Dear Readers, Happy Holidays! If you happen to stand under a sprig of mistletoe (these days it is most likely artificial), you will probably hug or kiss the person standing nearest you. This tradition did not appear in English literature until the 18th century. The practice of gathering mistletoe began in the second century BC with the Druids in ancient Britain. They gathered the parasitic plant at the start of winter from the sacred oak as a symbol of hope, peace, and harmony. Sprigs were hung in homes to herald good fortune. The plants were also used for medicinal purposes to promote female fertility and as an antidote for poison. Today we associate mistletoe boughs with Christmas. Gathered on this page are a few quotes from various sources.

The Mistletoe Season

Down South for the past month all the boys and girls who want to earn money have been gathering mistletoe.

Weeks before the Christmas-time, these young people begin to hunt the woods for mistletoe. Having found it, they watch it growing. If they find that some one else watching the same bunch, they announce it is their mistletoe.

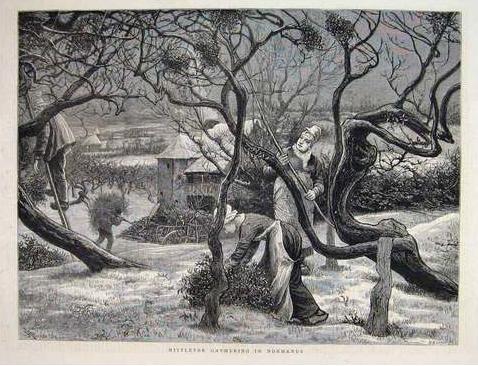

The mistletoe grows on the tree, but is no more a part of the tree than the moss with which Northern children are familiar, or vines that climb up the outside of the tree. The mistletoe grows high up in the tree and, if out on a slender branch, must be reached after with a stick and pulled off gently. Even then it is not out of danger, for the beauty is marred if the little plant falls to the ground. – New outlook, Volume 52, edited by Alfred Emanuel Smith, Francis Walton Outlook Publishing Company, Inc., U.S., 1895, p. 1146

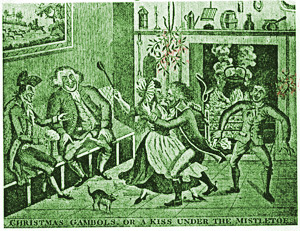

Mistletoe sprigs decorated chandeliers, doorways, and ceilings.

A ball of mistletoe, ornamented with ribbons, would be hung around Christmastime, and no unmarried girl could refuse a kiss if she was underneath it. At every kiss, the boy would pluck one of the mistletoe berries, and when there were no more berries, the ball was taken down until the next year. If a girl didn’t receive a mistletoe kiss by the time the ball was taken down, she couldn’t expect to marry in the following year. So the kiss could be a promise of marriage or a symbol of admiration, but it was also a kind of mystical fortune-telling trick. – Apartment Therapy – History of the Mistletoe

The best time for gathering mistletoe is in November after a few frosts have fallen and before the sap freezes, though it may be gathered and used at any period of the year. When gathered it should at once be spread out to dry as it will mould in a very short time if kept in a box or sack. It is best to dry it in the shade. – United States medical investigator, 1878, p 132.

Mistletoe grew in England and the United States. The common mistletoe of England grew on orchard trees and forest trees, and seldom on oak trees, which is why Druids revered it for its rarity. Mistletoe sapped the strength of apple trees in Brittany and Normandy. There it was gathered for the London market. The American mistletoe grows on deciduous trees, especially the tupelo poplar and red maple, from New Jersey, southern Indiana and east Kansas, to the Gulf. – The Standard reference work: for the home, school and library, Volume 5, edited by Harold Melvin Stanford Standard Education Society, 1921

By the Victorian era, there was scarcely a house or cottage that did not have mistletoe at Christmas time.

Down with the rosemary, and so,

Down with the baies and Mistletoe;

Down with the holly, ivie, all,

Wherewith ye dressed the Christmas Hall.

The damsel donn’d her kirtle sheen;

The hall was dress’d with holly green,

Forth to the wood did merry men go

To gather in the Mistletoe.”

– English botany, or, coloured figures of British plants, Volume 4, By James Sowerby G. Bell, 1873