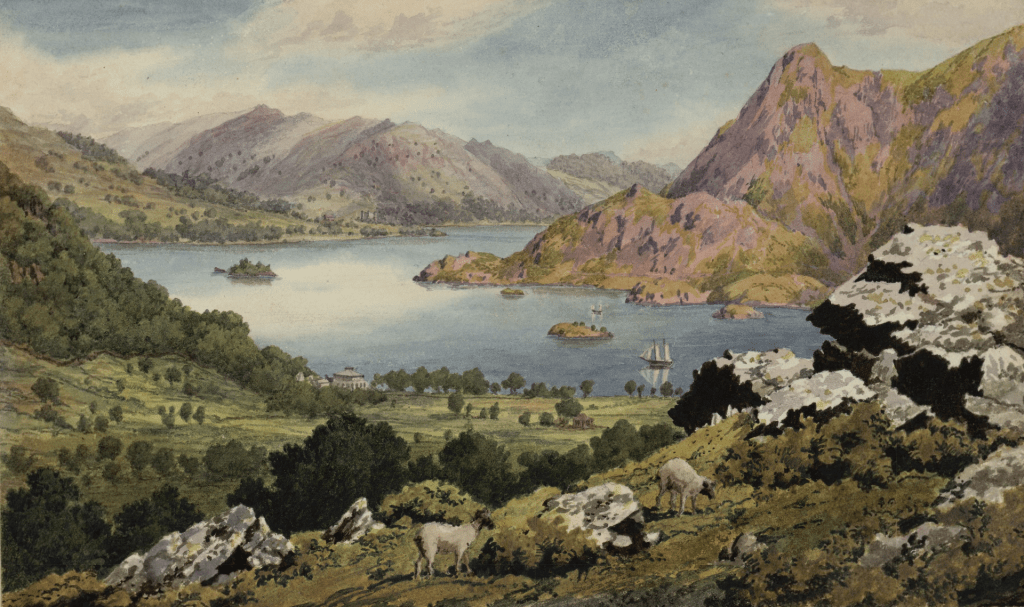

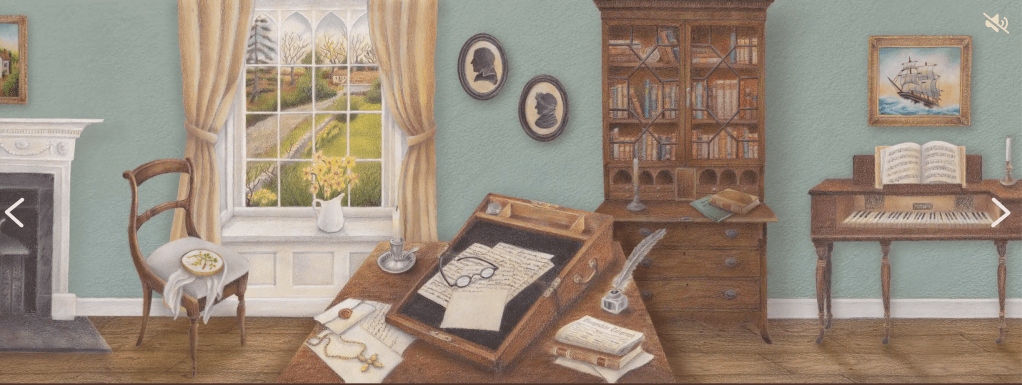

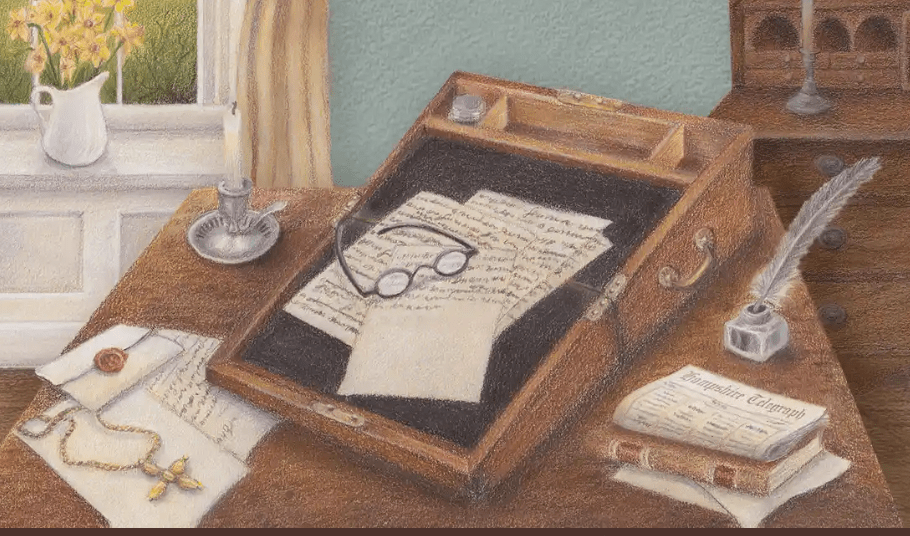

Inquiring readers: We readers of Jane Austen’s novels, letters, and stories, as well as of the history of the Georgian/Regency era in England, are fairly knowledgeable about the modes of travel for the upper classes and rising middle classes – from grand carriages to fast paced curricles to the humbler donkey cart that the Austen women drove from Chawton to the nearby village of Alton (1.6 miles away). A majority of these vehicles (except perhaps for the donkey cart) were beyond the means of most of the working classes, as well as the poor. (Just one horse cost an average of £500 per year to maintain. Even Rev Austen used his horse for a variety of jobs: to visit his parishes, post letters in town, and for farm work.). So how did humbler citizens travel? What modes of transportation were affordable and available to them?

Chawton to Alton. Google map

On Foot:

If memory serves me well (from an article I read 20 years ago), most villagers in Austen’s day moved around within an 18 mile radius (plus/minus) from where they lived. In a 2022 article (1), author Wade H. Mann discussed the distances and time people took to reach Point A to Point B. To paraphrase him, walking was the way most people used to travel, especially the poor, servants, and working people. Mann’s distances and times provide a quick perspective. For his extrapolations, he used the information he gleaned about the Bennet family in Pride and Prejudice, their walks to the village of Meryton, and the distance of Longbourn to London. In short order, he discussed:

- Lydia’s walks to Meryton nearly every day. (Distance: 1 mile each way.) One can assume that servants who worked for the Bennets also walked those distances, if not farther, to and from their homes every morning and evening after their shifts were over. One can also imagine servants, be they male or female, being sent on frequent missions of 1 mile or more throughout the day to obtain food or medicines, and to receive packages, or deliver letters with information for merchants and notes of appreciation or invitation to close neighbors.

(c) Dover Collections, Supplied by Art UK

- Elizabeth’s walk of three miles to visit Jane at Netherfield Park over wet fields was easy for her strong, athletic body. She would not have been “intimidated by a six-mile [round trip] walk.” If this was the case for a gentle woman of her status, one can imagine that male or female servants and field laborers would think nothing of walking six miles one way to work.

- In this bucolic image of a country road in Kent, painted in 1845 by William Richard Waters, three women are shown along a dirt road. (The village is located in the far horizon.) The woman on the left is probably a servant. From their dress, the two sitting females are gentle women taking a break. Although this painting was created past Austen’s day, rural villages were still relatively unchanged. With the advent of railroads and macadam roads, long distance travel became easier for those who could afford it, but long walks were still a part of daily life during the 19th century.

Distances in Regency England

As mentioned before, the distance between Longbourn, where the Bennets lived, and Netherfield Park, which Mr Bingley rented, was only three miles.

On a good surface, almost everyone walks 3 to 3.5 miles per hour; ordinary people can walk 10 to 24 miles per day. Twenty-four miles is the exact distance from Longbourn to Gracechurch Street [London], so even on foot, it’s only a hard day’s walk.” (1)

According to today’s estimates, the distance from London to Bath is approximately 115 miles (plus minus 30 miles depending on the roads one travels and which fields they chose to cross). Given the above estimate, and that, depending on their age and physical ability to walk from 10 to 24 miles per day, this journey would take a walker anywhere from 11½ to 4.8 days. In our fast-paced world, such a long time would be unacceptable. 250 years ago it was not. Travelers also minded their pocketbooks in terms of their budgets for lodging. Some might even need to find employment along the way.

London to Bath, google maps

Road surfaces and weather conditions mattered

If you’ve ever walked along a dirt path in a large park, you might have stumbled across fallen limbs and trees, climbed up and down steep paths, and treaded carefully over rocky surfaces, etc. Road conditions in and around most of England’s rural villages were abysmal until the early 19th century. Macadamized roads, with their crushed stone surfaces were constructed in 1815, just 2 years before Austen’s death. During most of her life, she would have largely known the miseries of walking along and riding on dirt roads that turned into muddy quagmires on rainy days.

Rains were frequent in this island country. Roads became so rutted that they were almost impassable in certain areas, where mud slowed horse drawn coaches and carriages, which forced riders and people to take down luggage and packages, and push the vehicles, or to walk to nearby shelters and villages. Mrs Hurst Dancing, a book that features Diana Sperling’s charming watercolours of her life during this time, shows how weather affected her family’s everyday lives.

This image shows the challenges of a muddy road with deep wagon tracks by a family embarked on an eleven mile walk. Seeing how these gentle folks struggled on an excursion of their choice, we can imagine the challenges many servants faced walking to their place of employment, having no other option.

A walk of 11 miles in deep mud, Mrs Hurst Dancing (2), P. 60 (Image, Vic Sanborn)

Walking to Dinner at a Neighbor’s House, Mrs Hurst Dancing (2) P38. (Image: The Jane Austen Centre)

Effects of weather

Frequent rains were not the only problem. Cold winters and deep snow provided unique challenges during the years known as The Little Ice Age (1811-20), when winters were harsher than normal. People who embarked on walking long distances needed to plan their routes in advance, which included knowing the condition of the roads (often through word of mouth or by previous experiences) and which villages could offer affordable shelters. Many itinerant laborers would have no problem sleeping in a farmer’s barn on a soft bed of hay in exchange for work.

Snow and ice made travel extremely difficult and was often avoided unless absolutely necessary. People would hunker down indoors and wait for the snow to clear before embarking on long journeys, as conditions could change rapidly. (My favorite Emma incident is when Mr Woodhouse, dining at the Weston’s house, INSISTED on leaving a dinner party immediately at the first signs of snowflakes. The Woodhouse party left, even though dinner had barely begun. Mr Woodhouse feared being stuck in snow. Austen knew her comedic settings well, but she was also knowledgeable about the realities of travel in her time.)

Detail of a Mail Coach in a snow drift with a Coachman leaving to seek assistance, James Pollard. To view the full painting and to read a complete description of the situation, click on this link to Artware Fine Art.

Itinerant laborers and sales people

Towns and villages were largely isolated. In cosmopolitan centers, like London, residents received the latest news almost as fast as Regency travel allowed. Thus cities and major metropolitan centers had more access to most of the benefits that a well informed society offered.

Villagers were often the last to know about the latest news about fashion, music, and dance. Enter the itinerant wanderers, the purveyors of knowledge and of all things current, albeit months past the time that the citizens of Paris and London knew about them.

Those with special talents profited the most from their peripatetic lives. A musician could offer entertainment with the latest popular ditties or teach lessons on an instrument, such as a piano forte or violin. A dance master might teach the latest steps from ‘The Continent’ that a young lady and gentleman should know.

The dancing master in the above image, was employed to teach children the steps and dance moves of the latest dances.

Talented and professional individuals – music teachers, dance instructors, tutors and the like – often had their services enlisted beforehand, and likely travelled by stage coach or on horseback to their destinations. They would stay in a nearby village or with the family that employed them for the duration of their contract before moving on.

Other people with various skills travelled between cities and towns either looking for work, or to sell their wares. They sold items as varied as kitchen equipment in town squares or brightly colored ribbons at county fairs. Some individuals crossed the English Channel, carrying fashion books and paper dolls* to inform the populace about the latest changes in fashions. I imagine farriers and blacksmiths were in hight demand, since horses were vital. Others offered seasonal labor in exchange for a meal or a place to sleep. Some were beggars or vagabonds who scrounged for any scraps.

The sad fact was that in a land of plenty, land enclosures took away the common fields from villagers by fencing off the shared, common lands, which were vital to rural folks by providing grazing land for livestock, and offering legal ways to gather firewood or hunt game. The impact of enclosures on commoners was enormous, as their independence was taken away. Many left their villages and homes, looking for work in cities and elsewhere, making their situation worse than before.

Beggar in early 19th C. London, John Thomas Smith, Spitalfields Life.His broom indicates that he might have been a street sweeper.

Itinerants also cadged free rides from friendly farmers and workers, or hitched a ride to the next town. They might take a seat in the back of a humble cart for a few miles, and then continue their walk. Again, a workman/woman might offer their menial services in return for a favor.

Below are images of a variety of itinerant travellers. The first was created by the incomparable Thomas Rowlandson, of whom I am an enormous admirer.

Aerostation out at Elbows ~

or the Itinerant Aeronaut

Behold an Hero comely tall and fair!

His only Food. Phlogisticated Air!

Now on the Wings of Mighty Winds he rides!

Now torn thro’ Hedges!–Dashed in Oceans tides!

Now drooping roams about from Town to Town

Collecting Pence t’inflate his poor balloon,

Pity the Wight and something to him give,

To purchase Gas to keep his Frame alive. ~

The above copyright free image by Thomas Rowlandson is called Aerostation out at Elbows, or The Itinerant Aeronaut, 1785, Met Museum. The poem below the image is about Vincent Lunardi, an Italian balloonist, whose successful balloon ride was of short duration. Sadly he died in poverty.

Wandering musicians during the Georgian era were also known as gleemen.

Detail of street musicians in London surrounded by a crowd, Thomas Rowlandson.

A ballad singer

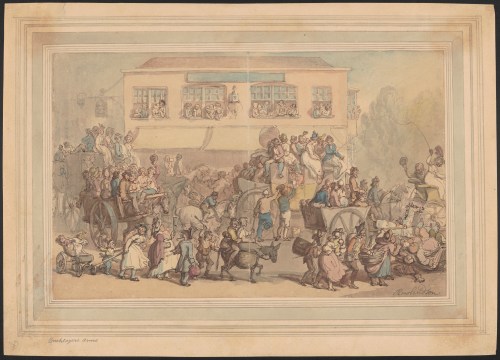

Wagons and carts for the common folk

Unlike the fancy carriages and equipages of the well heeled, conveyances for the lower classes were ordinary wagons, rough hewn carts, drays, wheelbarrows, wagonettes, pushcarts, donkey or pony carts, and the like.

This link to a Thomas Rowlandson image of country carts (1810) shows ordinary country folk setting out on a journey. These are a few details of that image:

Setting out behind the covered wagon

Loading the wagon

Larger covered wagons were also used for longer distances. This wagon, to my way of thinking, is the poor man’s stage coach.

Rowlandson, Flying Wagon, 1816, MET Museum, public domain

In Mr. Rowlandson’s England, Robert Southey described the laboriously slow progress of a flying wagon:

The English mode of travelling is excellently adapted for every thing, except for seeing the country…We met a stage-waggon, the vehicle in which baggage is transported, I could not imagine what this could be; a huge carriage upon four wheels of prodigious breadth, very wide and very long, and arched over with a cloth like a bower, at a considerable height: this monstrous machine was drawn by six large horses, whose neck-bells were heard far off as they approached; the carrier walked beside them, with a long whip upon his shoulder…these waggons are day and night upon their way, and are oddly enough called flying waggons, though of all machines they travel the slowest, slower than even a travelling funeral.” – P 23

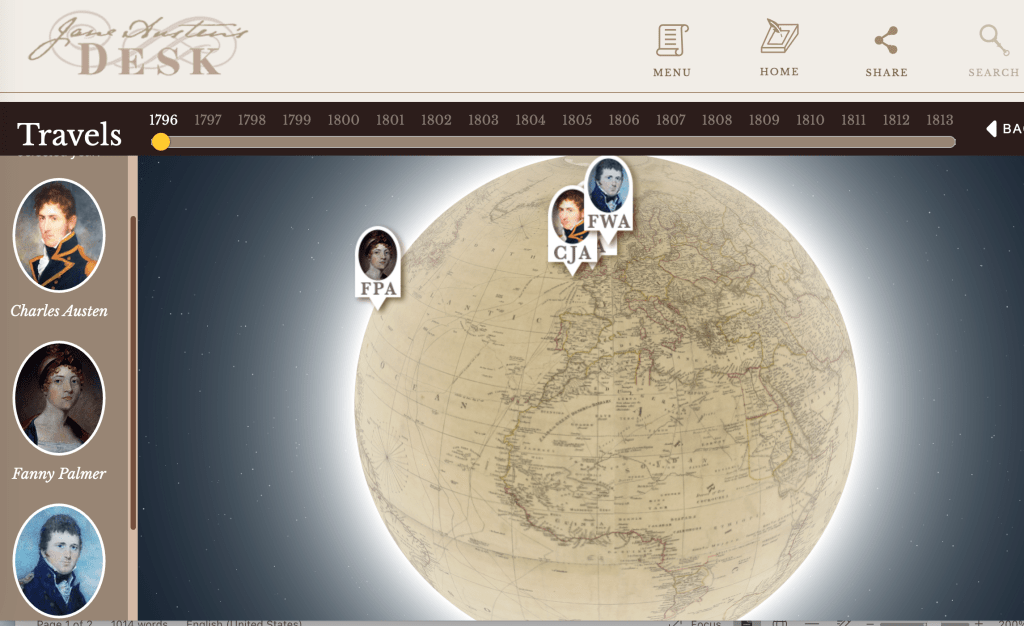

Thomas Rowlandson, Country Folk Leaving for the Town, 1818

Take a peek inside this link to Meisterdrucke.us of Thomas Rowlandson’s cartoon ‘Depicting Country Folk Leaving for the Town’. It’s a joyous event, with all the people setting off to…where? A country fair perhaps? The procession is obviously as slow as the Flying Wagon, for many people are walking in pairs and carrying baskets (Food for personal consumption? Produce or goods for sale or barter?).

Lastly, this image by Rowlandson of a cart carrying a dead horse to the knacker is sad in several respects. Not only has the family lost a valuable animal, but, looking at the faces of the parents, much of their livelihood as well. One can’t imagine that they can afford to purchase another horse any time soon.

Bricklayers Arms, an image by Thomas Rowlandson, sums up the variety of wagons and methods of transportation.

Stage Coaches

These coaches were unattainable for the very poor, but the working classes could afford an uncomfortable spot on an exposed space ‘up top’.

A Laden Stage Coach Outside a Posting Inn

Thomas Rowlandson, Stage Coach, 1787, Met Museum, Public Domain

Given the road conditions, ‘up top’ could be a dangerous choice, as one of the images below shows. Newspaper clippings of the time mentioned the deaths of passengers thrown violently to the ground when a stage coach was involved in an accident.

Should everything go right on the journey, and the coach stops at a coaching inn, the unfortunate individuals ‘up top’ are then …”directed to the kitchen with the pedestrians, gypsies, itinerant labourers and soldiers. Do not expect help getting off the eight foot high coach; if you were a lady, you would not be on top in the first place, would you?” A Guide to the Georgian Coaching Inn

Transportation across water

Travellers faced many impediments as they progressed along rural roads, a major one being water. While larger cities and towns provided bridges, most villages surrounded by country lanes did not have this luxury. Passage over small streams was possible – large rocks were frequently placed at comfortable intervals to make walking easier.

Methods of transportation across a wide and deeper stream or river included a ferry, or a pulley and rope system to tow a wood platform from one bank to the other. (3)

Barges pulled by horses and mules along towpaths provided inner- and inter-city travel along a system of interconnected canals, which sped the movement of people and goods.

“A horse, towing a boat with a rope from the towpath, could pull fifty times as much cargo as it could pull in a cart or wagon on roads. In the early days of the Canal Age, from about 1740, all boats and barges were towed by horse, mule, hinny, pony or sometimes a pair of donkeys.” Wikipedia, Horse-drawn boat

As mentioned, ferries, canal boats, and barges carried heavier loads. These boats also provided accessibility and affordability to a variety of people from different classes.

Sources:

(1) Distance and Time In Regency England, By Wade H. Mann, author of A Most Excellent Understanding, Q&Q Publishing, Jun 8, 2022

(2) Mrs Hurst Dancing, To find more images by Diana Sperling, click on this page to the Jane Austen Centre.

(3) Ferrymen and water men: Water Transportation and Moving in Regency England

Not quite related to this topic, but equally as fascinating are:

Read Full Post »