Gentle Readers, Frequent contributor Patty from Brandy Parfums recently attended a cooking class that featured classic recipes. She says of her experience: “When we think about our wonderful holiday dinners coming up, it is good to remember the origins of mid-winter celebrations, so ingrained in our DNA.” I can’t think of two more interesting recipes to try than the two Patty describes in this post.

Gentle Readers, Frequent contributor Patty from Brandy Parfums recently attended a cooking class that featured classic recipes. She says of her experience: “When we think about our wonderful holiday dinners coming up, it is good to remember the origins of mid-winter celebrations, so ingrained in our DNA.” I can’t think of two more interesting recipes to try than the two Patty describes in this post.

Cooking Class Taught by Culinary Historian Cathy Kaufman at I.C.E, the Institute of Culinary Education, New York, NY on December 5, 2011 by Patricia Saffran

Before there was Christmastime, the cherished holiday and lovely dinner that many have come to look forward to each winter, in ancient times there was the winter solstice celebration of rebirth focusing on the sun, in Stonehenge and other Neolithic sites. Later, light-starved Romans celebrated the Saturnalia, in 217 BC starting with December 17th and extending to a week long festival with gorging and other very pagan activities.

Then there was the Roman and Mithra Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, the birthday of the invincible sun, December 25th. Old customs die hard but we still pay tribute to tree worship in the form of the Christmas tree, that came to Great Britain from Germany. It was first introduced by Queen Charlotte, with the connection made stronger later by Prince Albert. When we come to Victorian times is when the present traditions take hold.

As culinary historian, Cathy Kaufman described the holiday’s traditions and her special class:

“Nothing pushes the nostalgia button at Christmastime more than Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, with its warming images of a candlelit tree and Victorian plenitude. Yet prior to the 19th century, Christmas was a very different holiday, and it was only in the Victorian era that our concept of Christmas as a child-centered family holiday arose. After reviewing the evolution of Christmas holidays, we will use 19th-century English cookbooks, such as Charles Francatelli’s The Modern Cook and Eliza Acton’s Modern Cookery for Private Families, to create a groaning board of Victorian delights, including Jerusalem Artichoke Soup; Lobster Fricassée; Baked Goose with Chestnuts; Roasted Filet of Beef à l’Anglaise; Endives with Cream; Christmas Pudding; Gingerbread; and Twelfth Night Cake.”

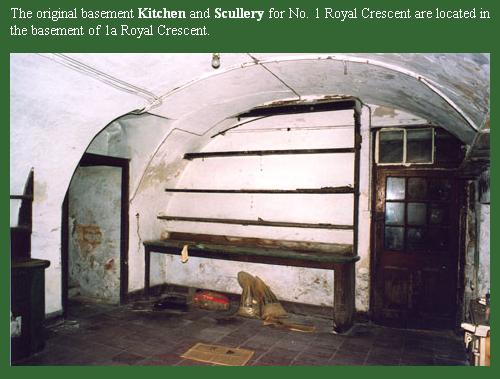

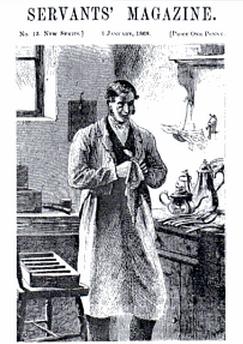

Cathy continued, “This is upper class food that we’re making tonight, that took a large staff in the kitchen to prepare, with no expenses spared, using the most luxurious ingredients. It’s also infusion cuisine made with expensive stocks, showing the French influence in this period. There’s also a fair amount of cream in many dishes with a touch of cayenne pepper, an influence of the British colonials in India. The French at this time would have just used nutmeg. There were many women cooks in the kitchens of the wealthy in England, and in France there were more men in the kitchens.”

We separated into three groups to make the various dishes. I chose the group that was making the Charles Francatelli recipe for Beef à l’Anglaise. Francatelli was born in London in 1805 and went on to study with the great chef Marie-Antoine Carême in France, inventor of haute-cuisine. (At the downfall of Napoleon, Carême later went to work in London for the Prince Regent and George IV.) Francatelli was the chef for Queen Victoria and went on to be the chef at the Reform Club. His influential book was called The Modern Cook, published in 1846. This recipe is very time consuming and labor intensive with a vegetable and olive oil marinade and Financière and Espagnole (including truffle juice and veal stock) sauces for basting and serving. Our group also made vegetable garnishes and one of the three desserts, the Plum Pudding.

Another group made the Lobster Fricassée from an Eliza Acton recipe. Eliza Acton was born in Sussex in 1799. Like Francatelli, she spent time in France. She is credited with writing the first practical cookbook with a list of ingredients and instructions. Mrs. Beeton was supposed to have modeled her cookbook on Acton’s. The lobster recipe is somewhat complicated in that uses both a Béchamel and Consommé made from veal, mushrooms, ham, vegetables and stock. Final baking in the oven with the sauce and bread crumbs finished off this delectable dish.

The goose recipe from Charles Francatelli featured a Madeira wine mirepoix and a luting paste, a flour and water cover for the goose’s first hour of cooking to keep it moist.

Here are two recipes that are absolutely delicious and will be easy to make for a home version of a Victorian Christmas feast. Both recipes are presented in the original text and then in Cathy Kaufman’s modernized version for today’s kitchens.

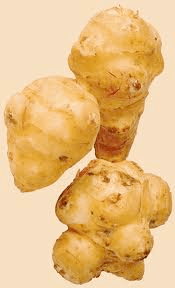

Jerusalem Artichoke, or Palestine Soup (Eliza Acton)

Wash and pare quickly some freshly dug artichokes, and to preserve their colour, throw them into spring water as they are done, but do not let them remain in it after all are ready. Boil three pounds of them in water for ten minutes; lift them out, and slice them into three pints of boiling stock; when they have stewed gently in this from fifteen to twenty minutes, press them with the soup, through a fine sieve, and put the whole into a clean saucepan with a pint and a half more of stock; add sufficient salt and cayenne to season it, skim it well, and after it has simmered two or three minutes, stir it to a pint of rich boiling cream. Serve it immediately.

2 lb. Jerusalem artichokes

4 cups chicken stock

Salt and freshly ground white pepper to taste

1/8 teaspoon cayenne pepper, or more to taste

5/8 cup heavy cream mixed with 1/4 cup Crème fraîche

Pare the Jerusalem artichokes. Drop the pared Jerusalem artichokes into a pan of boiling salted water. Cook for ten minutes to set the color. Drain and refresh.

Slice the Jerusalem artichokes into pieces of about 1/2 inch thick and place in a saucepan with the chicken stock. Simmer for 20 minutes and pass mixture through a food mill three times [or puree in a blender].

Return the puree to a clean saucepan and add the spices and heavy cream mixture. Cook for two minutes, skim any impurities off the surface, adjust the seasoning and serve.

Fronticepiece, Modern Cookery by Eliza Acton

Gingerbread (Eliza Acton)

Whisk four strained or well-cleared eggs to the lightest possible froth (French eggs, if really sweet, will answer for the purpose), and pour to them, by degrees, a pound and a quarter of treacle, still beating them lightly. Add, in the same manner, six ounces pale brown sugar, free from lumps, one pound of sifted flour, and six ounces of good butter, just sufficiently warmed to be liquid, and no more, for if hot, it would render the cake; it should be poured in small portions to the mixture, which should be well beaten up with the back of a wooden spoon as each portion is thrown in: the success of this cake depends almost entirely on this part of the process. When properly mingled with the mass, the butter will not be perceptible on the surface; and if the cake be kept light by constant whisking, large bubbles will appear in it to the last. When it is so far ready, add to it one ounce of Jamaica ginger and a large teaspoonful of cloves in fine powder, with the lightly grated rinds of two fresh, full-sized lemons. Butter thickly, in every part, a shallow square tin pan, and bake the gingerbread slowly for nearly or quite an hour in a gentle oven. Let it cool a little before it is turned out, and set it on its edge until cold, supporting it, if needful, against a large jar or bowl. We have usually had it baked in an American oven, in a tin less than 2 inches deep; and it has been excellent. We retain the name given to it originally in our circle.

Please note: The treacle, sugar and flour are measured by weight, not by volume.

2 tablespoons softened butter for preparing the baking pans

3 eggs

20 oz treacle

6 oz light brown sugar

6 oz butter, melted and cooled

16 oz cake flour, sifted

4 tablespoons ground ginger

1 teaspoon ground cloves

grated zest of two lemons

Preheat the oven to 350ー F. Generously rub the inside of a 9 x 9 x 2 baking pan with the softened butter and set aside.

Stir the eggs together and pass them through a strainer to remove the white threads holding the yolks. Transfer to the bowl of a standing mixer fitted with the whisk attachment and beat for two minutes. Very slowly pour in the treacle, beating constantly. Add the brown sugar in a slow trickle and continue beating. Add the butter and a steady stream, beating thoroughly to incorporate. Add flour in several additions, continuing to whisk. Finally, whisk in the spices and the lemon zest.

Pour the batter into the prepared pan and bake for 50 minutes to an hour, or until baked through. Cool on a rack before unmolding. Dust with confectioners’ sugar before serving.

Links:

- Culinary Historians, NY

- Historictable

- Culinary Arts

- The Institute of Culinary Education

- The Cook’s Guide and Housekeeper’s and Butler’s Assistant, Francatelli

- The Philosophies and Religions of the Roman Empire