Inquiring readers: Paul Emanuelli, author of Avon Street, has contributed a post for this blog before about the City of Bath as a Character. He has graciously sent in an article about crime and an incident involving Jane Austen’s aunt, Mrs James Leigh-Perrot. Paul writes about Bath in his own blog, unpublishedwriterblog. It is well worth a visit!

Apart from the Bow Street Runners in London there was no organised police force in 18th Century England. The capture and prosecution of criminals was largely left to their victims to deal with. Every parish was obliged to have one or two constables, but they were unpaid volunteers working only in their spare time. A victim of crime who wanted a constable to track down and arrest the perpetrator was expected to pay the expenses of their doing so.

Sometimes victims of crime hired a thief-taker to pursue the wrong-doer. Again, they were private individuals working much like latter day bounty hunters. Sometimes, thief-takers would act as go-betweens, negotiating the return of stolen goods for a fee. Many though were corrupt, actually initiating and organising the original theft in order to claim the reward for the return of goods, or extorting protection money from the criminals they were supposed to catch.

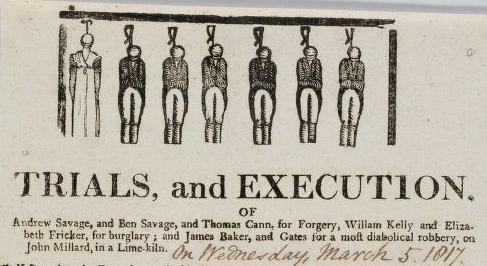

For the most part, unless a criminal was “caught in the act” (probably) by their intended victim it was unlikely they would be brought to justice. In the absence of a police force, the maintenance of “Law and Order” therefore came to depend more on deterrence rather than apprehension and the harshest penalty of all came to cover more and more crimes. In 1799 there were 200 offences that carried the death penalty, including the theft of items with a monetary value that exceeded five shillings.

In practice, judges and juries often recognised the barbarity of the punishment in relation to the crime. Juries might determine that goods were over-priced and bring their value down below the five shilling threshold. Defendants might claim “benefit of clergy” which by virtue of stating religious belief and reading out an oath allowed the judge to exercise leniency. In other cases the Government could review the sentence. Between 1770 and 1830, 35,000 death sentences were handed down in England and Wales, but only 7000 executions were actually carried out.

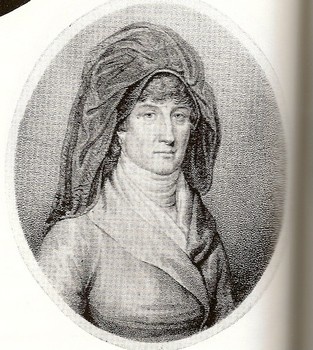

On the 8th August 1799, Jane Leigh-Perrot was accused of stealing a card of white lace from a millinery shop in Bath. The Leigh-Perrots, a wealthy couple, were Jane Austen’s mother’s brother and sister-in-law (Jane’s Uncle and Aunt). The white lace valued at £1 was found in Mrs Leigh-Perrot’s possession together with a card of black lace that she had bought and paid for from the same shop. Mrs Leigh-Perrot denied stealing the lace, saying that the sales clerk must have given it her by mistake when he handed over her purchase. She was nevertheless arrested on a charge of “grand theft” and the lace she was said to have stolen was worth four times the five shillings that carried the death sentence.

In practice it was unlikely (given her standing) that if she had been found guilty she would have been sentenced to death. The alternatives, however, included branding or transportation to the Australian Colonies with the prospect of forced labour for 14 years. Jane Leigh-Perrot was refused bail and committed to prison on the sworn depositions of the shopkeeper. Due to her wealth, social standing and age she was allowed to stay in the house of the prison keeper, Mr Scadding, at the Somerset County Gaol in Ilchester, rather than being kept in a cell. Mrs Leigh-Perrot still wrote though that she suffered ‘Vulgarity, Dirt, Noise from morning till night’. James Leigh-Perrot insisted on remaining with her in prison.

During her trial Jane Leigh-Perrot spoke eloquently for herself. Several testimonials as to her character were also read out to the court. At the conclusion of the trial the jury took only 10 minutes to find her “Not Guilty.” It does, however, make you wonder how someone less well refined, less well-connected, less eloquent, less educated, less wealthy might have fared. The evidence of her guilt, might have been quite sufficient to send someone else to the gallows, or transported, or branded with a hot iron. She was after all caught in possession of the item and identified by the shop-keeper. In “Persuasion” Captain Harville asks Anne Elliot, ‘But how shall we prove anything?’ Anne replies, ‘We never shall.’