Copryright (c) Jane Austen’s World. This post is in honor of Thanksgiving and all the cooks, feminine or masculine, who toil hard in the kitchen to feed their families on this special holiday.

I am sure that the ladies there had nothing to do with the mysteries of the stew-pot or the preserving-pan” – James Edward Austen-Leigh, writing about his aunts, Jane and Cassandra Austen, and grandmother, Mrs Austen, when they lived at Steventon Rectory.

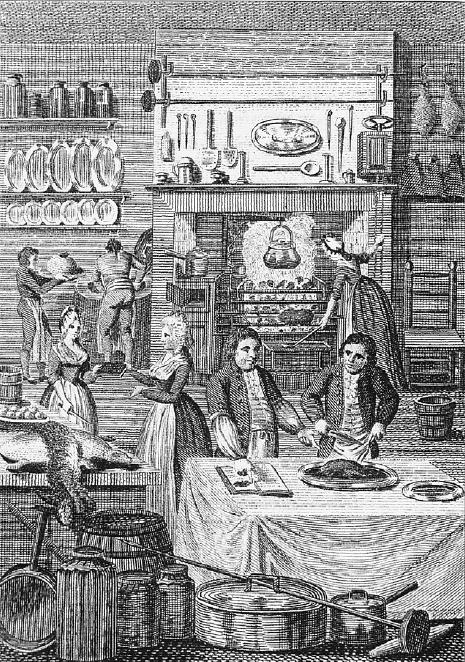

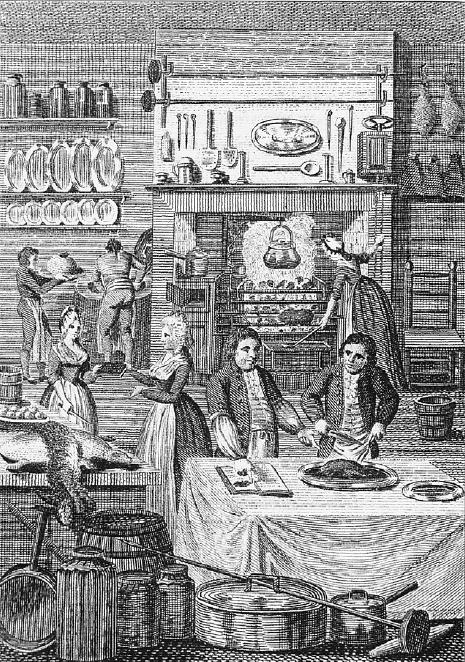

18th century kitchen servants prepare a meal. Image @Jane Austen Cookbook

In 1747, Mrs.Hannah Glasse wrote her historic The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, an easy-to-understand cookbook for the lower class chefs who cooked for the rich. Her recipes were simple and came with detailed instructions, a revolutionary thought at the time.

The Art of Cookery’s first distinction was simplicity – simple instructions, accessible ingredients, an accent on thrift, easy recipes and practical help with weights and timing. Out went the bewildering text of former cookery books (“pass it off brown” became “fry it brown in some good butter”; “draw him with parsley” became “throw some parsley over him”). Out went French nonsense: no complicated patisserie that an ordinary cook could not hope to cook successfully. Glasse took into account the limitations of the average middle-class kitchen: the small number of staff, the basic cooking equipment, limited funds. – Hannah Glasse, The Original Domestic Goddess forum

Hannah Glasse's The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy

Until Mrs. Glasse wrote her popular cookery book (17 editions appeared in the 18th century), these instructional books had been largely written by male chefs who offered complicated French recipes without detailed or practical directions. (To see what I mean, check Antonin Careme’s recipe for Les Petits Vol-Au-Vents a la Nesle at this link.) Like Jane Austen, Hannah signed her books “By a Lady”.

Antonin Careme's cookbook

Mrs. Glasse had always intended to sell her cookery book to mistresses of gentry families or the rising middle class, who would then instruct their cooks to prepare foods from her simplified recipes, which she collected. “My Intention is to instruct the lower Sort [so that] every servant who can read will be capable of making a tolerable good Cook,” she wrote in her preface.

Frontispiece from William Augustus Henderson, The Housekeeper’s Instructor, 6th edition, c.1800. This same picture appeared in the very first edition of c.1791and it shows the mistress presenting the cookery book to her servant, while a young man is instructed in the art of carving with the aid of another book.*

Hanna’s revolutionary approach, which included the first known printed recipe for curry and instructions for making a hamburger, made sense. In the morning, it was the custom of the mistress of the household to speak to the cook or housekeeper about the day’s meals and give directions for the day. The servants in turn would interpret her instructions. (Often their mistress had to read the recipes to them, for many lower class people still could not read.)

In theory, the recipes from Hannah’s cookbook would help the lady of the house stay out of the kitchen and enjoy a few moments of free time. But the servant turnover rate was high and often the mistress had to roll up her sleeves and actively participate in the kitchen. Many households with just two or three servants could not afford a mistress of leisure, and they, like Mrs. Austen in the kitchens of Steventon Rectory and Chawton Cottage, would toil alongside their cook staff.

The simple kitchen at Chawton cottage. Image @Tony Grant

At the start of the 18th century the French courtly way of cooking still prevailed in genteel households. As the century progressed, more and more women like Hannah Glasse began to write cookery books that offered not only simpler versions of French recipes, but instructions for making traditional English pies, tarts, and cakes as well. Compared to the expensive cookbooks written by male chefs, cookery books written by women were quite affordable, for they were priced between 2 s. and 6 d.

Hannah Glasse's practical directions for boiling and broiling

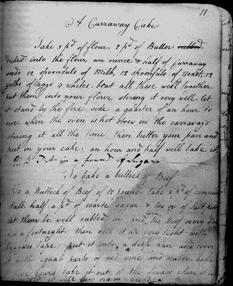

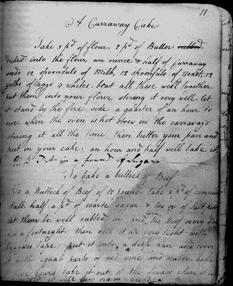

Publishers took advantage of the brisk trade, for with the changes in agricultural practices, food was becoming more abundant for the rising middle classes. Large editions of cheap English cookery books by a variety of female cooks were distributed to a wide new audience of less wealthy and largely female readers who had money to spend on food. Before Hannah Glasse and her cohort, cooks and housewives had been accustomed to sharing recipes in private journals (such as Marthat Lloyd’s) or handing them down by word-of-mouth.

Martha Lloyd's recipe for caraway cake written in her journal.

Female authors tended to share their native English recipes in their cookery books. As the century progressed, the content of these cookery books began to change. Aside from printing recipes, these books began to include medical instructions for poultices and the like; bills of fare for certain seasons or special gatherings; household and marketing tips; etc.

Bill of fare for November, The Universal Cook, 1792

By the end of the 18th century, cookery books also included heavy doses of servant etiquette and moral advice. At this time plain English fare had replaced French cuisine, although wealthy households continued to employ French chefs as expensive status symbols. In the mid-19th century cookery books that targeted the working classes, such as Mrs. Beeton’s famous book on Household Management, began to be serialized in magazines, as well as published in book form.

Family at meal time

Before ending this post, I would like to refer you back to James Edward Austen-Leigh’s quote at top. In contrast to what he wrote (for he did not know his aunts or grandmother well), Jane Austen scholar Maggie Lane reminds us that housewives who consulted with their cook and housekeeper about the day’s meals still felt comfortable working in the kitchen. She writes in Jane Austen and Food:

“though they may not have stirred the pot or the pan themselves, Mrs. Austen and her daughters perfectly understood what was going on within them…The fact that their friend and one-time house-mate Martha Lloyd made a collection of recipes to which Mrs. Austen contributed is proof that the processes of cookery were understood by women of their class.”

More on the topic:

Read Full Post »

In 1802, the Oxford English Dictionary defined Hamburg steak as salt beef. It had little resemblance to the hamburger we know today. It was a hard slab of salted minced beef, often slightly smoked, mixed with onions and breadcrumbs. The emphasis was more on durability than taste. “ – Hamburger History