By Brenda S. Cox

“The Prices were just setting off for church the next day when Mr. Crawford appeared again. He came, not to stop, but to join them; he was asked to go with them to the Garrison chapel, which was exactly what he had intended, and they all walked thither together.”—Mansfield Park, chapter 42

Real Churches in Austen’s Novels

The Garrison Chapel (now called the Garrison Church) is one of a handful of specific, real churches Jane Austen mentions in her novels.

- In Northanger Abbey, John Thorpe passes “Walcot Church,” St. Swithin’s on the edge of Bath. We hear about the “church-yard” in Bath, adjacent to Bath Abbey, though the Abbey is not named. Catherine Morland looks for the “well-known spire” of Salisbury Cathedral on her way home. (See “Churches, Chapels, Abbeys, and Cathedrals in Northanger Abbey”.)

- In Pride and Prejudice, Wickham and Lydia get married at St. Clement’s in London, possibly St. Clement Danes in London’s city of Westminster, or St. Clement Eastcheap, near London Bridge. By the way, it’s not clear which of those is the St. Clement’s of the old nursery rhyme about London church bells, which begins “Oranges and lemons, say the bells of St. Clement’s.”

- In Mansfield Park, Mary Crawford mentions St. George’s, Hanover Square (in Mayfair, London) as a place for weddings. Dr. Grant seeks a promotion to Westminster Abbey or St. Paul’s Cathedral (he gains a prebendal stall at Westminster). And the Prices attend church at the “Garrison Chapel” in Portsmouth.

All these churches can still be visited, though the Garrison Church is partly in ruins. (Have I missed any churches named in Austen’s novels? Let me know in the comments if you have noticed others!)

The Garrison Chapel in Portsmouth

What was the Garrison Chapel? It was called a chapel, not a church, at that time, since “church” meant the Church of England main church of a parish. There were several types of chapels. This one was an institutional chapel, connected to a certain place or group of people. It was the chapel for military troops serving in Portsmouth. Since Fanny Price’s father was a “lieutenant of marines,” this was the logical place for her family to worship.

Mansfield Park tells us, “In chapel they were obliged to divide, but Mr. Crawford took care not to be divided from the female branch.” Roger E. Moore, in Jane Austen and the Reformation, explains, “officers and sailors sit separately from civilians” (124). Presumably Fanny’s father joined his friends, his “brother loungers,” in one section, while his family, with Henry Crawford, sat in a different section.

Origins

The Garrison Church building dates all the way back to 1212 A. D., over 800 years ago. The Bishop of Winchester founded it as a “hospital” called the “Domus Dei,” or “House of God.” It was not a place for medical care, but a place of hospitality. The poor, the ill, and people on pilgrimage could come there and find rest. Beds lined what later became the nave of the church.

Mass was said regularly in a chapel at the east end of the building. Residents would either attend services or listen from their beds if they could not stand. A priest was in charge, aided by twelve poor men or women. They helped look after visitors in exchange for bread, ale, and a place to stay.

According to Moore, the main hall was “surrounded by a complex of auxiliary buildings, including a master’s house and hall, kitchen, bakehouse, stable, and lodgings for the brothers and sisters who staffed it” (124-5). Income from nearby houses and land supported the work, just as medieval monasteries were supported by nearby properties.

Moore says that the mention of this place in Mansfield Park is significant. The “Domus Dei” (which later became the Garrison Chapel) gladly welcomed anyone who appeared there asking for entrance, regardless of social status. It is contrasted with Mansfield Park, where Mrs. Norris does not “gladly” welcome poor Fanny to the parsonage where she and her husband live. Even the Bertrams give Fanny only a small attic room, without even a fire for warmth. Moore also points out that when Fanny sees Henry in Portsmouth, she is impressed that he has been acting as a “friend to the poor and oppressed,” just as the brothers and sisters at the Domus Dei had done for many.

The hospital closed in 1540 when King Henry VIII suppressed the monasteries and other religious houses, including most such hospitals. Valuables were stripped from it, and the buildings were used to store munitions. Queen Elizabeth I expanded the fortifications at Portsmouth, made the large dormitory into a chapel for the garrison, and the rest of the buildings became the home of the garrison’s governor.

(Source: a guidebook in the church)

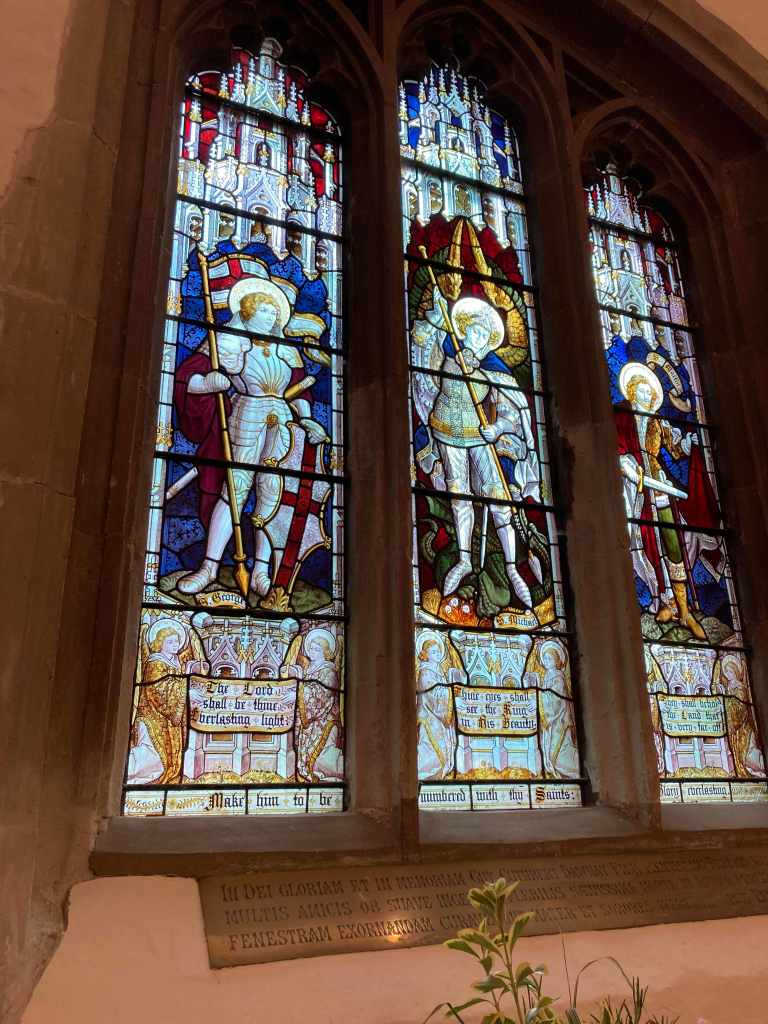

In 1826, the Governor’s house next to the chapel was demolished. Forty years later, restoration work began on the church (now called a church rather than a chapel), balancing “the original medieval appearance with Victorian needs and preferences,” according to a sign at the site. A new altar, pulpit, and stalls were added.

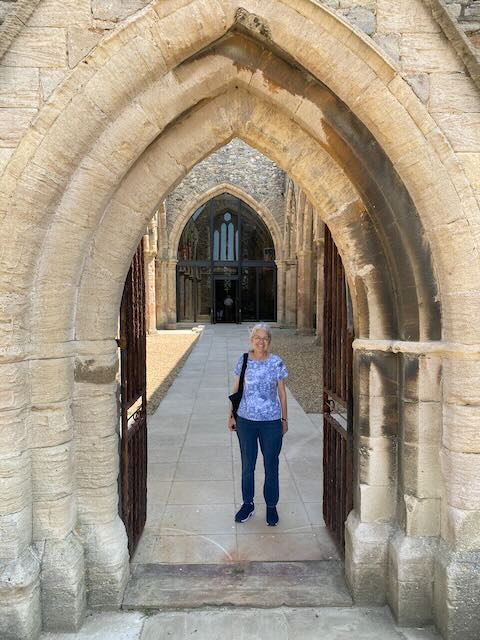

Garrison Church Today

The church was bombed in 1941, destroying much of the roof of the nave (the large hall that used to be the hospital). However, the smaller worship area, the chancel, survived and continued to be used. See this site for more about the church’s history.

Apparently the church is still in use for occasional services for the military. It is open to the public on certain days and times, for free; check the website before going.

In Portsmouth Harbor you can also visit HMS Victory, Lord Nelson’s ship, which is undergoing a thorough restoration. The cruise we took of the harbor was lovely. On the same day, my friends and I also visited Netley Abbey. Nearby Southampton has a few sites related to Austen. However, we were not allowed to enter the Dolphin Hotel, where she danced. You can only see it from the street.

There’s so much history and meaning in Jane Austen’s mildest references. I’m thankful for the many people who have preserved and kept alive the places that were important to Austen and to her characters, including the Garrison Chapel.

All photos ©Brenda S. Cox, 2024. Please ask permission before using.

Sources

Roger E. Moore, Jane Austen and the Reformation

Excellent signs and booklet at the church

Real Churches in Austen’s Novels and Letters

St. Swithin’s, Walcot and other churches in Northanger Abbey

St. Paul’s, Covent Garden: Actors’ Church

Austen Family Churches

Hamstall Ridware and Austen’s First Cousin, Edward Cooper

Adlestrop and the Leigh Family

Stoneleigh Abbey Chapel and Mansfield Park