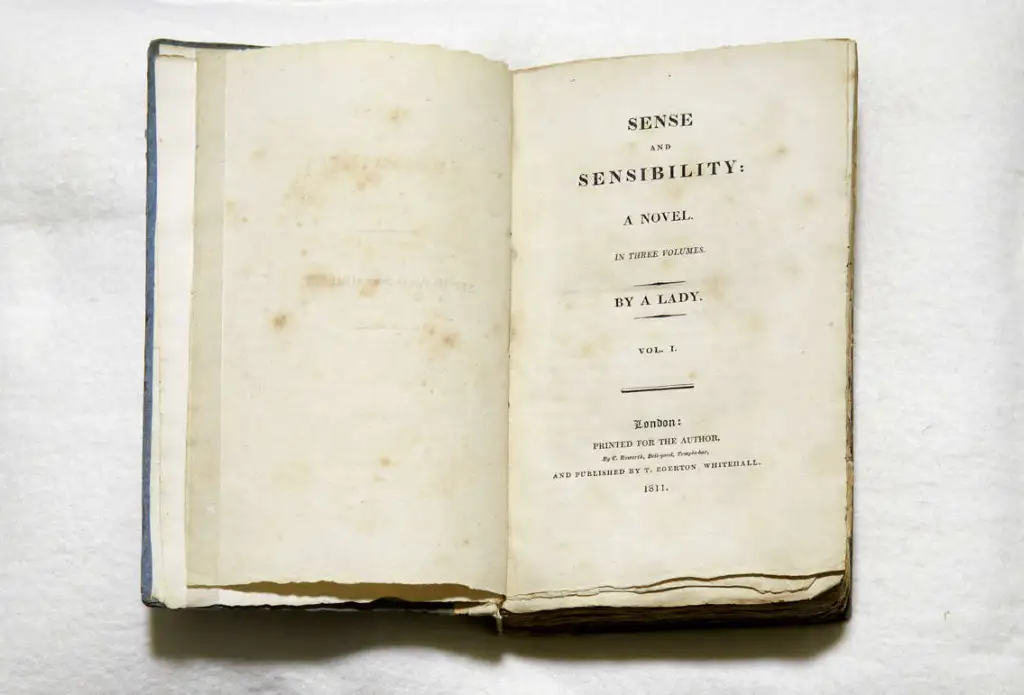

- Austen’s progress with and thoughts about Sense and Sensibility: “No, indeed, I am never too busy to think of S. and S. I can no more forget it than a mother can forget her sucking child; and I am much obliged to you for your inquiries. I have had two sheets to correct, but the last only brings us to Willoughby’s first appearance. Mrs. K. regrets in the most flattering manner that she must wait till May, but I have scarcely a hope of its being out in June. Henry does not neglect it; he has hurried the printer, and says he will see him again to-day. It will not stand still during his absence, it will be sent to Eliza.”

- Plenty of wonderful details about a party hosted by Henry and Eliza: “Including everybody we were sixty-six — which was considerably more than Eliza had expected, and quite enough to fill the back drawing-room and leave a few to be scattered about in the other and in the passage.”

- “The music was extremely good. It opened (tell Fanny) with ‘Poike de Parp pirs praise pof Prapela’; and of the other glees I remember, ‘In peace love tunes,’ ‘Rosabelle,’ ‘The Red Cross Knight,’ and ‘Poor Insect.’ Between the songs were lessons on the harp, or harp and pianoforte together; and the harp-player was Wiepart, whose name seems famous, though new to me. There was one female singer, a short Miss Davis, all in blue, bringing up for the public line, whose voice was said to be very fine indeed; and all the performers gave great satisfaction by doing what they were paid for, and giving themselves no airs. No amateur could be persuaded to do anything.”

- “The house was not clear till after twelve. If you wish to hear more of it, you must put your questions, but I seem rather to have exhausted than spared the subject.”

April in Jane Austen’s Novels

The following are a collection of interesting details and scenes that occur in (or refer to) the month of April in Austen’s novels. Springtime appears to be a good time for travel, walking, and riding as the weather slowly improves:

Sense and Sensibility

- The Palmers, Mrs. Jennings, and the Dashwood sisters leave London for Cleveland in April (for the Easter holidays): “Very early in April, and tolerably early in the day, the two parties from Hanover Square and Berkeley Street set out from their respective homes, to meet, by appointment, on the road. For the convenience of Charlotte and her child, they were to be more than two days on their journey, and Mr. Palmer, travelling more expeditiously with Colonel Brandon, was to join them at Cleveland soon after their arrival.”

Pride and Prejudice

- Darcy proposes again and refers to his first April proposal to Elizabeth Bennet (he surely remembers that date VERY well): “You are too generous to trifle with me. If your feelings are still what they were last April, tell me so at once. My affections and wishes are unchanged; but one word from you will silence me on this subject for ever.”

Mansfield Park

- Fanny is left without fitting exercise: “[The Miss Bertrams] took their cheerful rides in the fine mornings of April and May; and Fanny either sat at home the whole day with one aunt, or walked beyond her strength at the instigation of the other: Lady Bertram holding exercise to be as unnecessary for everybody as it was unpleasant to herself; and Mrs. Norris, who was walking all day, thinking everybody ought to walk as much.”

- Sir Thomas’s letter home: “[Sir Thomas] wrote in April, and had strong hopes of settling everything to his entire satisfaction, and leaving Antigua before the end of the summer.”

- Fanny Price in Portsmouth: “The end of April was coming on; it would soon be almost three months, instead of two, that she had been absent from them all, and that her days had been passing in a state of penance, which she loved them too well to hope they would thoroughly understand; and who could yet say when there might be leisure to think of or fetch her?”

- Fanny’s thoughts on springtime in the countryside versus the congested town: “It was sad to Fanny to lose all the pleasures of spring. She had not known before what pleasures she had to lose in passing March and April in a town. She had not known before how much the beginnings and progress of vegetation had delighted her. What animation, both of body and mind, she had derived from watching the advance of that season which cannot, in spite of its capriciousness, be unlovely, and seeing its increasing beauties from the earliest flowers in the warmest divisions of her aunt’s garden, to the opening of leaves of her uncle’s plantations, and the glory of his woods. To be losing such pleasures was no trifle; to be losing them, because she was in the midst of closeness and noise, to have confinement, bad air, bad smells, substituted for liberty, freshness, fragrance, and verdure, was infinitely worse: but even these incitements to regret were feeble, compared with what arose from the conviction of being missed by her best friends, and the longing to be useful to those who were wanting her!

Northanger Abbey

- Isabella writes a “very unexpected letter” to Catherine.

Emma

- Mrs. Elton pressures Jane to find a position as a governess very soon so that she doesn’t miss her chance: “But, my dear child, the time is drawing near; here is April, and June, or say even July, is very near, with such business to accomplish before us. Your inexperience really amuses me! A situation such as you deserve, and your friends would require for you, is no everyday occurrence, is not obtained at a moment’s notice; indeed, indeed, we must begin inquiring directly.”

- For the introverts among us: “John Knightley only was in mute astonishment.—That a man (Mr. Weston) who might have spent his evening quietly at home after a day of business in London, should set off again, and walk half a mile to another man’s house, for the sake of being in mixed company till bed-time, of finishing his day in the efforts of civility and the noise of numbers, was a circumstance to strike him deeply. A man who had been in motion since eight o’clock in the morning, and might now have been still, who had been long talking, and might have been silent, who had been in more than one crowd, and might have been alone!—Such a man, to quit the tranquillity and independence of his own fireside, and on the evening of a cold sleety April day rush out again into the world!“

April Dates of Importance

This brings us now to several dates that would have been important to Austen personally and to the Austen family as a whole:

Family News:

26 April 1764: Rev. George Austen marries Cassandra Leigh.

23 April 1774: Francis (Frank) Austen (Jane’s brother) born at Steventon.

April 1786: Francis Austen enters the Royal Naval Academy at Portsmouth

15 April 1793: James Austen’s first child, Anna, is born.

Historic Dates:

19 April 1775: The Battle of Lexington marks the start of America’s Revolutionary War.

Writing:

April 1811: Austen continues to correct proofs of Sense and Sensibility. She anticipates its publication date.

Sorrows:

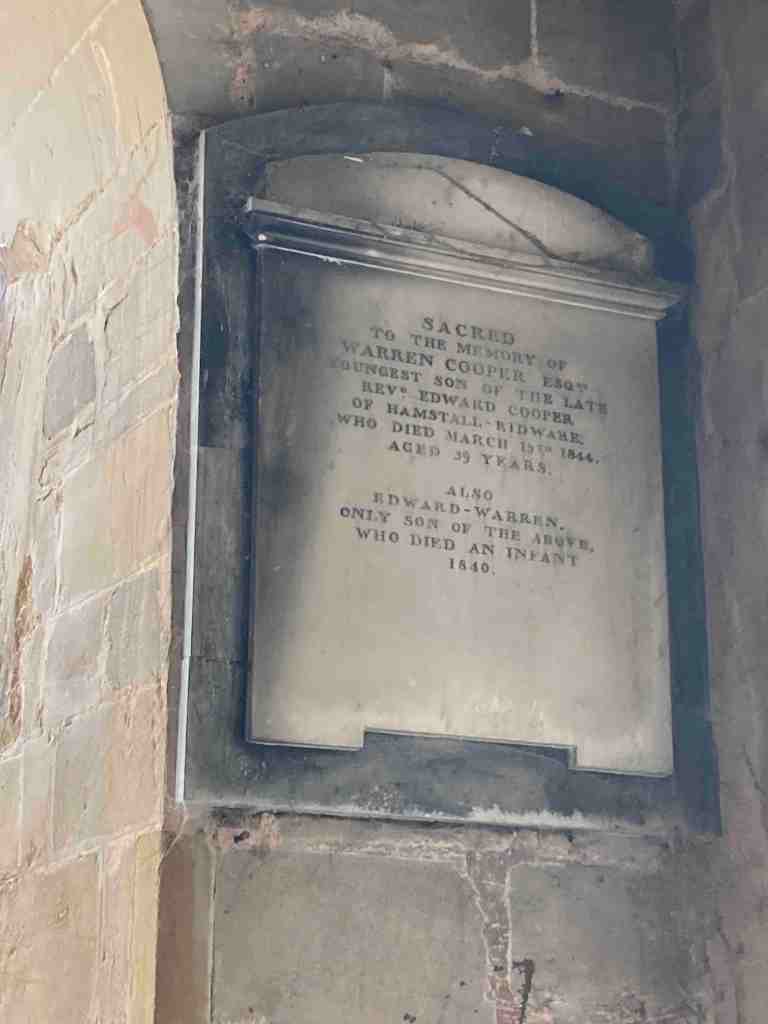

22 April 1813: Eliza de Feuillide (Austen’s cousin and, later, sister-in-law) ill. Jane Austen goes to her bedside in London to help attend to her.

25 April 1813: Eliza de Feuillide dies.

27 April 1817: Austen drafts her will:

“I Jane Austen of the Parish of Chawton do by this my last Will & Testament give and bequeath to my dearest Sister Cassandra Elizth everything of which I may die possessed, or which may be hereafter due to me, subject to the payment of my Funeral Expences, & to a Legacy of £50. to my Brother Henry, & £50. to Mde Bigeon–which I request may be paid as soon as convenient. And I appoint my said dear Sister the Executrix of this my last Will & Testament.”

April Showers

As we continue through the year, one of the highlights for me has been surveying the photos of the gardens at Chawton House and Jane Austen’s House each month and seeing the changes therein. I hope these April showers will bring many beautiful May flowers next month as we continue our tour of Hampshire in the spring with May in Jane Austen’s World!

RACHEL DODGE teaches college English classes, gives talks at libraries, teas, and book clubs, and writes for Jane Austen’s World blog. She is the bestselling author of The Little Women Devotional, The Anne of Green Gables Devotional and Praying with Jane: 31 Days Through the Prayers of Jane Austen. Now Available: The Secret Garden Devotional! You can visit Rachel online at www.RachelDodge.com.